It starts with sunshine, doesn't it? That comfortable, almost deceptively placid rhythm of suburban life. Long Beach, California. Jimmie Rainwood, an airline mechanic played by Tom Selleck, living a good life – loving wife, stable job, the kind of everyday happiness that feels both attainable and fragile. Watching An Innocent Man (1989) again, that initial warmth feels almost like a setup, a deliberate lulling before the sudden, brutal plunge into darkness. It’s a film that asks a stark question right from the jump: how quickly can a normal life be utterly destroyed by forces beyond your control?

The Shattering of Normalcy

The premise is chillingly straightforward: mistaken identity leads two corrupt narcotics detectives, Mike Parnell (David Rasche, perfectly slimy) and Danny Scalise (Richard Young), to burst into Rainwood’s home, guns blazing. In the ensuing chaos, Rainwood defends himself, non-fatally wounding an officer. But Parnell and Scalise, realizing their catastrophic error, conspire to frame him, planting drugs and fabricating evidence. Suddenly, the competent, easy-going Jimmie Rainwood is trapped in a nightmare, railroaded by a system meant to protect him. It’s a scenario that taps into primal fears of injustice, the helplessness of being caught in bureaucratic or corrupt gears. Interestingly, the script comes partly from Jim Cash and Jack Epps Jr., the duo better known for the high-flying bombast of Top Gun and the buddy-cop charm of Turner & Hooch. Their involvement here adds a curious layer, grounding their knack for accessible storytelling in something far grittier and more desperate.

