Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland

Step into a dream, won't you? Not just any dream, but one painted with the lavish, sometimes unsettling, beauty of Winsor McCay's imagination, filtered through the lens of late-80s animation ambition. Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland (1989) arrived on video store shelves like a whispered promise of pure fantasy, a portal to a world operating entirely on the logic of sleep. For many of us clutching that worn VHS box, it felt like unearthing a secret – a visually stunning adventure that perhaps didn't roar like Disney's lions but certainly captivated with its unique, sometimes surreal, charm. It wasn't just another cartoon; it felt like stepping into someone else’s vibrant, slightly chaotic dreamscape.

### A Bed That Flies and a Promise Made

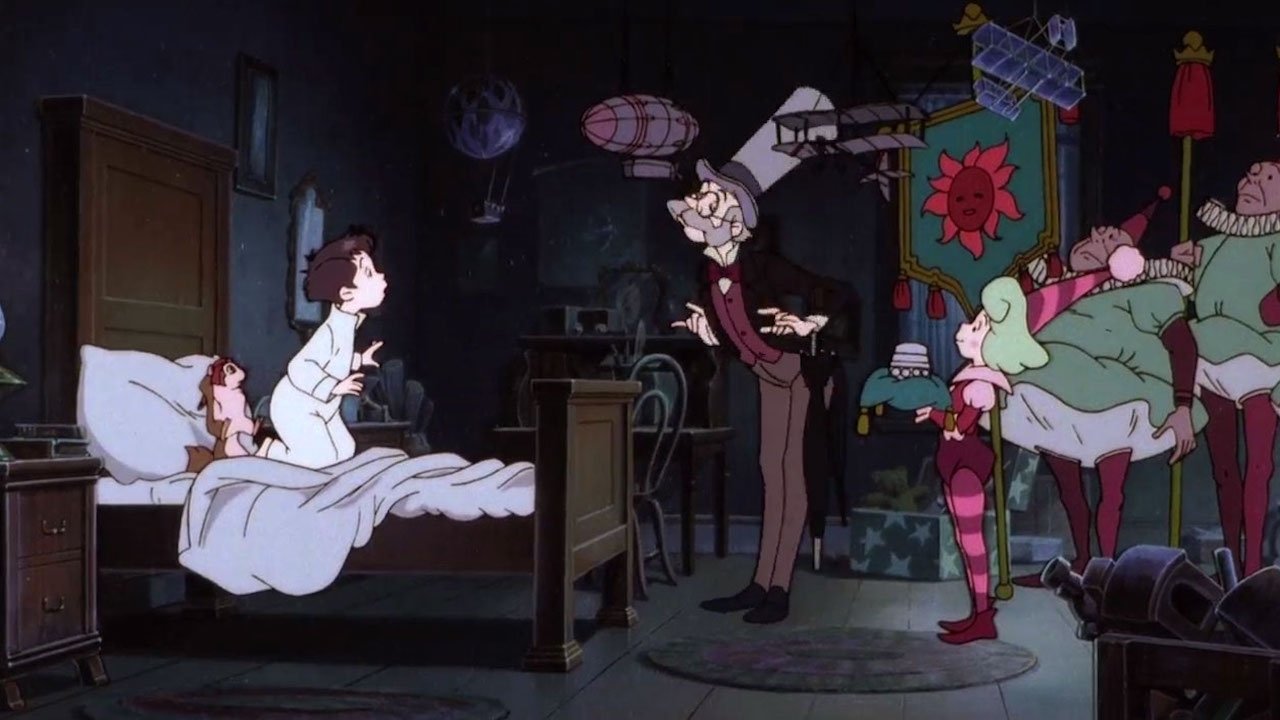

The setup is pure childhood wish-fulfillment mixed with classic fairy tale structure. Young Nemo (Gabriel Damon, lending an earnest voice to our pajama-clad hero) is whisked away one night, not by sleigh bells or fairy dust, but by his own bed, soaring through the cityscape towards the luminous gates of Slumberland. He’s summoned by the kindly Professor Genius (Rene Auberjonois, delightfully eccentric) to be the playmate of Princess Camille. King Morpheus (Mickey Rooney, bringing his signature energetic charm) sees Nemo as a potential heir, bestowing upon him a golden key capable of unlocking any door in the kingdom, with one solemn warning: never open the door bearing a specific dragon insignia. And if you remember anything about childhood curiosity and storytelling, you know exactly where that’s headed.

