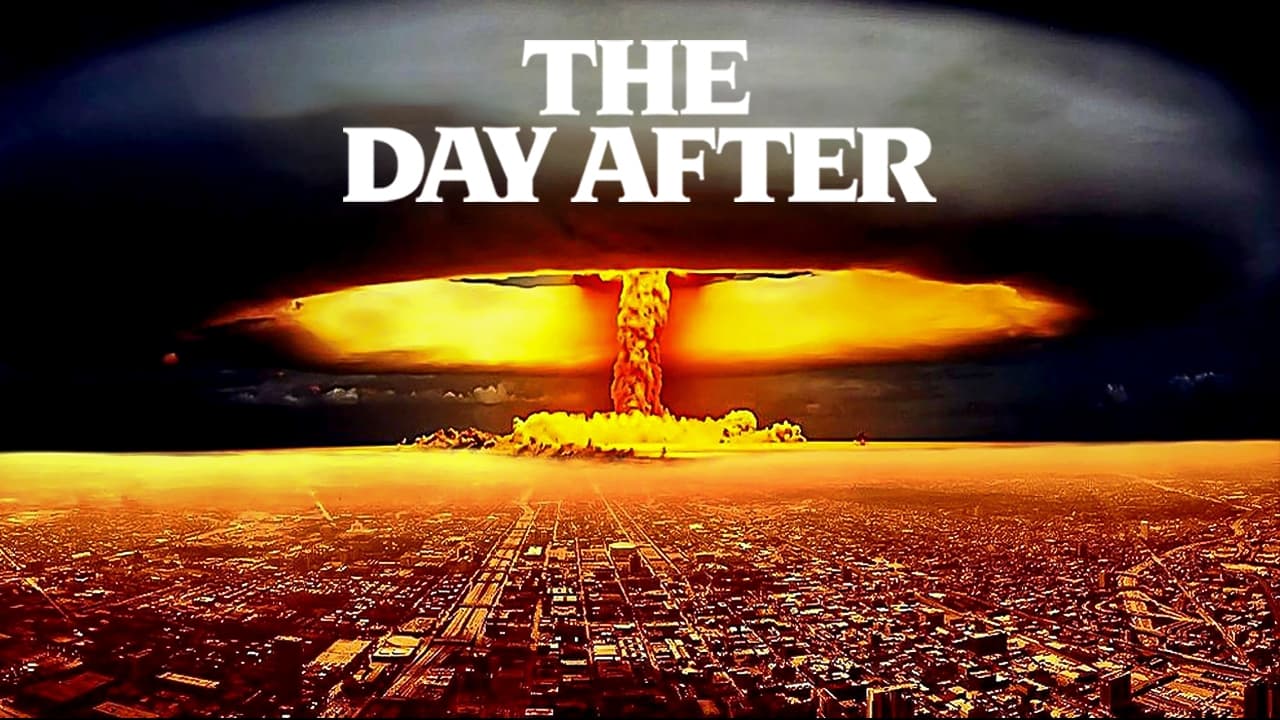

Alright, let's dim the lights, maybe pour something contemplative, and talk about a television event that felt less like entertainment and more like a national wake-up call. I’m talking about The Day After, the 1983 ABC TV movie that landed in living rooms across America with the force of a shockwave, leaving a silence that felt heavier than any explosion depicted on screen. For many of us glued to our CRT sets that November night, it wasn’t just another movie rental feeling; it was a shared, sobering experience that brought the abstract horror of nuclear war into sharp, terrifying focus.

### The Unspeakable Knock at the Door

What haunts me most, revisiting The Day After now, isn't necessarily the mushroom clouds – though they remain chilling – but the sheer, crushing ordinariness of life just before the unthinkable happens. Director Nicholas Meyer, perhaps unexpectedly chosen given his success with the relatively optimistic Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982) just the year before, anchors the film firmly in the mundane reality of Lawrence, Kansas, and surrounding communities. We meet Dr. Russell Oakes (Jason Robards), caught between his hospital duties and family life; Jim Dahlberg (John Cullum) and his family preparing for a wedding; young university students like Stephen Klein (Steve Guttenberg, in a role far removed from his Police Academy antics) simply living their lives. The film patiently builds this tapestry of everyday concerns – homework, farming, relationships – making the sudden, almost procedural depiction of escalating global tensions utterly terrifying. There's no Hollywood gloss, just news reports crackling in the background, a growing sense of dread that tightens like a knot in your stomach.

