The air hangs thick and shimmering, distorted by waves of heat rising from the asphalt gridlock. Horns blare a dissonant symphony of frustration, a sound baked into the very soul of early 90s Los Angeles. It’s here, amidst the exhaust fumes and the boiling tempers, that something inside William "D-Fens" Foster finally cracks. Falling Down doesn't ease you into its dread; it plunges you headfirst into the pressure cooker, forcing you to witness the precise moment a man’s carefully constructed reality buckles under the weight of a world he no longer recognizes, or perhaps, never truly did.

The Breaking Point

The setup is deceptively simple: a recently laid-off defense worker, separated from his wife and child, abandons his car in standstill traffic and decides to walk home. Across town. On foot. Through the urban sprawl of LA. What follows is less a journey and more of a descent, a series of increasingly volatile encounters fueled by perceived slights, bureaucratic absurdity, and a simmering rage that’s been searching for an outlet. Joel Schumacher, a director often associated with stylish spectacle like The Lost Boys (1987) or Flatliners (1990), here strips away the gloss, delivering a gritty, sun-bleached nightmare that feels alarmingly grounded. The tension doesn't come from jump scares, but from the chillingly relatable frustrations D-Fens weaponizes, pushing the mundane irritations of modern life towards violent extremes. You watch, holding your breath, knowing each step takes him further from any possibility of turning back.

