Imagine browsing the video store shelves in 1988, perhaps hunting for the latest Stallone epic or a neon-soaked slasher flick. Past the familiar box art, you might have stumbled upon something utterly alien: a Polish film, stark and unsettling, bearing the simple, ominous title The Devil (Diabeł). Its arrival on VHS wasn't a typical new release; it was the delayed unearthing of a volatile cinematic artifact, filmed sixteen years earlier in 1972 and promptly banned by Poland's communist authorities. Finding Andrzej Żuławski's The Devil back then must have felt less like renting a movie and more like discovering a forbidden text, whispering of historical trauma and political defiance.

A Mud-Caked Descent

Forget conventional horror tropes. The Devil plunges us headfirst into the brutal chaos of the 1793 Prussian invasion of Poland. We meet Jakub (Leszek Teleszyński), a young nobleman languishing in a convent-turned-prison, seemingly spared execution at the last moment by a mysterious, black-clad stranger (Wojciech Pszoniak). This stranger offers Jakub freedom, a horse, a bag of gold, and a straight razor, dispatching him back to his family estate. What follows is not a tale of heroic resistance, but a harrowing, almost hallucinatory journey through a landscape ravaged by war, moral decay, and encroaching madness. Żuławski, already known for his intense vision after 1971's Third Part of the Night, crafts an atmosphere thick with mud, blood, and palpable despair. It’s a far cry from the creature features or supernatural hauntings common in the era’s video rentals; this horror feels historical, psychological, deeply rooted in human cruelty and societal collapse.

