Okay, settle in, pop that tape in the VCR (mentally, at least), and let the tracking sort itself out. Some films hit you with a quiet contemplation, others with blockbuster bombast. And then there are films like Love and a .45 (1994) – the cinematic equivalent of a shot of cheap whiskey chased with a stick of dynamite, leaving you buzzing with a strange mix of exhilaration and unease. It’s one of those mid-90s slices of indie filmmaking that felt beamed in from a slightly grungier, more desperate dimension, sitting there on the video store shelf promising chaos and maybe, just maybe, a twisted kind of heart.

Texas Heat and Trigger Fingers

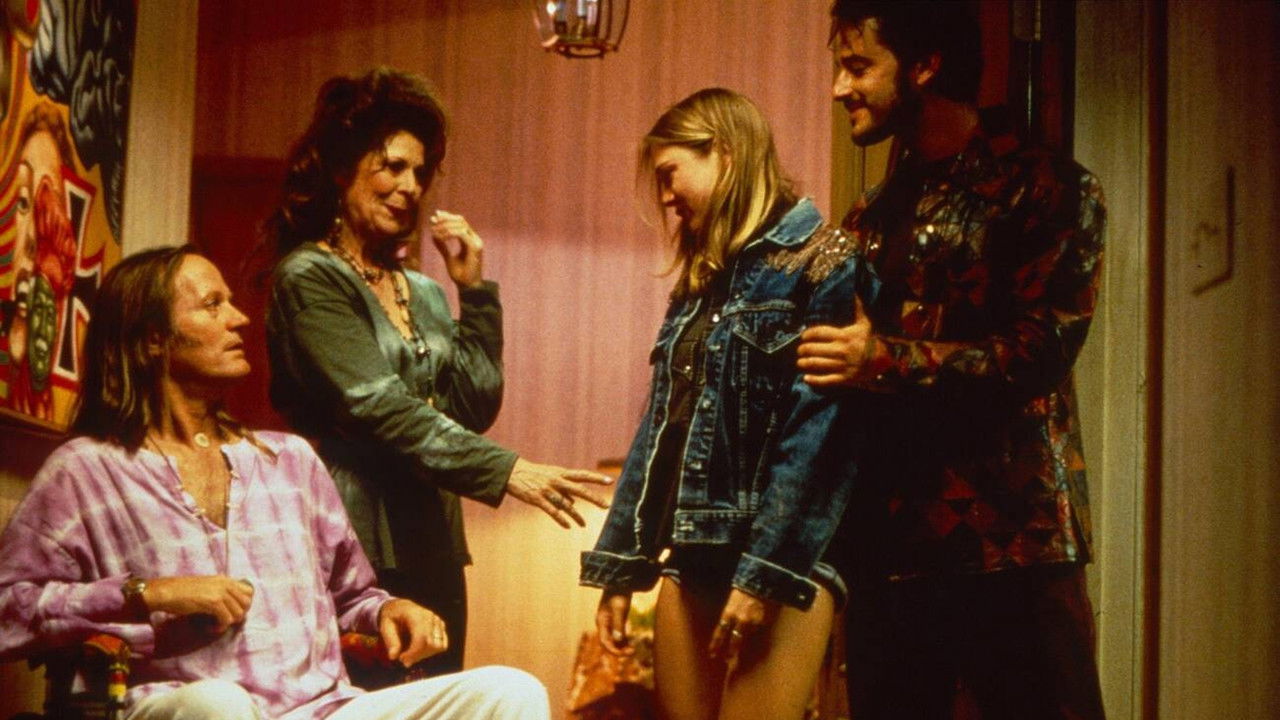

At its core, this is a lovers-on-the-run story, a well-worn genre trope. Watty (Gil Bellows) is a small-time convenience store robber with vague dreams of Mexico and a slightly skewed moral compass. His girlfriend, Starlene (Renée Zellweger), shares those dreams, clinging to him with a fierce loyalty that feels both naive and surprisingly steadfast. Their relatively simple plan – one last score, then south of the border – goes violently sideways thanks to Watty’s loose-cannon partner, Billy Mack Black (Rory Cochrane). What follows is a desperate flight across the sun-baked Texas landscape, with psychotic Billy, loan sharks, and the law hot on their trail. Director/writer C.M. Talkington, in what remains his sole feature film directorial credit, crafts a world that feels simultaneously heightened and grounded in a certain kind of Texan desperation.

