There’s a certain kind of weariness that permeates some films from the 80s, a grit beneath the neon glow that speaks less of glamorous excess and more of desperation. You feel it clinging to the celluloid of 1986's Heat, a film carrying the weight of expectation thanks to its star, Burt Reynolds, and its legendary screenwriter, William Goldman, yet arriving on video store shelves with a troubled history already whispering around its edges. It wasn’t the breezy action romp some might have anticipated from a Reynolds vehicle set in Vegas; instead, it offered something murkier, more bruised, reflecting perhaps the very difficulties that plagued its creation.

Neon Nights and Last Resorts

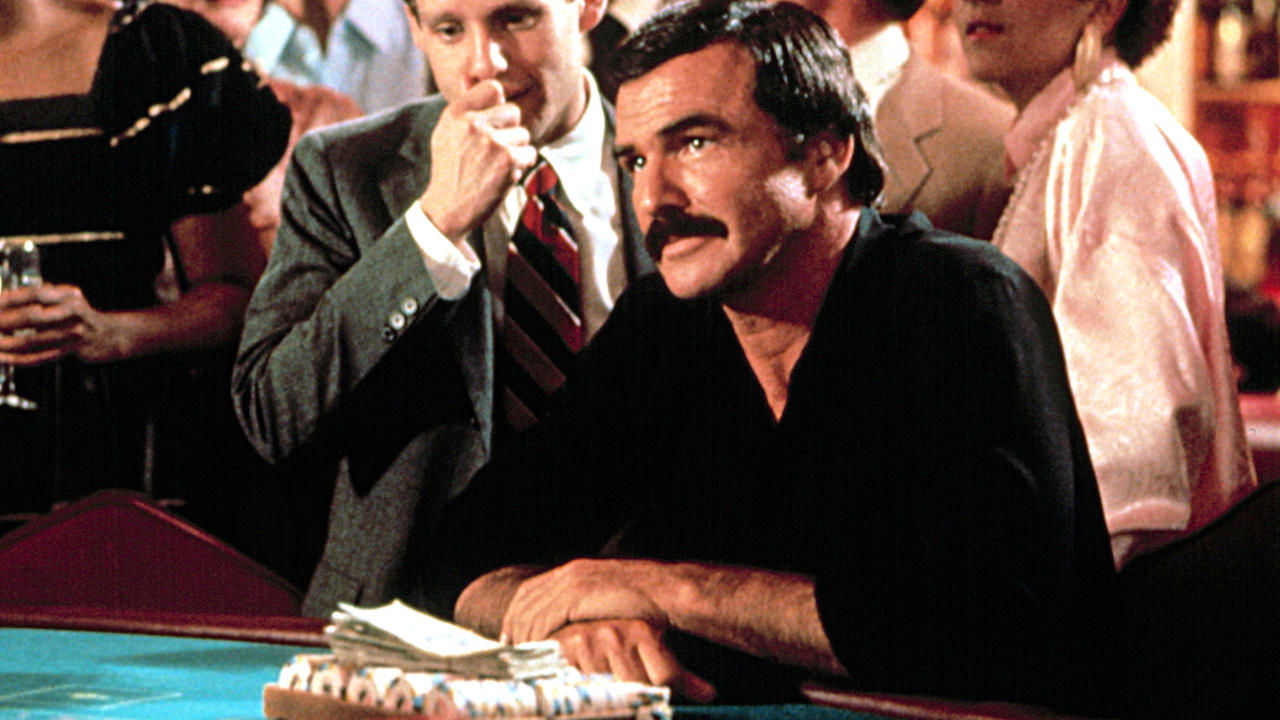

The premise, adapted by Goldman (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Marathon Man) from his own novel, is classic noir territory transposed to the shimmering, unforgiving landscape of 80s Las Vegas. Nick 'Mex' Escalante (Reynolds) is a man trying to leave his past behind – specifically, a crippling gambling addiction. He scrapes by doing odd jobs, "chaperoning" tourists and offering protection, dreaming of saving enough ($25,000, a specific, almost talismanic figure) to escape to Venice, Italy. But Vegas has claws. When his friend and occasional employer, Holly (Karen Young), is brutally assaulted by a connected slimeball named Danny DeMarco (Peter MacNicol), Mex finds himself pulled back into the violent undertow he tried so hard to swim away from.

