"Europa Calling. You want to be in Europa..."

The voice, deep and sonorous, seems to emanate directly from the grainy static of the VHS tape itself, pulling you under before the first frame truly registers. It’s a command, a hypnotic suggestion that perfectly primes you for the disorienting journey ahead. Lars von Trier’s 1991 nightmare, Europa (or Zentropa, as it’s sometimes known), isn’t just watched; it's experienced, a descent into the fractured psyche of post-war Germany that feels less like a movie and more like a fever dream meticulously projected onto celluloid. Forget cosy nostalgia for a moment; this is the kind of tape you rented late one night, perhaps drawn by the stark cover art, only to find yourself pinned to the sofa, unnerved and utterly captivated by its oppressive beauty.

A Train Ride into Shadow

We follow Leopold Kessler (Jean-Marc Barr, familiar to many from Luc Besson's The Big Blue), an idealistic young American of German descent who arrives in Allied-occupied Germany in 1945. Seeking to help rebuild the shattered nation, he takes a job as a sleeping car conductor on the Zentropa railway line. Naivety clings to him like the damp chill of the bombed-out cities he travels through. He wants to remain neutral, an observer, but neutrality is a luxury this poisoned landscape cannot afford. Germany, even in defeat, is a labyrinth of lingering Nazism, Allied bureaucracy, industrialist conspiracy, and the desperate ghosts of war. Leopold is immediately caught in the web, particularly through his association with the Hartmann family, owners of the railway, and the enigmatic, damaged Katharina Hartmann (Barbara Sukowa, a powerful presence often seen in Fassbinder's work).

Von Trier doesn’t just tell this story; he submerges us in its dread. The film’s atmosphere is thick enough to choke on. Shot primarily on soundstages, the production design creates a Germany that feels both hyper-real and nightmarishly artificial. Towering, expressionistic sets dwarf the characters, while the constant rumble and claustrophobia of the train compartments mirror Leopold’s increasing entrapment. The score, punctuated by haunting strings and industrial noise, cranks the tension notch by insidious notch.

