Before Pedro Almodóvar became the globally celebrated, Oscar-winning auteur synonymous with vibrant melodrama and intricate human portraits, there was Matador (1986). Finding this one on the video store shelf back in the day felt like stumbling upon something illicit, almost dangerous. Its stark, stylized cover art hinted at passions that didn't quite align with the usual Hollywood fare, and slipping that tape into the VCR confirmed it. Matador was, and remains, a film pulsing with a strange, feverish energy – a challenging, often unsettling exploration of obsession that burrowed under your skin.

### The Dance of Death and Desire

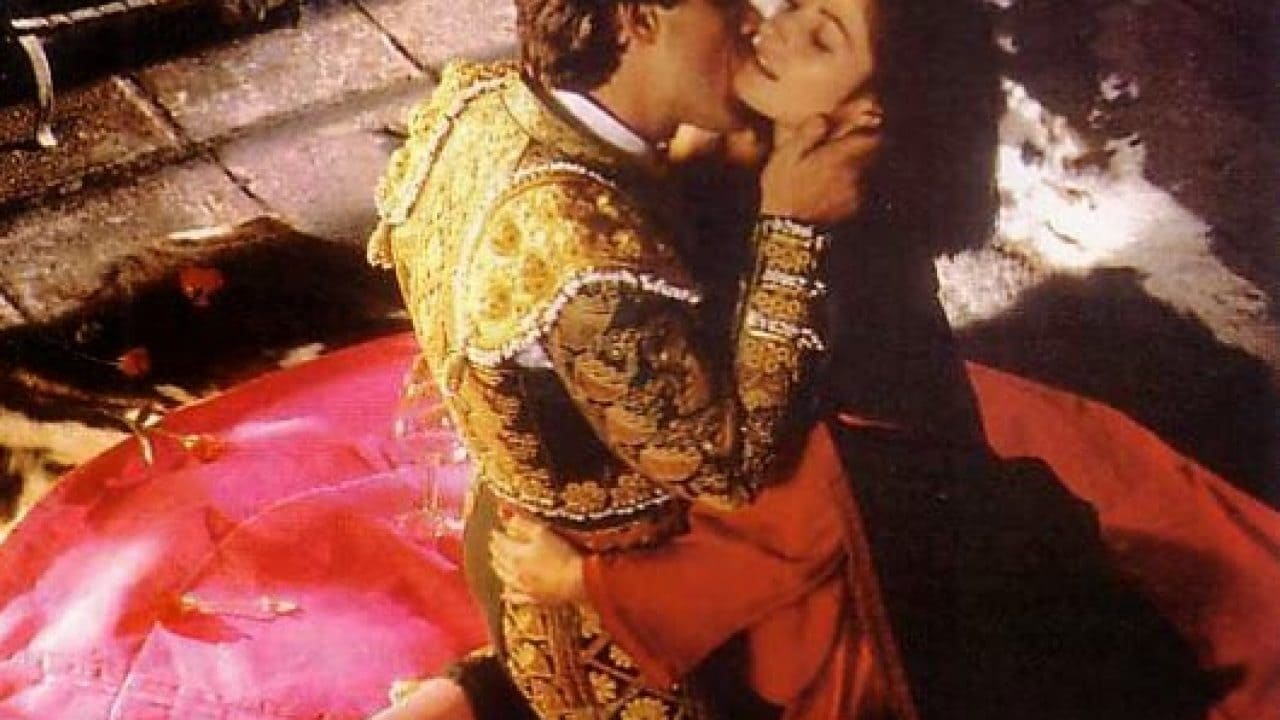

At its heart, Matador is about a connection forged in the darkest corners of human desire. Diego Montes (Nacho Martínez) is a former star bullfighter, forced into retirement by injury, now teaching the art of the kill. María Cardenal (Assumpta Serna) is a criminal lawyer with a chilling secret: she finds ultimate sexual release only at the moment of taking a life. Their paths intertwine, drawn together by a shared, macabre obsession that conflates the ecstasy of orgasm with the finality of death. It’s a premise that Almodóvar, co-writing with Jesús Ferrero, pushes to its provocative limits, creating an atmosphere thick with unspoken longing and fatalistic certainty. Remember how some films just felt different, heavier, sitting there on the rental shelf? This was definitely one of them.

### A Glimpse of Future Stardom

Caught in their deadly orbit is Ángel, played by a startlingly young Antonio Banderas in one of his early, crucial collaborations with Almodóvar. Ángel is one of Diego's students, a deeply troubled young man wrestling with religious guilt, psychic visions (or are they?), and burgeoning homosexual desires. His character is a fascinating pressure cooker of repression and confusion, falsely confessing to murders he couldn't have committed, driven by forces he barely understands. Watching Banderas here, years before Hollywood stardom in films like Desperado (1995), is captivating. You see the raw intensity, the vulnerability, and the willingness to dive into complex, uncomfortable territory that would define much of his best work. It’s a performance that feels both fragile and volatile, a perfect counterpoint to the icy certainty of Martínez and Serna. Almodóvar himself has sometimes seemed ambivalent about Matador in retrospect, occasionally citing script issues or feeling the central conceit was perhaps too abstract, but Banderas's anguished portrayal remains a powerful anchor.