Sparks Fly: Watty and Starlene

What elevates Love and a .45 beyond a simple Bonnie and Clyde riff is the undeniable chemistry between its leads. Gil Bellows, perhaps best known to many from The Shawshank Redemption released the same year, brings a kind of laid-back, almost accidental charm to Watty. He’s no criminal mastermind, just a guy trying to get by, propelled by circumstance and a genuine affection for Starlene. You believe him when he says he doesn't want to hurt anyone, even as the body count inevitably rises.

And then there’s Renée Zellweger. Watching this now, knowing the massive stardom that awaited her just a couple of years later with Jerry Maguire (1996), is fascinating. Here, the vulnerability is palpable, but it’s laced with a steely resolve. Starlene isn't just along for the ride; she's an active participant, her devotion to Watty absolute. Zellweger makes Starlene feel real – flawed, scared, but utterly committed. There's a scene involving a confession in a photo booth that manages to be incredibly tender amidst the surrounding mayhem, largely thanks to the authenticity she brings. It’s a performance that hinted strongly at the powerhouse she would become.

The Hurricane Named Billy

Let's be honest, though: a huge part of the film’s visceral impact comes from Rory Cochrane as Billy Mack Black. Fresh off playing the perpetually stoned Slater in Dazed and Confused (1993), Cochrane absolutely transforms here into a terrifying force of nature. Billy is pure, unadulterated id – drug-fueled, pathologically violent, and utterly unpredictable. His pursuit of Watty and Starlene provides the film's primary engine of suspense, and Cochrane dives into the role with a terrifying glee that borders on the cartoonish but never quite crosses the line, remaining genuinely menacing. He’s the chaotic grit in the oyster, the element that ensures this particular road trip is paved with blood and bullets.

Style, Grit, and That 90s Sound

C.M. Talkington, drawing inspiration from his Texas roots and reportedly from people he knew, infuses the film with a distinct visual style. It's less slick than Tarantino's True Romance (1993) or Stone's Natural Born Killers (1994), feeling rougher around the edges, more indebted to exploitation flicks and rock 'n' roll energy. The soundtrack, a killer mix of alternative rock, punk, and country (think The Jesus and Mary Chain rubbing shoulders with Johnny Cash), is practically a character itself, perfectly capturing the film’s restless, rebellious spirit. Filmed on location in Texas on what was clearly a tight budget (rumored to be under $1 million), the movie makes a virtue of its limitations, achieving a dusty, lived-in feel that enhances its authenticity. It wasn't a huge box office hit, finding its devoted audience, like so many gems of the era, through VHS rentals and word-of-mouth – a true cult classic nurtured in the aisles of video stores.

More Than Just Mayhem?

Amidst the gunfire and screeching tires, the film asks some uncomfortable questions. Can love truly conquer all, even when “all” includes psychotic ex-partners and escalating felonies? What does it mean to be famous, or infamous, when the media briefly turns Watty and Starlene into fleeting folk heroes? It doesn’t offer easy answers, preferring to let the ambiguity hang in the hot Texas air. There’s a strange sort of romanticism woven into the violence, a belief in the central relationship that feels almost defiant against the grim reality closing in. Does this romantic vision entirely hold up under scrutiny? Perhaps not, but its commitment is compelling.

I remember renting this one, drawn in by the lurid cover art and the promise of something edgy. It delivered on that promise, but also surprised me with its unexpected heart. It felt dangerous, vital, and unapologetically cool in that specific mid-90s way.

Rating: 8/10

Love and a .45 is a potent cocktail of violence, romance, and dark humor, fueled by terrific performances – particularly from a pre-superstardom Zellweger and a terrifying Cochrane. Its indie grit, stylish direction (for a one-and-done director, Talkington showed real promise), and killer soundtrack make it a standout example of 90s crime cinema. While it might lean heavily on genre conventions and its romantic core occasionally strains against the brutality, its raw energy and unwavering commitment to its doomed lovers make it a ride absolutely worth taking again on VHS (or your format of choice). It lingers, not just for the shocks, but for that defiant spark of love flashing in the muzzle flare. What truly lasts longer – the love, or the .45? The film leaves you pondering that long after the tape clicks off.