Selleck Steps Out of the Ferrari

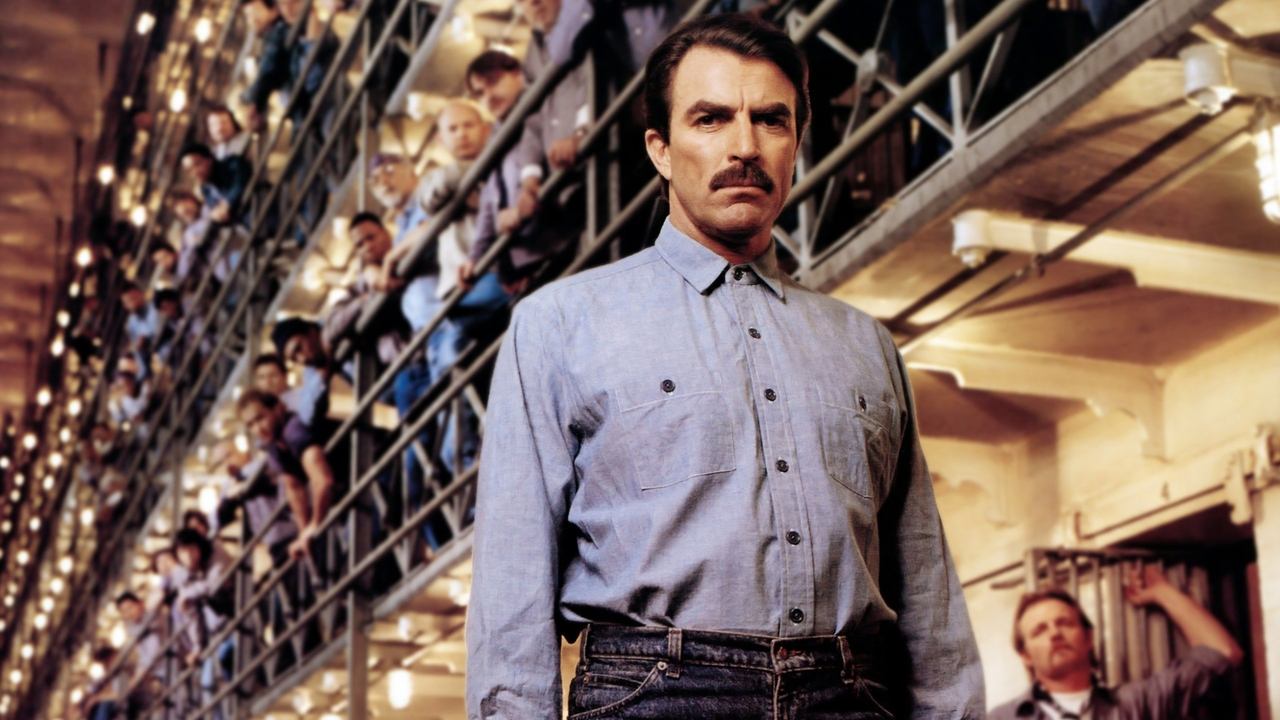

This was a significant role for Tom Selleck. Fresh off eight seasons as the effortlessly cool Thomas Magnum on Magnum, P.I., Selleck clearly sought to stretch his dramatic muscles, shedding the aloha shirts for prison blues. And honestly, he pulls it off admirably. You feel Rainwood's disbelief morphing into terror, then hardening into grim determination. Selleck effectively portrays the physical and psychological toll of incarceration; the way his eyes lose their light, the subtle shifts in posture as he learns the brutal calculus of survival. There's a scene where he first enters the general population, utterly overwhelmed and vulnerable – it’s a powerful piece of acting that relies on presence and reaction rather than dialogue. Selleck reportedly threw himself into the role, keen to prove his range beyond the charismatic private eye, and that commitment shows on screen. He makes Rainwood's transformation from victim to hardened survivor believable.

Lessons in Survival

The film's mid-section plunges us into the bleak reality of prison life. Director Peter Yates, a veteran craftsman known for action classics like Bullitt and acclaimed dramas like Breaking Away, doesn't shy away from the inherent violence and tension. He captures the claustrophobia and the constant threat simmering beneath the surface. It’s here Jimmie meets Virgil Cane, portrayed with quiet, weary authority by the great F. Murray Abraham. Fresh off his Oscar win for Amadeus, Abraham lends immediate gravitas. Virgil isn’t a caricature; he’s a lifer who understands the unwritten rules, the necessity of alliances, and the brutal cost of weakness. His mentorship of Jimmie feels earned, born of grim necessity rather than sentimentality. Their dynamic forms the film's moral and emotional core during this bleak chapter. Watching Abraham work is always a pleasure; he brings such intelligence and weary depth to even small gestures.

Behind the Bars and Budget

Filmed partly on location, including scenes reportedly shot within the imposing walls of the now-closed Nevada State Prison, the film captures an authentic sense of place. Yates uses the environment effectively, contrasting the wide-open skies of Rainwood’s former life with the oppressive concrete and steel of his new reality. It’s worth remembering this film was made for around $19 million and had a fairly modest theatrical run, grossing about $20 million domestically (that's roughly $48M budget yielding $50M box office today – respectable, but not a blockbuster). Yet, like so many solid, well-crafted thrillers of the era, An Innocent Man found a robust second life on VHS and cable. Popping that tape in the VCR felt like settling in for a serious, gripping story – a reliable rental night staple. It wasn't flashy, but it delivered a compelling narrative driven by strong performances.

The Weight of Injustice

While the plot mechanics follow a familiar path – wrongful conviction, prison survival, eventual quest for vengeance – the film resonates because of its focus on the human cost. What does it take to strip away someone's identity? How does institutional brutality reshape a person? Jimmie's journey forces uncomfortable questions about the nature of justice and the corrupting influence of unchecked power. Does the fight for survival inevitably require sacrificing parts of oneself? The film suggests the scars, both physical and psychological, are permanent, even if freedom is regained. The transition back to the outside world and the inevitable confrontation with Parnell and Scalise shifts the tone again, becoming a tense revenge thriller. Yates handles this competently, building suspense towards a satisfying, if somewhat predictable, climax.

Final Verdict

An Innocent Man isn't groundbreaking cinema, perhaps, but it's a remarkably solid and affecting thriller from the late 80s. It rises above its familiar plot thanks to Peter Yates' assured direction and, crucially, the committed performances from its leads. Tom Selleck proves he's more than just a charming mustache, delivering a nuanced portrayal of a man pushed to the edge, while F. Murray Abraham anchors the prison sequences with profound gravitas. The depiction of systemic corruption and the harsh realities of prison life lends it a weight that lingers. It effectively balances tense action with genuine human drama.

Rating: 7/10

Justification: The film earns its score through strong central performances, particularly Selleck's convincing dramatic turn and Abraham's weighty presence. Peter Yates' experienced direction ensures a well-paced, atmospheric thriller. While the plot treads familiar ground within the wrongful conviction/revenge genre, its execution is effective and emotionally engaging. The slightly formulaic structure prevents a higher score, but it remains a compelling and well-crafted piece of late-80s filmmaking that holds up well, especially for fans of the cast or the genre.

It’s one of those VHS tapes that likely saw plenty of wear – a satisfying, thoughtful thriller that reminds us how fragile the line between normalcy and nightmare can truly be.