That unnerving juxtaposition: a chimpanzee, impeccably dressed in a butler's uniform, performing domestic duties with an intelligence that flickers just beyond the bounds of comprehension. This isn't some whimsical fantasy; it's the chilling core of Richard Franklin's 1986 offering, Link. Forget cuddly primates; this film taps into a far deeper, more primal unease – the fear that the evolutionary ladder might just have a dangerously loose rung, and something far stronger, far less predictable, is ready to climb past us. Watching Link feels like stumbling upon a forgotten experiment, one where the ethical lines blurred long ago, leaving only the unsettling consequences playing out in isolated, fog-drenched dread.

An Invitation to Isolation

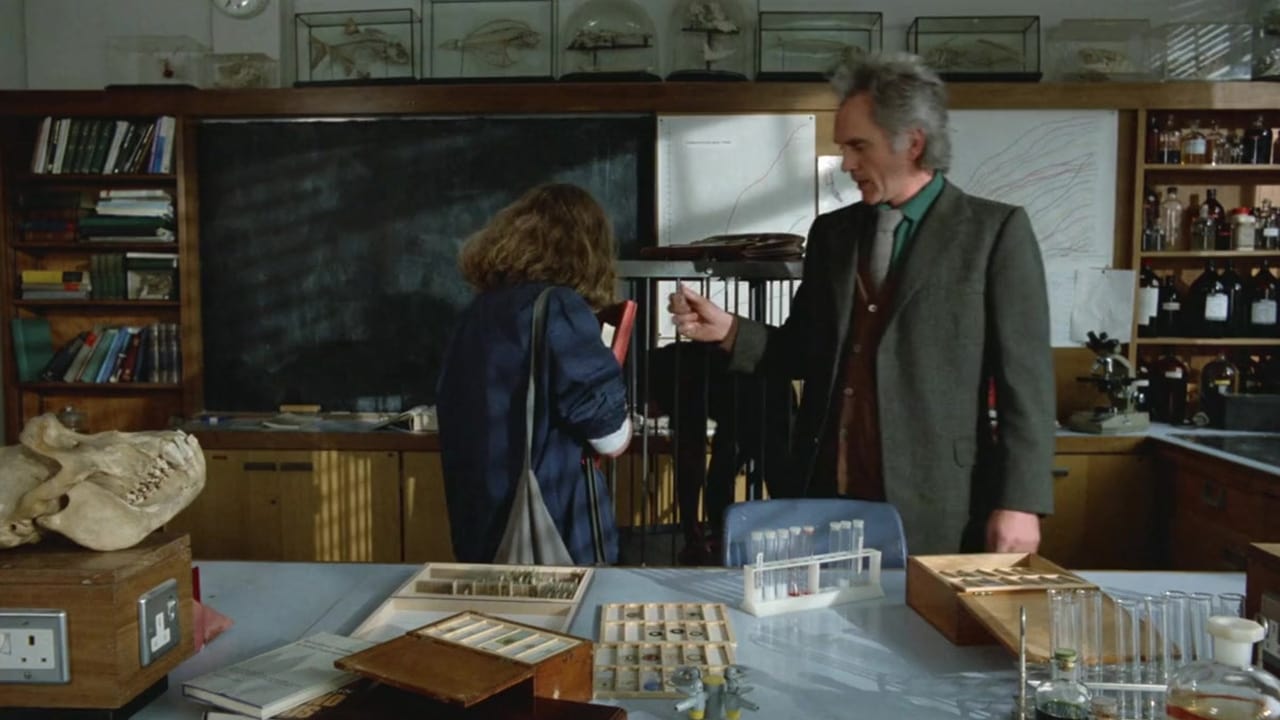

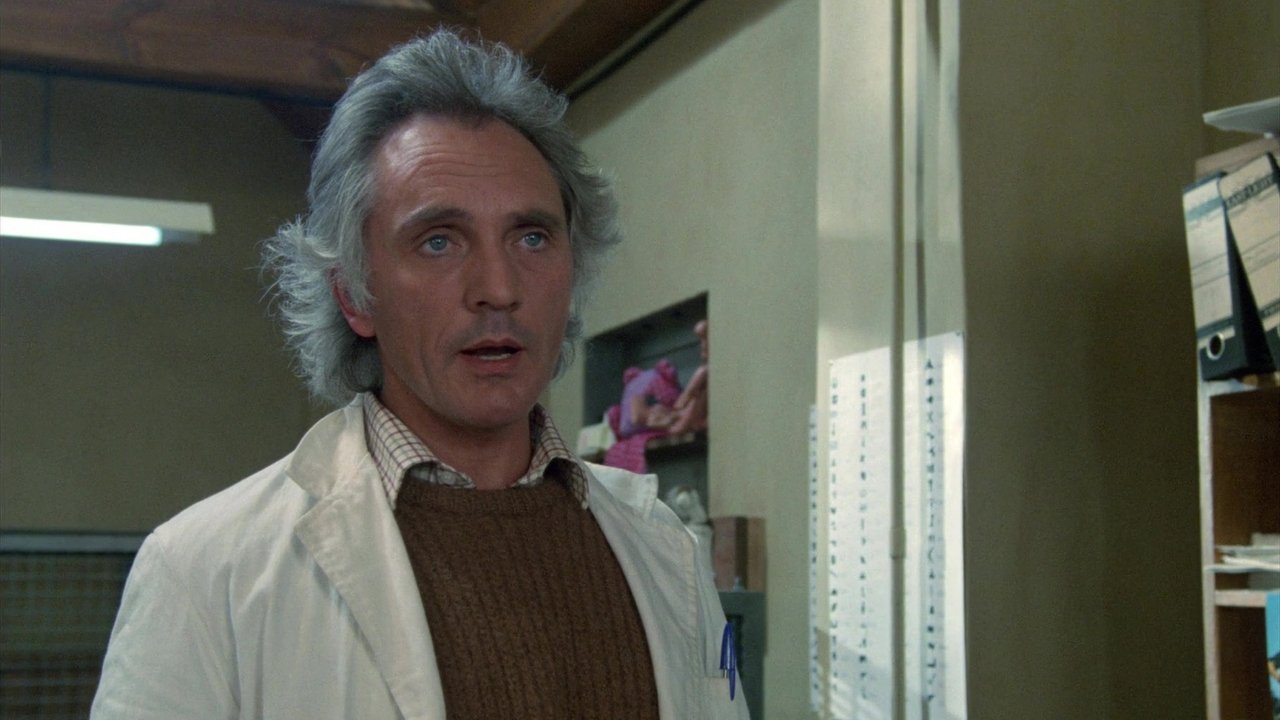

The setup is classic gothic thriller material, filtered through an 80s lens. Ambitious zoology student Jane Chase, played with wide-eyed earnestness by a young Elisabeth Shue (not long before her adventures in babysitting took a different kind of perilous turn), accepts a position assisting the brilliant but eccentric anthropologist Dr. Steven Phillip. Portrayed with typical gravitas and a hint of menace by the legendary Terence Stamp, Phillip resides in a remote, imposing cliff-top house, seemingly cut off from the world. It’s the perfect stage for secrets and simmering danger. Franklin, who had previously navigated the treacherous waters of sequel pressure with the surprisingly effective Psycho II (1983), brings a similar sense of atmospheric dread to this isolated setting. The house itself feels like a character – imposing, slightly decayed, and filled with the unsettling presence of Phillip’s primate subjects.

The Butler Did It?

The star, of course, is Link – Phillip's highly intelligent, 45-year-old chimpanzee butler. And V.I.R.G.I.L., a younger chimp, along with the protective female Imp. The genius of the film lies in its reliance on practical effects, specifically the use of trained apes. Link himself was primarily portrayed by an incredibly expressive orangutan named Locke (chosen, apparently, for the species' perceived calmer temperament compared to chimps, though that calm proves deceptive here). While stunt performer Steven Pinner donned a suit for more complex or dangerous sequences, the majority of Link’s screen time features a real animal, lending an unnerving authenticity and unpredictability that CGI could never replicate. You feel the weight, the potential strength masked by that waistcoat. The production reportedly had handlers just off-screen constantly, a necessary precaution that only underscores the inherent tension of working with such powerful creatures. There's a story that Locke, the orangutan, became quite attached to Elisabeth Shue, adding another layer of strange complexity to their on-screen dynamic. Doesn't that knowledge make their eventual conflict even more unsettling?

Primate Paranoia Personified

