Okay, slide that tape into the VCR, maybe adjust the tracking just so, and prepare yourself. Because some movies weren't just rented, they were acquired, whispered about, maybe hidden from parents or partners. And few titles from the golden age of Hong Kong cinema buzz with quite the same notorious energy as 1991's Sex and Zen (originally Yuk pui tsuen ji tau ching bou gaan). Forget subtle art-house erotica; this was Category III hitting the mainstream with the force of a comedic tsunami, wrapped in surprisingly lavish period detail.

### From Classic Lit to Cult Sensation

Based, believe it or not, on Li Yu's 17th-century erotic novel The Carnal Prayer Mat, the film takes a decidedly less philosophical and infinitely more cartoonish approach to its source material. We follow the smug scholar Mei Yeung-Sheng (Lawrence Ng, bringing a certain naive arrogance to the role) who, convinced his intellectual prowess is matched only by his... well, physical prowess, embarks on a quest for ultimate sexual enlightenment. This journey, naturally, involves bedding as many women as possible and, in one of the film's most infamous sequences, seeking out a rather unorthodox surgical enhancement involving a horse. Yes, really.

This wasn't some cheap, shot-in-a-week exploitation flick, though. Directed by Michael Mak (brother of the equally boundary-pushing producer Johnny Mak), Sex and Zen had surprisingly high production values for its Category III rating. The sets are often elaborate, the costumes vibrant, recalling the look of more 'respectable' historical martial arts epics of the time. This visual polish creates a bizarre but undeniably entertaining contrast with the often juvenile, slapstick humour and explicit sexual situations. It’s a film that looks like it cost a pretty penny, and it did – relatively speaking for its genre. It famously became the highest-grossing Category III film in Hong Kong history up to that point, raking in over HK$18 million, a testament to its unique, if controversial, appeal.