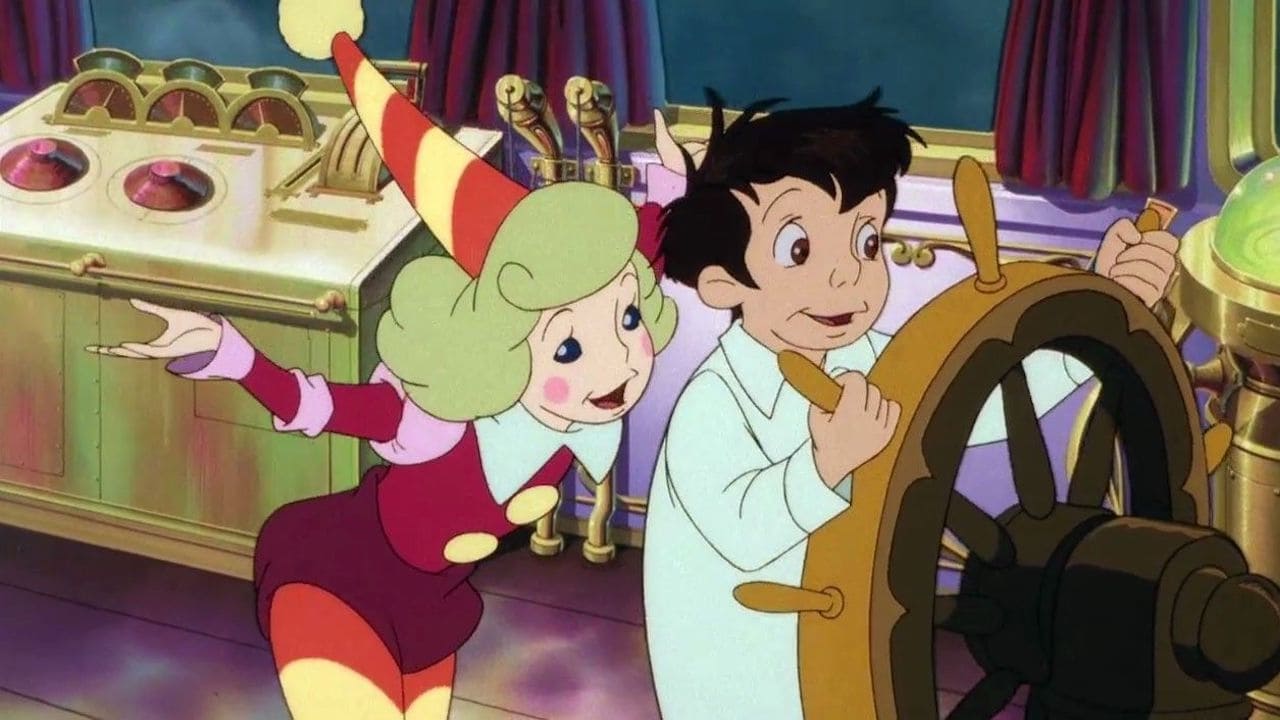

What follows is less a tightly plotted narrative and more a series of wondrous, beautifully animated vignettes. Nemo befriends the mischievous, cigar-chomping Flip (Mickey Rooney again, pulling double duty with gusto), explores dazzling palaces, rides a majestic train across the clouds, and generally lives out the kind of fantastical adventures that felt ripped straight from the most vivid recesses of a child's imagination. This episodic feel mirrors the source material – McCay's groundbreaking early 20th-century comic strip – which often prioritized breathtaking visuals and dreamlike scenarios over linear storytelling.