It’s a setup ripe with potential, promising a blend of tough-guy action and character study. And indeed, the film captures a certain down-at-heel Vegas atmosphere – not the high-roller suites, but the dusty backrooms, the cheap diners, the palpable sense of lives lived on the edge of ruin. You can almost smell the stale cigarette smoke and cheap whiskey clinging to the screen.

A Star Dimmed, A Production Fractured

Central to the film, of course, is Burt Reynolds. But this isn't the grinning, fast-talking Bandit many fans might recall. Reynolds had suffered a severely broken jaw during a stunt mishap on the set of City Heat (1984) a couple of years prior, leading to significant weight loss and chronic pain during the filming of Heat. The physical toll is visible. His usual kinetic energy feels banked, replaced by a heavy-lidded exhaustion. While arguably diminishing his typical screen charisma, this unintended physical vulnerability lends Mex an unexpected layer of fragility. He moves like a man carrying invisible burdens, his moments of explosive violence feeling less like heroic prowess and more like desperate acts from someone pushed too far. Does it entirely work? That’s debatable. At times, he seems simply tired, the performance lacking its usual spark. Yet, in others, this subdued quality resonates with Mex's internal struggle against his own destructive impulses.

This wasn't the only shadow hanging over the production. Initial director Dick Richards (Farewell, My Lovely) clashed intensely with Reynolds, culminating in an alleged altercation that saw Richards exit the project. Veteran director Jerry Jameson (Airport '77) stepped in uncredited to complete the film. Such turmoil rarely benefits the final product, and you can sense a certain unevenness in tone, a feeling that the film isn't quite sure if it wants to be a gritty character piece or a straightforward revenge thriller. Adding another layer of intrigue, William Goldman himself publicly disowned the final film, famously lamenting the changes made to his script and adaptation. It's a classic case of "what might have been." Considering Goldman's pedigree, one wonders what version existed on the page before the compromises and conflicts took their toll. Reportedly, the film only recouped about $2.8 million at the box office, a stark failure given the names involved.

Unexpected Menace and Lingering Questions

Despite the troubles, there are elements that stand out. Karen Young, as Holly, provides a grounded emotional anchor, her trauma feeling real and her desire for retribution understandable. But the film’s most electrifying jolt comes from an unlikely source: Peter MacNicol. Known often for quirky, gentle characters (think Janosz Poha in Ghostbusters II (1989) or Stingo in Sophie's Choice (1982)), MacNicol here is genuinely unsettling as the sadistic, entitled mob scion DeMarco. His slight frame and seemingly boyish features mask a chilling capacity for cruelty, making him a far more memorable villain than a more physically imposing actor might have been. His confrontations with Reynolds crackle with a strange energy, the contrast between Mex's world-weariness and DeMarco's arrogant depravity proving surprisingly effective.

The action sequences themselves are brutal and functional, leaning more towards sudden bursts of violence than elaborately choreographed set pieces. Mex’s preferred weapons are often improvised or bladed, adding a visceral, up-close nastiness that fits the film’s generally grim outlook. There’s little glamour here, even when Mex inevitably goes on the offensive.

VHS Shelf Life

So, where does Heat (1986) sit in the pantheon of 80s video store staples? It’s certainly not a forgotten masterpiece, nor is it simply dismissible. It’s a fascinating artifact – a confluence of major talent grappling with difficult circumstances, resulting in a film that feels bruised and compromised, yet retains flashes of what could have been. It’s a mood piece as much as an action film, steeped in a particular kind of weary, sun-baked despair. Watching it today feels like uncovering a slightly damaged curio, interesting more for its backstory and its handful of strong moments (particularly MacNicol’s chilling turn) than for its overall coherence. I remember picking up the distinctive VHS box, drawn by Reynolds' name, and finding something darker and stranger than expected.

Rating: 5.5/10

The score reflects a film hampered by its troubled production and Reynolds' compromised state, preventing it from reaching the potential inherent in Goldman's source material and some strong supporting performances. It’s uneven and often sluggish, yet holds interest due to MacNicol’s villainy, the palpable 80s Vegas grime, and the curiosity factor surrounding its creation.

Heat remains a compelling watch for Reynolds completists and fans of gritty 80s thrillers, less for its triumphs and more as a cinematic puzzle – what pieces were lost, and what ghosts of a better film flicker within its frames?