It arrives like a bootleg transmission, grainy and stark black-and-white, whispering forbidden truths. There's no fanfare, no soaring score, just the chillingly mundane setup: a documentary crew is following a serial killer named Ben, chronicling his life, his philosophy, and his horrifying work. Man Bites Dog (C'est arrivé près de chez vous, 1992) wasn't just another edgy indie flick slipped onto the video store shelf; it felt like something smuggled, something dangerous. Watching it back then, perhaps late at night on a flickering CRT, felt like becoming an accomplice.

Meet Ben, Your Charming Monster

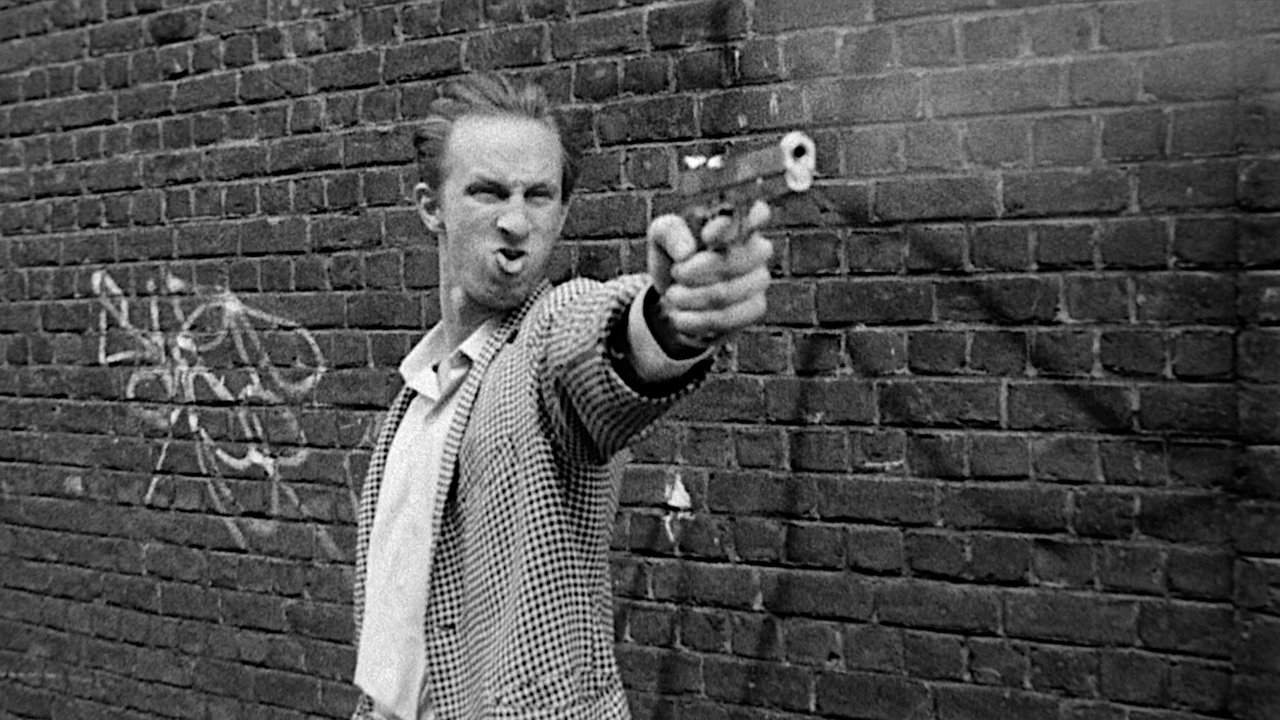

At the heart of the film's corrosive power is Benoît Poelvoorde's terrifyingly charismatic performance as Ben. This isn't your silent, masked slasher. Ben is loquacious, opinionated, almost likable in his strangely poetic musings on architecture, classical music, and the socio-economic practicalities of murder. He dispenses racist, sexist, and homophobic bile with the same casual air he uses to discuss the best way to dispose of a body (ballast weight is key, apparently). Poelvoorde, in a role that would launch his career in French-language cinema, doesn't just play a killer; he embodies a narcissistic void disguised as a bon vivant. He draws you in with his wit even as his actions repel, forcing a deeply uncomfortable intimacy. It's a performance that burns itself into your memory, long after the tape hiss fades.

