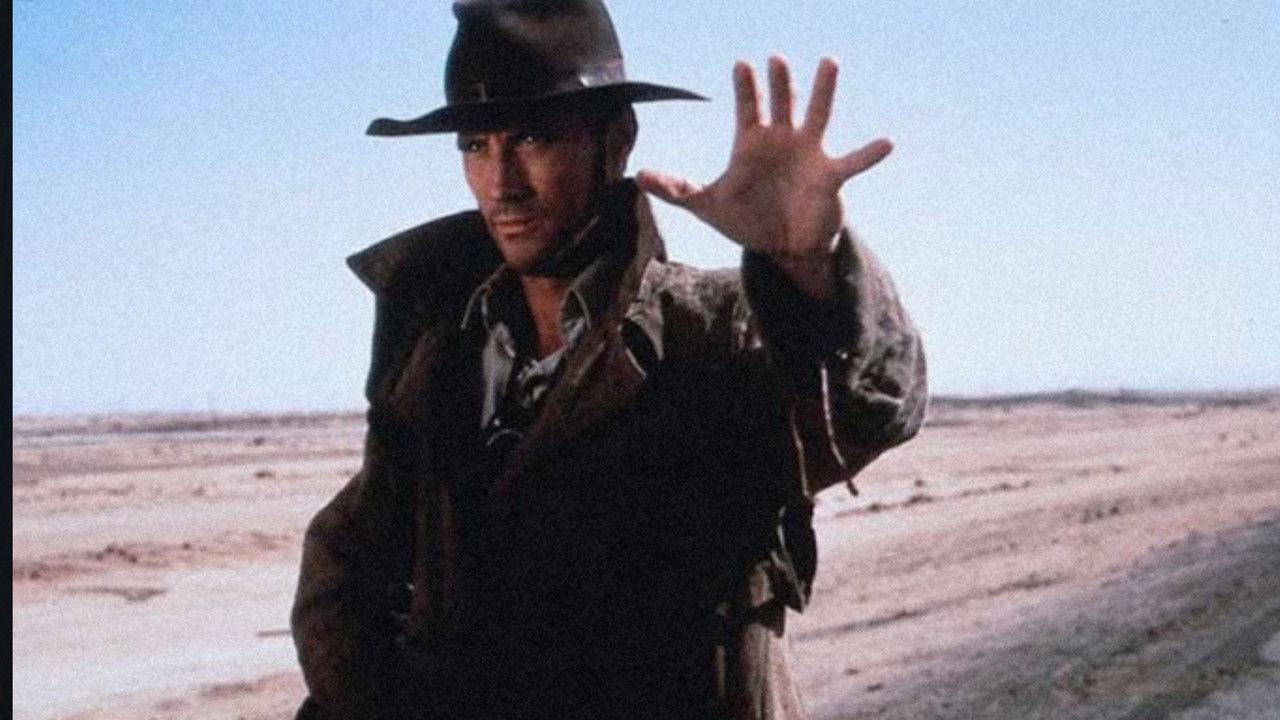

The heat shimmers off the asphalt, distorting the endless horizon of the Namibian desert into a wavering mirage. It’s a landscape bleached by the sun, ancient and unforgiving, where the wind whispers forgotten tales and something malevolent drifts on the desolate air. This isn't just the setting for Richard Stanley’s ill-fated masterpiece, Dust Devil (1992); it's the film's very soul – a tangible presence that seeps into every frame, promising isolation and a dread as old as the dunes themselves. Forget jump scares; this is the kind of film that settles under your skin, a slow burn that leaves you feeling exposed and vulnerable long after the tape has sputtered to a stop.