Visions in Black, White, and Blood

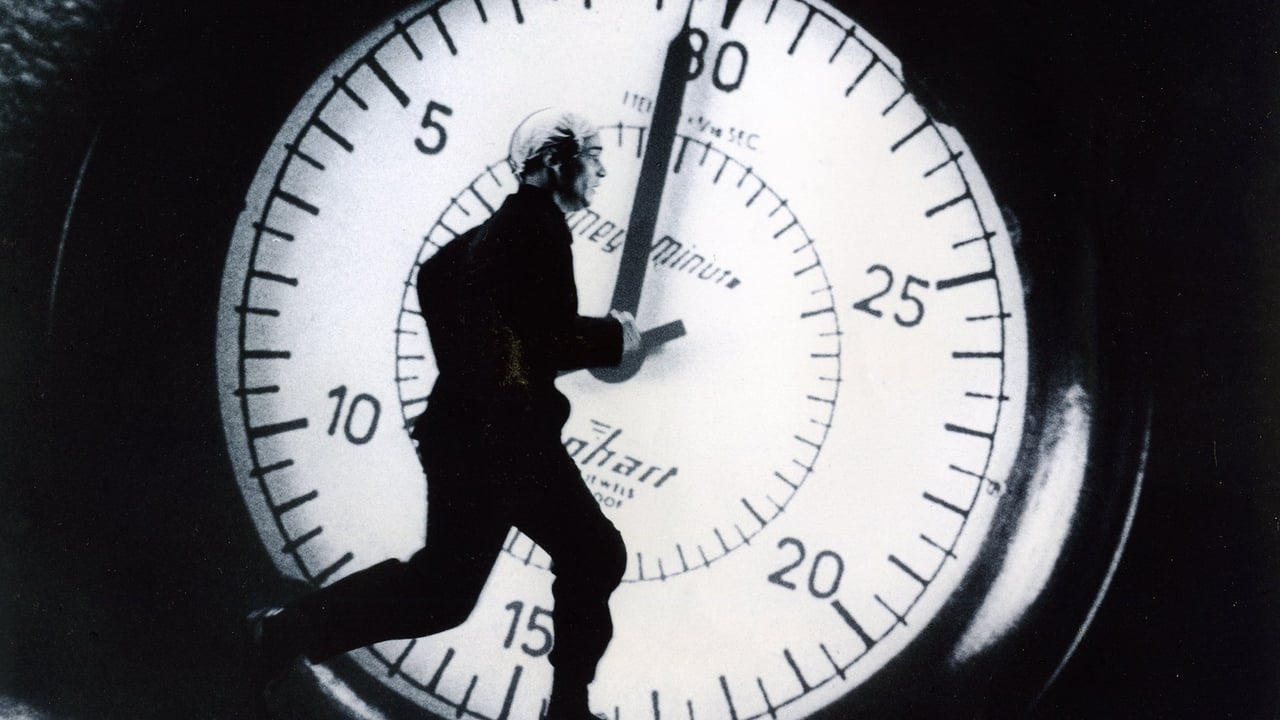

What truly sets Europa apart, and what likely burned itself into your memory if you caught it back in the day, is its revolutionary visual style. Von Trier and cinematographer Henning Bendtsen employ a complex system of back projection and layered imagery, creating scenes where characters seem to glide through static backgrounds, blurring the lines between foreground and background, reality and illusion. It’s deliberately disorienting, forcing you into Leopold’s destabilized perspective.

The masterstroke, however, is the selective use of color. The film unfolds largely in a rich, deep black and white, evoking classic noir and the starkness of the era. But then, suddenly, jarringly, colour erupts – the crimson of blood, the blue of Katharina's eyes, the sickly yellow of a light. This wasn't just a gimmick; it felt profound, like brief, painful intrusions of raw emotion or brutal reality into the monochrome numbness of trauma. Achieving this effect pre-digital required painstaking optical printing work, a technical feat that reportedly pushed the crew to the brink. The result is breathtakingly unique, a visual language that underscores the film’s themes of hidden motives and fractured perception. Doesn't that unexpected splash of red still feel potent, even now?

An Uncompromising Vision

This wasn't a film designed for easy consumption. It demands attention, patience, and a willingness to be unsettled. Jean-Marc Barr perfectly embodies Leopold's slide from wide-eyed hope to compromised despair, his expressive face a canvas for the moral corrosion taking place. Barbara Sukowa is magnetic as the femme fatale wrestling with her own dark past, and the legendary Udo Kier brings his trademark intensity to his role as Lawrence Hartmann, her conflicted brother.

Europa famously won the Jury Prize at the 1991 Cannes Film Festival (alongside several technical awards), but Lars von Trier, ever the provocateur, reportedly expressed disappointment at not winning the Palme d'Or, allegedly flipping off the jury. It’s a tidbit that speaks volumes about the director's uncompromising, often confrontational approach, already evident in this early masterpiece. This was the closing chapter of his "Europa Trilogy" (following The Element of Crime (1984) and Epidemic (1987)), cementing his status as a major, challenging voice in world cinema. While perhaps not a staple at every corner video store, finding Europa felt like unearthing a dark, sophisticated secret – a challenging counterpoint to the era's blockbusters.

The Verdict

Europa is a demanding, hypnotic, and technically astonishing piece of filmmaking. It plunges the viewer into a moral twilight zone, using its groundbreaking visuals and oppressive atmosphere to explore themes of guilt, complicity, and the impossibility of neutrality in the face of historical horror. It’s not a comfortable watch, and its deliberate pacing and stylization might test some viewers. However, its power to disturb and mesmerize remains undiminished. It’s a stark reminder of how ambitious and unsettling cinema could be, even on a fuzzy VHS tape viewed late at night. The dread lingers, just as Max von Sydow's opening narration promised it would.

Rating: 9/10

This near-perfect score reflects the film's stunning technical achievements, its powerful atmosphere, and its lasting impact as a unique and challenging work of art. It's a high point of 90s European cinema, perfectly embodying the dark intensity we sometimes sought out in those late-night video rentals, even if it left us feeling distinctly uneasy as the credits rolled and the VCR clicked off. It's a film that truly gets under your skin.