The Puppet Master and the Unraveling Soul

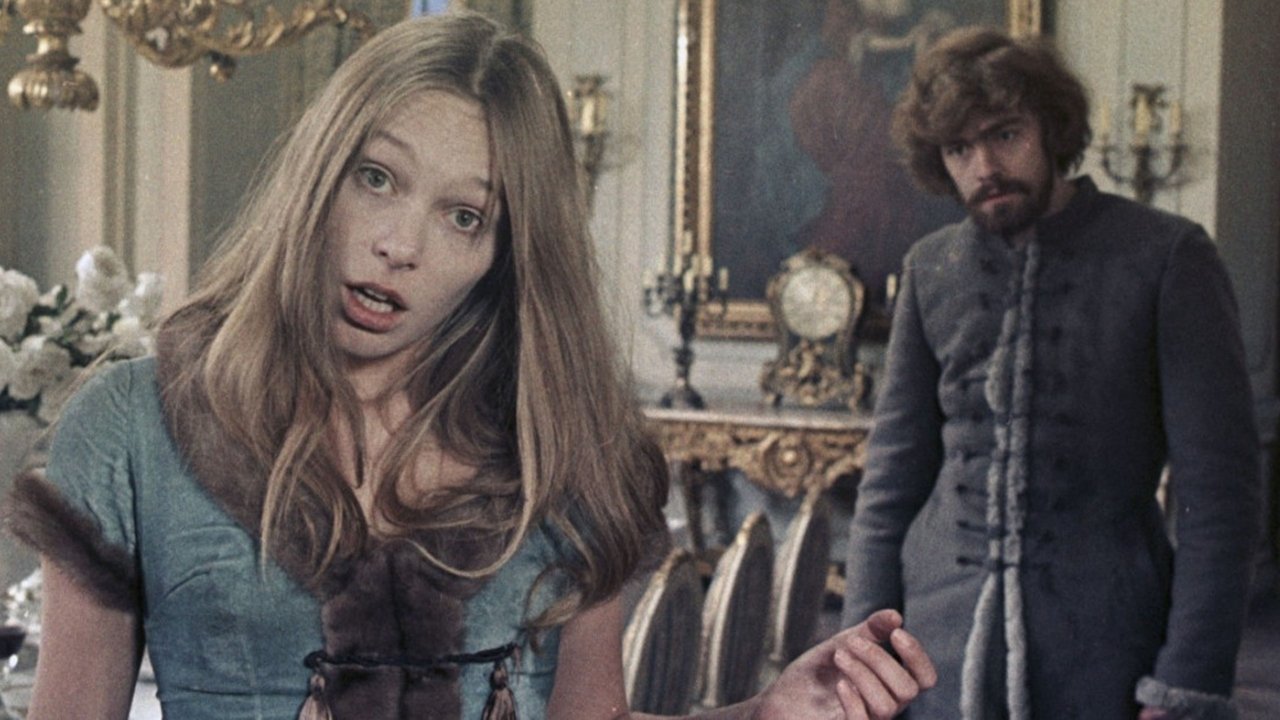

Leszek Teleszyński carries the immense weight of the film as Jakub. His transformation from a bewildered prisoner to an instrument of vengeance and, ultimately, a man consumed by the darkness he witnesses and perpetrates, is staggering. His wide eyes initially reflect shock, then a dawning horror, and finally, a terrifying emptiness. It’s a physically and emotionally demanding performance, capturing the disintegration of a soul amidst utter bedlam.

But it's Wojciech Pszoniak as the stranger who truly chills. Is he merely a cynical manipulator, an agent provocateur exploiting the chaos for unknown ends? Or is he something more... infernal? Pszoniak plays him with a captivating blend of unnerving calm, sardonic amusement, and underlying menace. He doesn't need horns or overt supernatural displays; his power lies in his whispers, his suggestions, his uncanny ability to appear exactly when Jakub is most vulnerable, pushing him further down the path of destruction. Their dynamic forms the twisted heart of the film – the puppet master and the unraveling soul. Adding another layer of tragic intensity is Małgorzata Braunek (who also starred in Third Part of the Night and would later work with Żuławski again), whose character becomes entangled in Jakub's increasingly desperate and violent trajectory.

A Film Too Dangerous: The Story Behind the Ban

Understanding The Devil requires grasping its tumultuous creation. Filmed in 1972, it was immediately banned by the Polish government and wouldn't see the light of day until 1988. Why? While set in the 18th century, authorities saw its depiction of societal breakdown, treacherous informants, cynical manipulation, and pervasive madness as a thinly veiled allegory for the 1968 Polish political crisis and the subsequent government crackdown on dissent. The film's relentless bleakness, its questioning of authority (both human and potentially divine), and its sheer frenetic, challenging style were deemed too subversive, too dangerous for public consumption. Żuławski poured his frustrations and anger into the project, creating a work of raw, confrontational energy. Its sixteen-year suppression only added to its mystique, turning it into a legendary piece of censored cinema finally unleashed on an unsuspecting late-80s audience, likely more accustomed to the escapism of Top Gun (1986) than the existential dread of Polish historical horror.

Żuławski's Operatic Nightmare

If you've seen Żuławski's other demanding masterwork, Possession (1981), you'll recognize the stylistic DNA here. The camera rarely rests, often swirling, lurching, and pushing in uncomfortably close on faces contorted in anguish or ecstasy. The editing is sharp, sometimes jarring, mirroring the characters' fractured states of mind. Performances across the board are pitched at a level of heightened, almost operatic intensity – a deliberate choice that amplifies the film's nightmarish quality. This isn't realism; it's expressionism dialed up to eleven, a cinematic scream against historical trauma and political oppression. It’s a demanding watch, requiring patience and a strong stomach, but the artistic conviction is undeniable.

What Lingers in the Dark?

The Devil doesn't offer easy answers. It leaves you grappling with profound questions. What truly constitutes evil – a supernatural force, or the depths of human depravity unleashed by chaos? How easily can idealism be twisted into violence when guided by cynical hands? Doesn't the film's portrayal of manipulation and societal breakdown under duress still resonate, echoing challenges far beyond its specific historical or political context? It’s a film that burrows under your skin, its disturbing imagery and bleak philosophy lingering long after the credits roll. It forces a confrontation with the darker aspects of history and human nature.

Rating: 8/10

This rating reflects the film's undeniable artistic ambition, its historical significance as a piece of banned cinema, and the sheer, unforgettable power of its central performances and nightmarish atmosphere. Andrzej Żuławski crafted something utterly unique and uncompromising. However, the 8 acknowledges its demanding, often abrasive nature; its relentless intensity and challenging style make it a difficult, even alienating experience for some viewers. It's not a film you casually "enjoy," but one you wrestle with, admire for its audacity, and ultimately, can't easily forget.

Finding The Devil on a dusty VHS tape must have been a jolt – a raw, unfiltered dispatch from a different kind of darkness. It remains a potent, challenging piece of filmmaking, a testament to artistic defiance that finally clawed its way out of censorship's shadow.