The Camera Never Lies... Or Does It?

Shot on a shoestring budget (reportedly around $20,000, scraped together by the filmmakers), the film’s raw, handheld, cinéma vérité style is utterly convincing. This wasn't just an aesthetic choice; it was partly born of necessity by the directing trio of Rémy Belvaux, André Bonzel, and Benoît Poelvoorde himself – recent film school graduates pouring everything into this audacious project. Belvaux and Bonzel even play members of the increasingly compromised film crew, blurring the lines behind and in front of the camera. The grainy 16mm film stock doesn't just feel dated; it enhances the grim authenticity, making the violence feel less staged and more like found footage dredged from somewhere awful. This gritty realism was key to the film's power – it didn't look like a glossy Hollywood production, making its horrors feel disturbingly plausible in the pre-digital era.

Descent into the Abyss

What begins as a morbidly fascinating, albeit pitch-black, satire on media obsession and violence slowly curdles into something far more disturbing. The initial "professional" distance of the documentary crew – led by director Rémy (Rémy Belvaux) and cameraman André (André Bonzel) – gradually erodes. They start by simply observing Ben's crimes, passively recording his brutal killings of pensioners, postal workers, and random families. But soon, starved for funding and perhaps seduced by Ben's warped charisma (or simply numbed into nihilism), they become active participants. They help dispose of bodies, join in on home invasions, and ultimately, their camera becomes a weapon in its own right. This descent is the film's true masterstroke – it implicates not just the fictional crew, but us, the viewers. How long can we watch before we too feel complicit? Did that slow slide into active participation genuinely shock you back then? It certainly left a mark.

The film courted immediate controversy upon its release, famously causing walkouts (and yet winning awards) at the Cannes Film Festival. It secured the dreaded NC-17 rating in the US, limiting its theatrical run but cementing its cult status on VHS among adventurous viewers seeking something truly transgressive. This wasn't Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986) with its bleak, observational dread; Man Bites Dog used satire and jet-black humour as a horrifying Trojan horse, smuggling its nihilistic commentary past your defences before twisting the knife.

The Lingering Stain

Man Bites Dog is not an easy watch. It's brutal, often repellent, and its humour is darker than a coal mine at midnight. Its depiction of violence, including a truly harrowing sexual assault sequence that pushes the boundaries of exploitation and commentary, remains deeply unsettling. Yet, its power is undeniable. It functions as a savage critique of media sensationalism, viewer apathy, and the seductive nature of violence itself. The filmmakers, barely out of school, crafted something raw, audacious, and unforgettable – a Molotov cocktail thrown into the art house scene. The fact that they achieved this with such limited resources, essentially willing the film into existence through sheer provocative will, is part of its grungy legend. Does its low-fi aesthetic still feel unnerving, precisely because it lacks Hollywood polish?

Its influence can arguably be seen in the later wave of mockumentaries and found-footage films, though few have dared to match its nihilistic bite or confrontational stance. It remains a singular, scarring artifact of early 90s indie cinema.

VHS Heaven Rating: 8/10

Justification: Man Bites Dog earns its high score through its sheer audacity, Benoît Poelvoorde's landmark performance, and its chillingly effective mockumentary execution. It’s a masterclass in black comedy that pushes satire to its absolute breaking point. The low budget becomes a strength, enhancing the grim realism. While the extreme content makes it difficult to universally recommend, its filmmaking craft, fearless commentary, and lasting impact as a cult phenomenon are undeniable. It loses points only for the sheer extremity that can tip into feeling gratuitous for some viewers, potentially overshadowing its satirical intent at moments.

Final Thought: This is one of those tapes you might have hesitated to return to the video store, feeling like you possessed something illicit. Man Bites Dog doesn't just show you the abyss; it makes you question why you were looking in the first place. A truly unforgettable, if deeply uncomfortable, piece of VHS history.