Okay, pull up a chair, maybe pour yourself something comforting. We’re venturing into territory that isn’t bathed in the neon glow of feel-good 80s nostalgia tonight. Instead, we’re delving into the concrete shadows of a Parisian banlieue with Jean-Claude Brisseau’s devastating 1988 film, Sound and Fury (De bruit et de fureur). This isn't a tape you'd grab for a light Friday night viewing; finding it tucked away in the ‘World Cinema’ section of a well-stocked video store felt like unearthing something potent, something that promised – or perhaps threatened – to leave a mark. And leave a mark it certainly does.

### Echoes in the Concrete Jungle

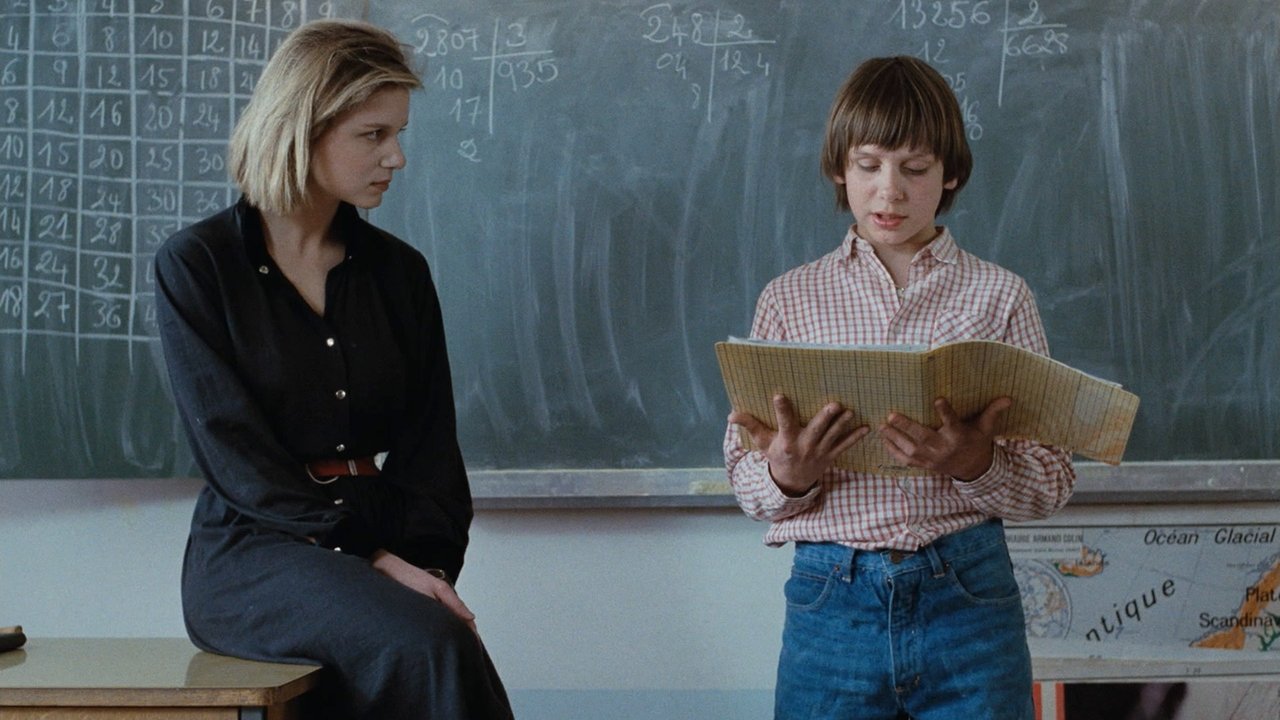

The film plunges us into the life of young Bruno (Vincent Gasperitsch), a quiet, almost unnervingly observant boy who moves with his mother into a soulless housing project in Bagnolet, a suburb east of Paris. It’s a world away from the romanticized image of the city. Here, the concrete towers seem to press inwards, reflecting the suffocating atmosphere of lives lived on the margins. Bruno soon falls under the volatile orbit of Jean-Roger (François Négret), an older teen brimming with a dangerous charisma, whose swagger barely conceals the wounds inflicted by his monstrous father, Marcel (Bruno Cremer).