A Shape in the Heat Haze

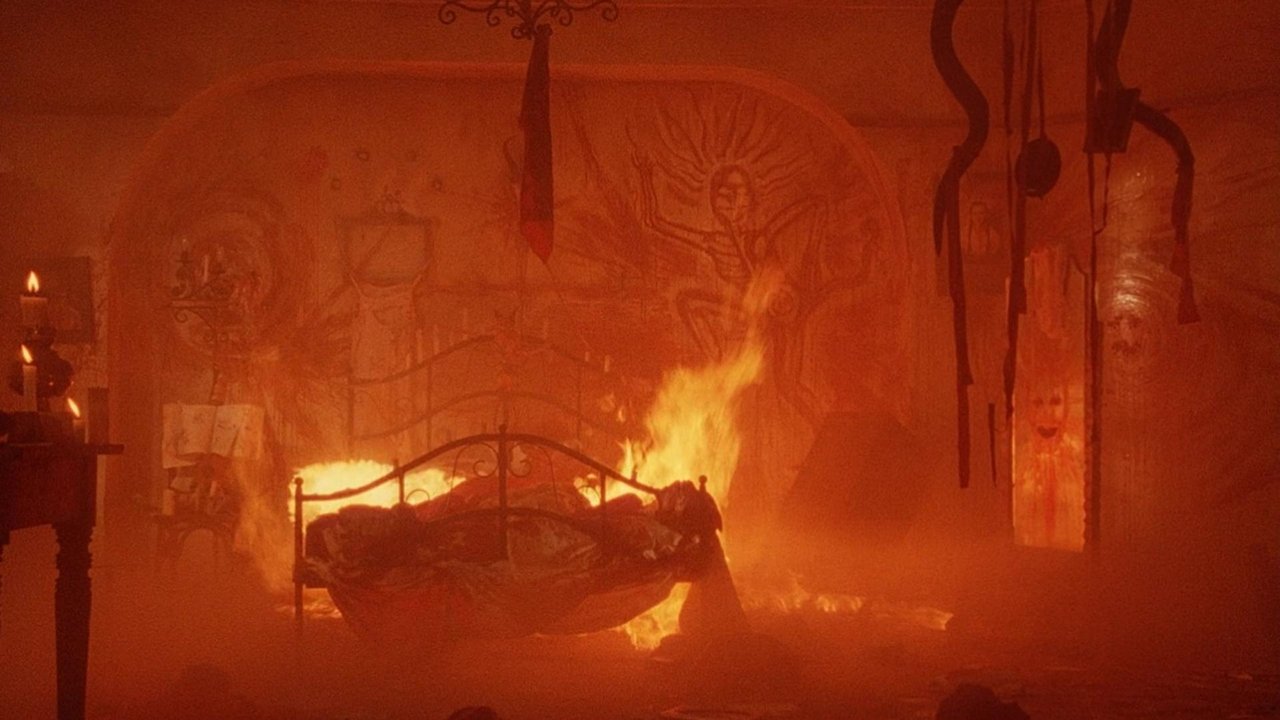

At its core, Dust Devil is deceptively simple: a nameless, enigmatic hitchhiker (Robert John Burke) drifts through the newly independent Namibia, leaving a trail of ritually murdered bodies in his wake. He is the Dust Devil, a supernatural entity feeding on the despair of those who have lost their way. Into this arid nightmare drives Wendy (Chelsea Field), escaping a suffocating marriage and inadvertently heading towards a collision course with the killer. Pursuing them both is Ben Mukurob (Zakes Mokae), a weary detective haunted by his past and steeped in the local folklore that recognizes the true nature of the evil he hunts. What unfolds is less a conventional slasher and more a hallucinatory journey into mysticism, madness, and the crushing weight of the desert landscape.

Forged in Fire and Frustration

Watching Dust Devil today, especially if you managed to track down the elusive Director's Cut (or the later 'Final Cut') that often felt like whispered legend among VHS traders back in the day, is to witness a singular, fiercely personal vision wrestling against near-impossible odds. Richard Stanley, who had burst onto the scene with the cyberpunk cult hit Hardware (1990), poured his fascination with South African mythology and extensive research into local legends (specifically the 'Nain-se-loop' or 'finger walker' tales, intertwined with a real-life serial killer case he investigated) into the script. Filming on location in the vast, stark beauty of Namibia presented immense logistical challenges, further compounded by severe financial difficulties and infamous studio interference from distributors like Miramax, who drastically recut the film for certain markets, leaving Stanley’s original intent fractured. It's a miracle the film exists at all, and perhaps that troubled birth imbues it with an extra layer of haunted authenticity. The struggle feels baked into the celluloid. Remember hearing whispers about the 'lost' footage? That pursuit became part of the film's own mythos for collectors.

Desert Ghosts and Desperate Souls

Robert John Burke, who stepped in after Richard Lynch reportedly departed the project, delivers a performance of chilling stillness. His Dust Devil isn't a cackling monster but an empty vessel, a void given human form. His calm detachment as he performs his gruesome rituals is far more disturbing than any amount of scenery-chewing could be. Chelsea Field, perhaps best known Stateside for roles like The Last Boy Scout (1991), provides the film's human anchor, her journey from suburban desperation to existential terror feeling palpable. But it's the legendary South African actor Zakes Mokae (unforgettable in Wes Craven's The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988)) who truly grounds the film's supernatural elements. His Mukurob is a man caught between worlds, the modern investigator forced to confront ancient, inconvenient truths. His performance lends the mythology profound weight and weary dignity.

A Symphony of Dust and Dread

Stanley’s direction, when allowed its full scope, is hypnotic. He wields the Namibian landscape like another character – vast, beautiful, and utterly indifferent to human suffering. The cinematography captures both the epic scale and the intimate, sun-scorched details with painterly precision. Complementing the visuals is Simon Boswell’s incredible score, a haunting blend of tribal rhythms, synthesized dread, and Ennio Morricone-esque grandeur. It’s a soundtrack that perfectly encapsulates the film's unique fusion of Western, horror, and ethnographic dreamscape. The pacing is deliberate, meditative even, building atmosphere through suggestion and implication rather than cheap thrills. Doesn't that desolate, wind-swept score still echo long after viewing?

Legacy in the Wasteland

Dust Devil was never destined for mainstream success. Its art-house sensibilities, challenging themes, and fractured release history relegated it to cult status almost immediately. Yet, for those who sought it out on worn VHS tapes or later, restored DVD/Blu-ray editions, it offered something unique: a horror film that felt genuinely other, steeped in a specific cultural context often ignored by Western genre filmmaking. It wasn't just scary; it was transporting, unsettling in a way that lingered. It’s a film that feels both deeply personal to its creator and eerily universal in its exploration of despair, belief, and the dark spaces on the map.

VHS Heaven Rating: 8/10

Dust Devil earns a strong 8 out of 10. While its troubled production undeniably led to some narrative fragmentation (particularly in lesser cuts) and its deliberate pace might test impatient viewers, its staggering atmospheric power, unique blend of genres, haunting performances (especially Mokae), unforgettable score, and sheer visual poetry make it a standout piece of 90s cult cinema. The Director's/Final Cut, representing Stanley's intended vision, is a near-masterpiece of mood and mythological horror. Its flaws are intrinsically linked to its fascinating, turbulent creation story, making it even more compelling for connoisseurs of cinematic survivors.

It remains a potent reminder that sometimes the most resonant horror doesn't leap out from the shadows, but drifts in on the wind, under a relentless sun, whispering of terrors far older than flickering electric lights.