### When the Sky Fell

The attack sequence itself is executed with a brutal lack of sensationalism. Meyer, working within the constraints of a television budget (around $7 million, a hefty sum for TV then but requiring ingenious solutions) and network standards, relies less on graphic spectacle and more on suggestion and the chillingly impersonal perspective of missile launches and distant detonations. Stock footage was carefully interwoven with newly created effects, aiming for a terrifying plausibility rather than pyrotechnic excess. The film deliberately avoids showing us the 'ground zero' gore that might have felt exploitative. Instead, the horror unfolds through the characters' dazed incomprehension, the sudden loss of power, the eerie silence punctuated by the rising wind. I distinctly remember the feeling watching this as a teenager – not excitement, but a cold, creeping fear. It felt possible.

One fascinating production tidbit: Meyer was reportedly brought onto the project after the original director was let go, and he insisted on a less overtly political, more human-focused approach. He aimed for realism, consulting scientists like Carl Sagan and even requesting (and being denied) footage of actual nuclear tests to study the effects. The goal wasn't jingoism or anti-Soviet propaganda, but a stark portrayal of the consequences, regardless of who pushed the button first.

### The Grim Reality of Survival

Where The Day After truly digs its claws in is the extended depiction of the aftermath. This isn't a story of heroic survival against the odds; it's a slow, agonizing descent into chaos, sickness, and despair. The film unflinchingly portrays the breakdown of society: overwhelmed hospitals, dwindling resources, the invisible killer of radiation poisoning. Jason Robards, a true heavyweight actor, grounds the film with his portrayal of Dr. Oakes. His exhaustion, his dawning realization of the futility of his efforts, is palpable. You see the weight of the world settle onto his shoulders, the experienced physician reduced to near helplessness. His performance isn't showy; it's devastatingly quiet, conveying a deep, soul-crushing weariness that feels utterly authentic.

Similarly, JoBeth Williams as nurse Nancy Bauer embodies the desperate struggle to maintain humanity amidst the collapse. Her journey, particularly her concern for her children, provides a vital emotional anchor. And Steve Guttenberg, as the student trying to navigate the ravaged landscape to find his family, represents the bewildered younger generation grappling with a future utterly obliterated. These aren't action heroes; they are ordinary people stripped bare, their courage measured in small acts of compassion or simply the will to endure another hour. The makeup effects depicting radiation sickness, while perhaps tame by today's standards, were shocking for network television in 1983 and contributed significantly to the film's grim power.

### Echoes in the Fallout Shelter

The impact of The Day After was unprecedented. Over 100 million people tuned in – nearly half the country – making it the highest-rated TV movie in history at the time. ABC even set up 1-800 hotlines and aired a special discussion panel hosted by Ted Koppel immediately afterward, featuring figures like Henry Kissinger and Carl Sagan, acknowledging the profound national conversation the film had ignited. It wasn't universally praised; critics were divided, and the Reagan administration, while publicly stating the film justified their arms buildup, was reportedly concerned about its potential effect on public opinion regarding nuclear policy.

But its cultural resonance was undeniable. Did it change policy overnight? Perhaps not directly. But did it force millions to confront a reality they preferred to ignore? Absolutely. It bypassed political rhetoric and spoke directly to primal fear and the human cost of conflict. It made the abstract concept of Mutually Assured Destruction feel terrifyingly personal. For those of us who remember renting the slightly worn VHS tape, maybe sharing it nervously with friends, The Day After remains more than just a movie. It was a shared cultural moment, a stark warning etched onto magnetic tape.

Rating: 9/10

This near-perfect score isn't for flawless filmmaking in the traditional sense – it is a TV movie with certain inherent limitations. But its rating reflects its staggering cultural impact, its courageous (for the time) depiction of an unthinkable subject, the strength of its core performances, and its chilling effectiveness in achieving its terrifying goal. Meyer crafted not just a film, but a crucial piece of Cold War commentary that resonated deeply.

The Day After doesn't offer easy answers or comforting resolutions. It leaves you with the silence, the dust, and the profound, unsettling question: what happens next? That question, perhaps, is its most enduring legacy.