### The Amy Yip Factor and Outrageous Set Pieces

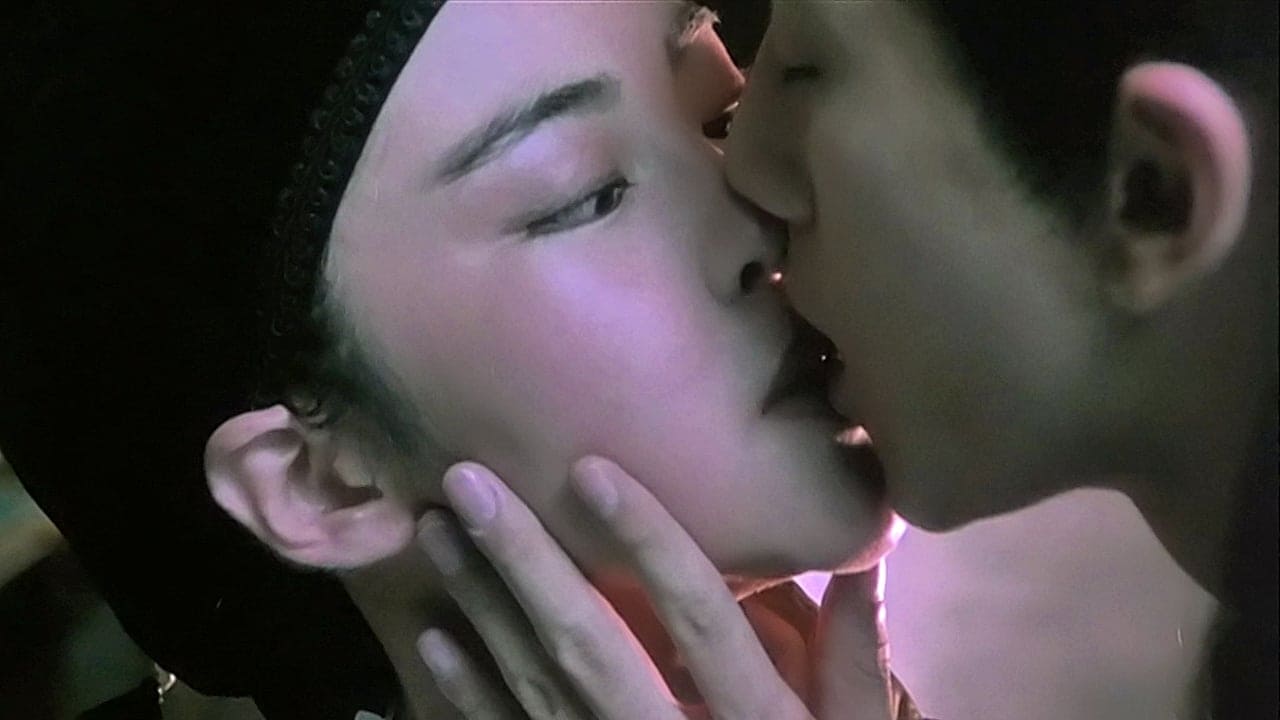

You can't discuss Sex and Zen without mentioning Amy Yip. Already a major star known for her voluptuous figure, this film cemented her legendary status. Playing Huk-Yeung, the initially reserved wife whose desires are eventually awakened (and then some), Yip became inextricably linked with the film's success. Rumours famously swirled that her breasts were insured for a significant sum by the production, a fantastic bit of retro fun fact marketing genius, whether strictly true or not. She, along with the formidable Kent Cheng (often seen in more serious cop roles, like in Crime Story (1993) alongside Jackie Chan) as the lusty thief Chua Yan, leans into the film’s comedic excess with gusto.

The "action," such as it is, isn't about gunfire or explosions, but about the sheer audacity of the scenarios. The film throws everything at the screen – elaborate seductions, comical misunderstandings, Daoist sexual techniques presented with maximum visual flair, and yes, that infamous transplant scene. It’s all staged with a certain frantic energy, closer to a live-action cartoon than anything resembling realism. Watching it now, you appreciate the commitment – this was pre-CGI enhancement, relying on clever editing, prosthetic work (of varying quality!), and the performers' willingness to embrace the absurdity. There's a raw, unpolished energy to its explicitness that feels distinctly of its time, worlds away from today's often sterile or overly serious depictions. Remember how shocking, yet strangely funny, some of those moments felt on a fuzzy VHS copy late at night?

### More Than Just Skin?

Beneath the relentless barrage of T&A and lowbrow gags, the film does retain a sliver of the original novel's cautionary theme about lust leading to ruin. Mei Yeung-Sheng's journey isn't exactly portrayed as aspirational in the end. But let's be honest, deep philosophical insights aren't why this tape flew off rental shelves (often from under the counter). It was the promise of taboo-breaking spectacle, delivered with a uniquely Hong Kong blend of high energy, broad comedy, and historical fantasy.

Its success inevitably spawned sequels (Sex and Zen II, Sex and Zen III) and countless imitators throughout the 90s, solidifying the Category III genre's place in Hong Kong cinema history. For many Western viewers discovering Hong Kong cinema via bootleg tapes or Chinatown video stores, Sex and Zen was an unforgettable, eye-opening experience – a glimpse into a cinematic world operating under entirely different rules.

---

VHS Heaven Rating: 7/10

Justification: While undeniably crude, often silly, and certainly not high art, Sex and Zen earns its points for sheer audacity, surprisingly high production values for its genre niche, its landmark status in Hong Kong cinema history, and the unforgettable performances (especially from Amy Yip). It fully commits to its bizarre premise with infectious energy. It loses points for the sometimes grating humour and the fact that its shock value, while potent in '91, has inevitably faded, leaving the silliness more exposed.

Final Take: A quintessential artifact of the Hong Kong Category III boom – loud, lewd, and strangely lavish. It's a historical curiosity that’s still surprisingly entertaining, provided you know exactly what kind of ride you're signing up for. Lock the doors, dim the lights, and maybe don't watch it with your grandparents.