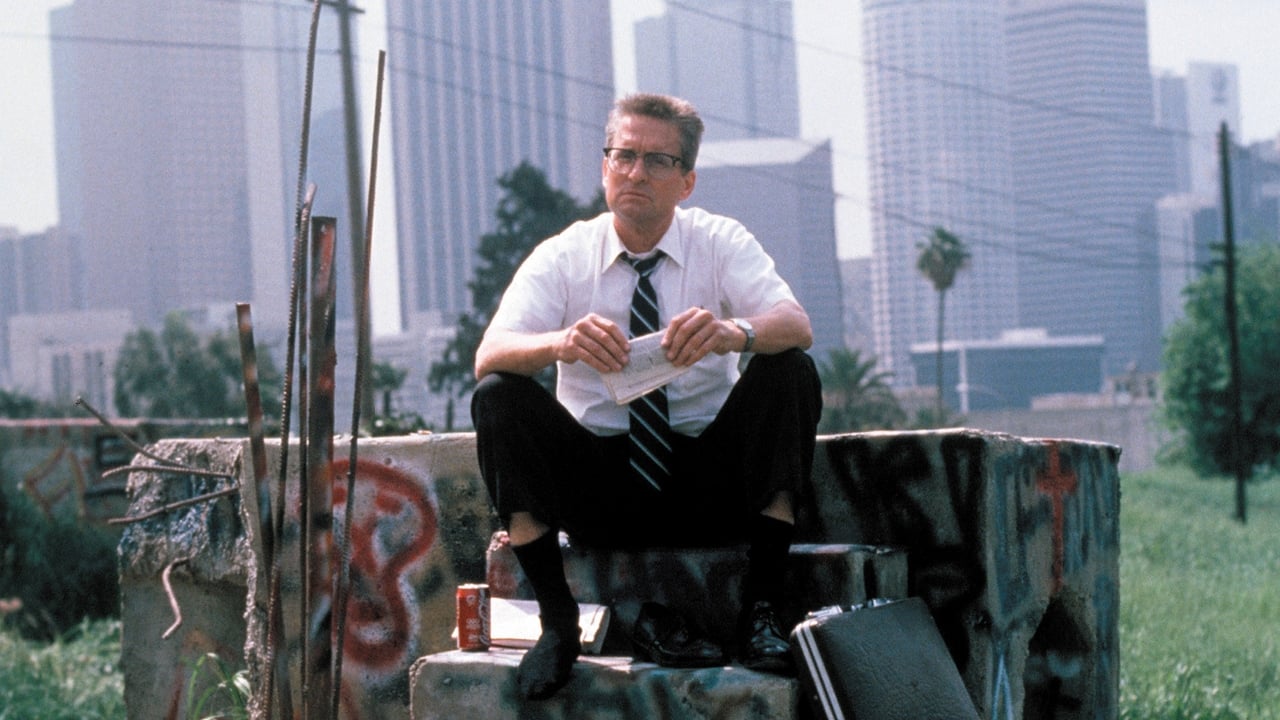

The Man in the White Shirt

At the heart of this simmering cauldron is Michael Douglas, delivering a performance that’s become iconic, and for good reason. His D-Fens, with the severe flat-top haircut, the crisp white shirt clinging with sweat, the thick-rimmed glasses, and the ever-present briefcase, is a terrifyingly ordinary monster. Douglas, who reportedly chased the role aggressively after reading Ebbe Roe Smith’s lauded (and previously unproduced "Black List") screenplay, embodies a man whose entire identity has been stripped away, leaving only resentment. Is he an anti-hero speaking truth to power, or a dangerously unstable bigot lashing out? The film masterfully walks this tightrope, forcing uncomfortable introspection. Douglas avoids easy caricature; there’s a chilling blankness behind the eyes, a meticulousness to his meltdown that makes him all the more unsettling. Remember watching him calmly retrieve the baseball bat? That quiet intensity felt profoundly disturbing on a fuzzy rental tape, the lack of histrionics somehow amplifying the threat.

A Sun-Drenched Inferno

Los Angeles itself becomes a crucial character, presented not as the land of dreams but as a sprawling, fractured landscape simmering with latent hostility. Schumacher and cinematographer Andrzej Bartkowiak capture the relentless glare of the California sun, making the heat palpable, oppressive. The locations aren't glamorous landmarks but the anonymous freeways, rundown convenience stores, sterile fast-food chains, and forgotten patches of wasteland that define the city’s vast, indifferent sprawl. Filming that legendary opening traffic jam sequence on the Pasadena Freeway reportedly caused genuine gridlock, a meta-moment reflecting the very frustrations the film dissects. This isn't Hollywood; it's the pressure cooker where everyday anxieties boil over.

The Weary Watchman

Providing the crucial counterpoint is Robert Duvall as LAPD Sergeant Martin Prendergast. On his last day before retirement, dealing with his own anxieties and the gentle nagging of his wife, Prendergast is the weary, methodical conscience of the film. As D-Fens carves a path of destruction driven by impulse and rage, Prendergast meticulously pieces together the puzzle, representing a different kind of resilience – the quiet endurance needed to navigate a flawed world without completely losing oneself. Duvall brings his trademark authenticity, grounding the film's more heightened moments. His quiet observations and world-weary sighs offer a necessary anchor against D-Fens's explosive trajectory.

Moments Under the Microscope

The film unfolds as a series of vignettes, each encounter escalating the stakes and revealing another facet of D-Fens's unraveling psyche and the societal friction points he collides with. The infamous Whammy Burger scene ("I want breakfast!"), apparently a later addition to the script, became an instant classic, perfectly encapsulating the absurdity of inflexible rules meeting boiling frustration. Then there's the tense standoff in the Korean grocery store, a scene that drew protests from Korean-American groups upon release, highlighting the film's controversial engagement with racial tensions. Or the darkly comic, yet deeply menacing, encounter with the Neo-Nazi surplus store owner, played with chilling conviction by Frederic Forrest (Apocalypse Now). Each set piece feels like another turn of the screw, pushing D-Fens – and the audience – further into uncomfortable territory. It tapped into something raw in 1993, a feeling that the system wasn't just broken, but actively hostile.

Legacy of Unease

Falling Down hit a nerve upon release, becoming a surprise box office success (grossing over $96 million worldwide on a $25 million budget) and sparking fierce debate. Was it a dangerous validation of white male rage? A sharp critique of societal decay? A cautionary tale? Or all of the above? Watching it today, some elements inevitably feel dated, locked into the specific anxieties of the early 90s. Yet, its core themes of alienation, economic anxiety, and the feeling of being utterly powerless against vast, impersonal forces remain disturbingly relevant. Doesn't that final confrontation on the pier still carry a heavy weight? The sense of inevitability, of a journey that could only end one way?

VHS Heaven Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's sheer power and Michael Douglas's unforgettable, complex performance. The atmosphere is thick with palpable tension, Joel Schumacher directs with a surprising grit, and the script offers a provocative, if controversial, snapshot of societal breakdown. It masterfully builds dread without resorting to cheap tricks, forcing viewers into an uncomfortable space alongside its protagonist. While some aspects invite debate regarding its social commentary, its effectiveness as a gripping, unsettling thriller is undeniable. Falling Down is more than just an "angry white man" movie; it's a pressure-cooker study of societal friction and individual collapse that lingers long after the tape clicks off, a stark reminder of how close any of us might be to simply… walking away.