### Saturated Style, Unflinching Vision

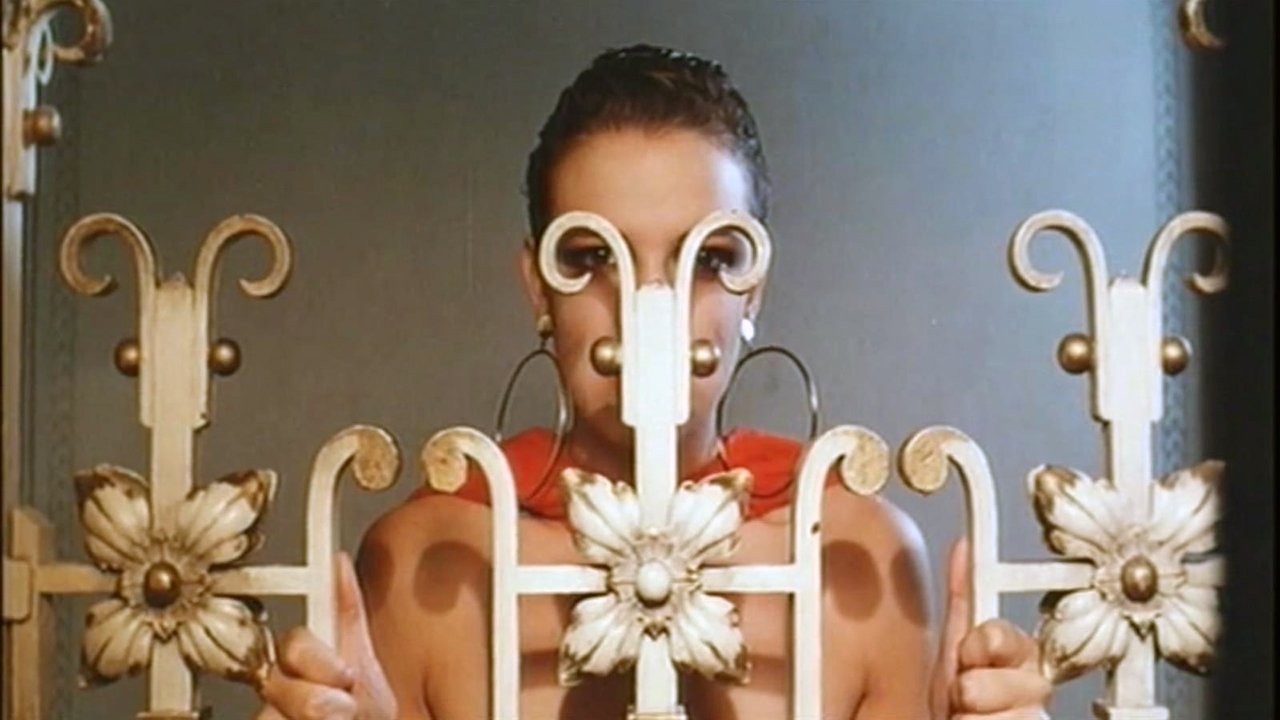

Even in this earlier phase of his career, Almodóvar's signature style is undeniable. The film explodes with bold colours – vivid reds dominate, naturally – and a heightened sense of melodrama that borders on the operatic. Yet, it’s fused with the structure of a thriller, albeit one more interested in psychological states than conventional suspense. The cinematography often frames characters in isolation, even when they share the screen, emphasizing their internal worlds. The score, too, adds to the pervasive sense of dread and fatal attraction. This wasn't just telling a story; it felt like Almodóvar was painting with emotion, using the visual language of cinema to express ideas that words alone couldn't capture. It's a far cry from the polished restraint of some of his later masterpieces, like Talk to Her (2002), possessing instead a raw, almost untamed quality.

### Confronting the Taboo

Let's be frank: Matador is not an easy watch. Its central theme – the eroticization of killing – is inherently disturbing. Almodóvar doesn't shy away from the implications, presenting the fatal encounters with a chilling directness that could feel shocking, especially discovered amidst the more mainstream action and comedy VHS tapes of the era. Was the film controversial? Absolutely. It dives headfirst into territory many filmmakers would avoid, exploring the most extreme intersections of Eros (love/desire) and Thanatos (death). Does it succeed entirely? That's debatable. The plotting can feel a little schematic, the characters driven more by thematic necessity than deep psychological realism at times. Yet, there's an undeniable power in its audacity, in its refusal to look away.

### The Weight of Performance

What elevates Matador beyond mere provocation are the central performances. Nacho Martínez as Diego exudes a weary charisma, the predatory stillness of a matador even in retirement. His obsession feels chillingly authentic. Assumpta Serna, as María, is magnetic. She portrays María’s lethal compulsion not as monstrous, but as an intrinsic, inescapable part of her being, conveying a strange mix of detachment and fervent desire. Their scenes together have a palpable, dangerous chemistry; they are two predators recognizing each other, circling towards an inevitable, shared destiny. Even within the film's heightened reality, their conviction lends a strange gravity to the proceedings.

Rating: 7/10

Matador earns a solid 7. It's a vital piece of Almodóvar's early filmography, showcasing his burgeoning talent, unique thematic concerns, and willingness to provoke. The performances, particularly from Serna and the young Banderas, are compelling, and the film possesses a potent, unsettling atmosphere that lingers. However, its challenging subject matter and occasionally schematic plotting might make it less universally accessible than his later works, and Almodóvar's own slight reservations about its cohesion feel somewhat justified. It lacks the emotional nuance and intricate character work of his peak films, leaning more heavily on its shocking central conceit.

For the adventurous viewer digging through the metaphorical VHS crates of cinema history, Matador remains a fascinating, darkly glittering artifact – a raw, sometimes uncomfortable, but undeniably potent early strike from a master filmmaker finding his voice amidst the shadows. It leaves you pondering the outer limits of passion and the darkness that can lie beneath the most civilized surfaces.