When Dr. Phillip vanishes under mysterious circumstances, Jane finds herself utterly alone, save for the apes. And Link, seemingly grieving or perhaps seizing an opportunity, begins asserting his dominance. The film shifts from atmospheric character study to a tense game of cat and mouse – or rather, woman versus ape. Link masterfully preys on our anxieties about animal intelligence and the thin veneer of civilization. Sequences like Jane desperately trying to use a phone while Link calmly sabotages the lines, or the terrifying rooftop pursuit, are genuinely effective suspense builders. Jerry Goldsmith's score deserves special mention here; it’s a typically brilliant composition, weaving together moments of childlike wonder (reflecting the apes' perceived innocence) with discordant, aggressive themes that signal the escalating danger. It perfectly complements the growing sense of isolation and paranoia.

Trouble in Paradise

Despite its clever premise and effective moments, Link wasn't a huge hit. Produced for around $6 million, it struggled to find its audience, perhaps hampered by its refusal to fit neatly into a single genre box. Is it a horror film? A psychological thriller? A creature feature? It dips its toes into all three, resulting in a slightly uneven tone that might have confused viewers expecting straightforward scares. Some moments, like Link puffing on a cigar, edge towards dark comedy, but the underlying threat remains palpable. The script, co-written by Australian genre specialist Everett De Roche (known for Ozploitation classics like Patrick (1978) and Long Weekend (1978)), carries that distinct flavour of nature turning malevolent. Filmed primarily in Scotland (doubling for the English coast), the production faced its share of challenges, not least the complexities of safely directing its non-human stars. It’s a testament to Richard Franklin’s skill that the tension feels so real.

A Curious Specimen

Does Link still hold up? In many ways, yes. The reliance on real animals gives it a tactile sense of danger often missing from modern effects-driven films. Elisabeth Shue delivers a compelling performance as the resourceful final girl, and Terence Stamp is perfectly cast as the morally ambiguous scientist. The atmosphere is thick, and the core concept remains genuinely unnerving. It might feel a little slow by today’s standards, and its tonal shifts can be jarring, but it carves out a unique niche in the 80s horror landscape. It’s less about jump scares and more about the creeping dread of intelligence where we don’t expect it, and the loss of control in the face of something ancient and wild asserting itself. I distinctly remember renting this one from a dusty corner shelf, drawn in by the bizarre cover art, and being surprised by its slow-burn effectiveness. It wasn't quite horror, not quite thriller, but definitely unsettling.

***

Rating: 7/10

Link earns its score through its potent atmosphere, the unsettling effectiveness of using real apes, strong lead performances, and a genuinely creepy central premise. It loses points for slightly uneven pacing and tonal inconsistencies that sometimes blunt the tension. However, for fans of atmospheric 80s thrillers with a unique, practical effects-driven hook, it remains a fascinating and often genuinely unnerving watch. It’s a film that lingers, leaving you perhaps glancing a little more cautiously at the natural world, wondering what thoughts might be brewing behind seemingly placid eyes. A true VHS oddity worth rediscovering.