What unfolds is less a conventional plot and more a descent into a very specific kind of hell. Brisseau, who drew heavily on his own experiences teaching in similarly deprived areas, crafts a portrait of social decay, educational failure, and cyclical violence that feels utterly authentic and deeply unsettling. There’s a rawness here, an unflinching gaze that refuses to look away from the ugliness, the casual brutality, and the crushing despair that permeates this environment. It makes you wonder, doesn't it, about the unseen struggles simmering just beneath the surface of seemingly ordinary places?

### A Father's Shadow, A Son's Rage

At the dark heart of the film lies the relationship between Jean-Roger and Marcel. Bruno Cremer, an actor of formidable presence perhaps best known to international audiences for his intense role in William Friedkin's Sorcerer (1977) or later as the definitive TV Maigret, delivers a performance here that is nothing short of terrifying. Marcel is a figure of pure, nihilistic rage – an alcoholic bully whose abuse shapes his son’s desperate attempts at rebellion and dominance. Cremer embodies him with a chilling weight, making Marcel not just a villain, but a gaping wound of failed masculinity and destructive bitterness.

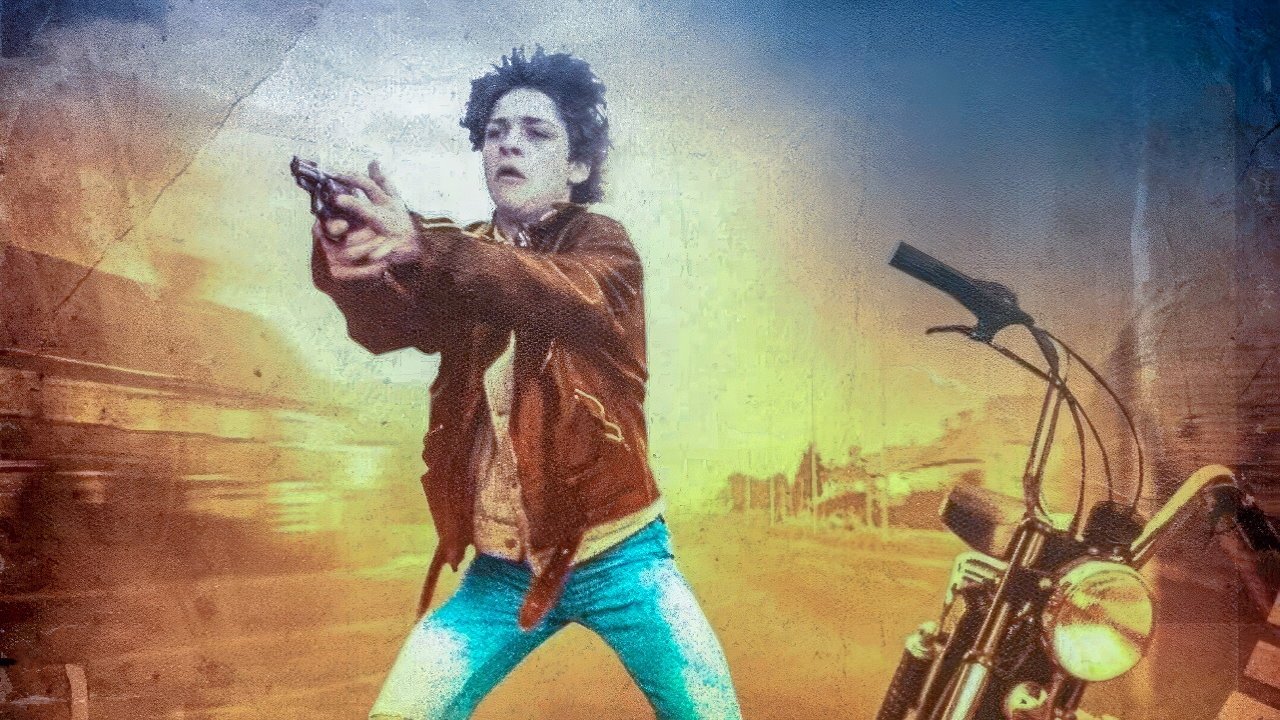

Against this, François Négret matches him with a raw, kinetic energy as Jean-Roger. He’s magnetic and repellent, a victim lashing out, trying to carve out an identity through violence and defiance in a world that offers him little else. His bravado is paper-thin, his vulnerability painfully exposed in fleeting moments. And caught between them is Vincent Gasperitsch’s Bruno, our wide-eyed filter, absorbing the chaos. His quiet passivity is its own kind of commentary, representing perhaps the crushing effect such an environment has on innocence.

### Brisseau's Bleak Poetry

Jean-Claude Brisseau wasn't interested in easy answers or comforting narratives. His direction here is stark, almost documentary-like in its observation of the grim realities, yet punctuated by moments that verge on the surreal – Bruno’s almost sci-fi interactions with an advanced computer, sequences that feel dreamlike, or the sudden, shocking bursts of violence. It’s a style that reflects the fractured reality of the characters' lives. The film’s title, famously borrowed from Shakespeare’s Macbeth – "a tale / Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, / Signifying nothing" – hangs heavy over the proceedings. Is there any meaning to be found in this chaos, or is it all just noise and rage leading nowhere?