### Animation Fit for a Dream King

Visually, Little Nemo is often breathtaking. A joint effort between Japanese and American teams, spearheaded by directors Masami Hata and William Hurtz, the animation possesses a richness and fluidity that stands out even today. The character designs are appealing, the backgrounds are lush and detailed, and certain sequences – like the initial flight to Slumberland or the waltz in the royal ballroom – are simply gorgeous. The sheer scale of Slumberland feels vast and imaginative, a world you genuinely want to explore alongside Nemo. It's a testament to the craft of traditional animation, a style that was nearing its zenith before the digital revolution took hold. Watching it now, especially remembering those CRT TV days, the vibrancy still pops, a reminder of the artistry poured into every frame.

### Decades in the Making: A Troubled Slumber

Behind the magic on screen lies one of animation's most famously protracted production stories. The journey to bring McCay's vision to film spanned decades, not years. Seriously, talks began as early as the 1970s! Producer Yutaka Fujioka was obsessed, pouring immense resources into the project. At various points, legends like George Lucas, Chuck Jones, Ray Bradbury, and even future Studio Ghibli titans Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata were involved, only to depart due to creative differences or the project's sheer inertia. The final script bears the names of Chris Columbus (just before he struck gold with Home Alone (1990)) and Richard Outten. This epic, often troubled development history, including a reported budget swelling to around $35 million (a colossal sum for animation then), perhaps explains some of the film's narrative inconsistencies. It feels, at times, like different visions stitched together – beautiful, yes, but not always seamless. It ultimately underperformed at the US box office, recouping only about $11.4 million domestically, making it a financial disappointment despite its artistic merits.

### Shadows in Slumberland

And then there's the Nightmare King. When Nemo inevitably uses that forbidden key (come on, we all knew he would!), he unleashes a genuinely terrifying entity and his shadowy minions upon the idyllic dream world. This shift towards darker territory can be quite jarring. The Nightmare King is pure, oozing malevolence, a stark contrast to the candy-colored wonders seen earlier. For younger viewers back in the day, these sequences could be properly scary – maybe even the reason the tape got hastily ejected! While it adds dramatic stakes, the tonal leap feels abrupt, contributing to the feeling that Little Nemo isn't quite sure exactly what kind of children's film it wants to be. It's ambitious, tackling themes of responsibility and consequence, but the execution sometimes stumbles between whimsical adventure and nightmare fuel. And who could forget the tie-in NES game, Little Nemo: The Dream Master? For many, that notoriously difficult side-scroller is actually more famous than the film it was based on!

### A Flawed Gem from the Dream Factory

Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland remains a fascinating piece of animation history. It's a gorgeous artifact from a time when international co-productions aimed for epic fantasy, even if the storytelling didn't always match the visual splendor. It captures that specific late-80s/early-90s animated film feeling – earnest, ambitious, slightly strange, and utterly unique. Watching it today evokes a powerful sense of nostalgia, not just for the film itself, but for the era of grand animated features that weren't afraid to be a little weird, a little dark, and visually spectacular. It didn't quite become the timeless classic its creators hoped for, overshadowed perhaps by the Disney Renaissance kicking into high gear around the same time, but its imaginative spirit and artistic beauty still resonate.

Rating: 7/10

The score reflects the film's undeniable visual artistry, memorable characters like Flip, and ambitious dream-world creation. The deduction comes from its somewhat disjointed narrative, occasionally jarring tonal shifts, and the fact that its troubled production seems subtly evident on screen. It's a beautiful dream, but one that sometimes loses its way.

For fans of animation history or anyone seeking a trip back to a uniquely imaginative corner of the VHS era, Little Nemo is a journey well worth taking again, perhaps with a comforting blanket and the knowledge that even nightmares eventually end.