It’s fascinating to consider that Sound and Fury garnered significant acclaim, even winning the Special Youth Jury Prize at the 1988 Cannes Film Festival. Brisseau would follow this just a year later with the similarly potent Noce Blanche (1989), launching the cinematic career of Vanessa Paradis. His willingness to confront uncomfortable truths, blending social realism with near-mystical undertones, marked him as a distinctive voice in French cinema. Filming on location in the actual Cité Karl Marx housing project in Bobigny (standing in for Bagnolet) adds another layer of authenticity, making the environment itself a character – oppressive and inescapable.

### Not Your Average Rental, But A Necessary One?

Let's be honest, Sound and Fury probably wasn't flying off the rental shelves next to Die Hard or Beetlejuice. It’s a demanding watch, bleak and often brutal. Yet, stumbling upon films like this during the VHS era was part of the magic, wasn't it? It was about more than just entertainment; it was about discovery, about encountering voices and visions from far outside our usual comfort zones. This film doesn't offer the warm fuzzies of nostalgia, but it represents a vital aspect of that period – the potential for cinema, even on a flickering CRT screen via a worn-out tape, to challenge us, provoke us, and force us to confront difficult realities. It reminds us that even amidst the blockbusters and genre flicks, powerful, uncompromising art was finding its way into our homes.

The film leaves you wrestling with difficult questions. What responsibility does society bear for creating such environments? Can the cycle of violence ever truly be broken? Brisseau offers no simple solutions, just the stark depiction of lives consumed by desperation.

Rating: 8/10

This rating reflects the film's undeniable power, its artistic integrity, and the haunting performances, particularly from Cremer and Négret. It's a technically accomplished and thematically resonant piece of uncompromising filmmaking. The deduction comes not from a lack of quality, but from its sheer bleakness and intensity, which makes it a profoundly difficult and potentially alienating viewing experience for some. It earns its impact through sheer force, but it’s not a journey everyone will want to take.

Sound and Fury is a potent reminder from the shelves of VHS Heaven that sometimes, the most vital films are the ones that leave you feeling shattered, questioning everything long after the tape has ejected. It's a howl from the margins, echoing with uncomfortable truths.