There’s a certain kind of heat that radiates off the screen in Spike Lee’s Clockers (1995), and it’s not just the simmering Brooklyn summer. It’s the heat of pressure, of desperation, of dwindling options in a world that feels simultaneously vast and suffocatingly small. Watching it again, decades after first sliding that well-worn VHS tape into the VCR, the film’s opening montage – stark, graphic police photos of murder victims – still serves as a brutal, unflinching statement: this isn't going to be an easy ride.

Beneath the Bleachers

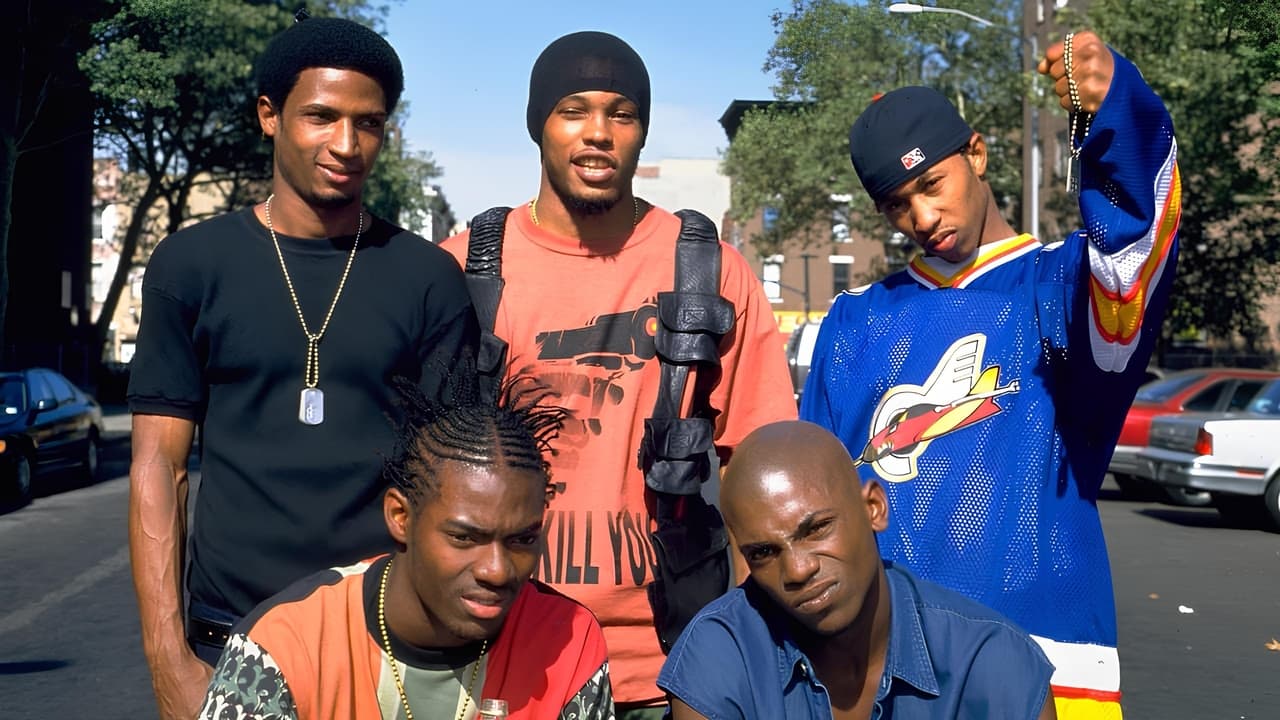

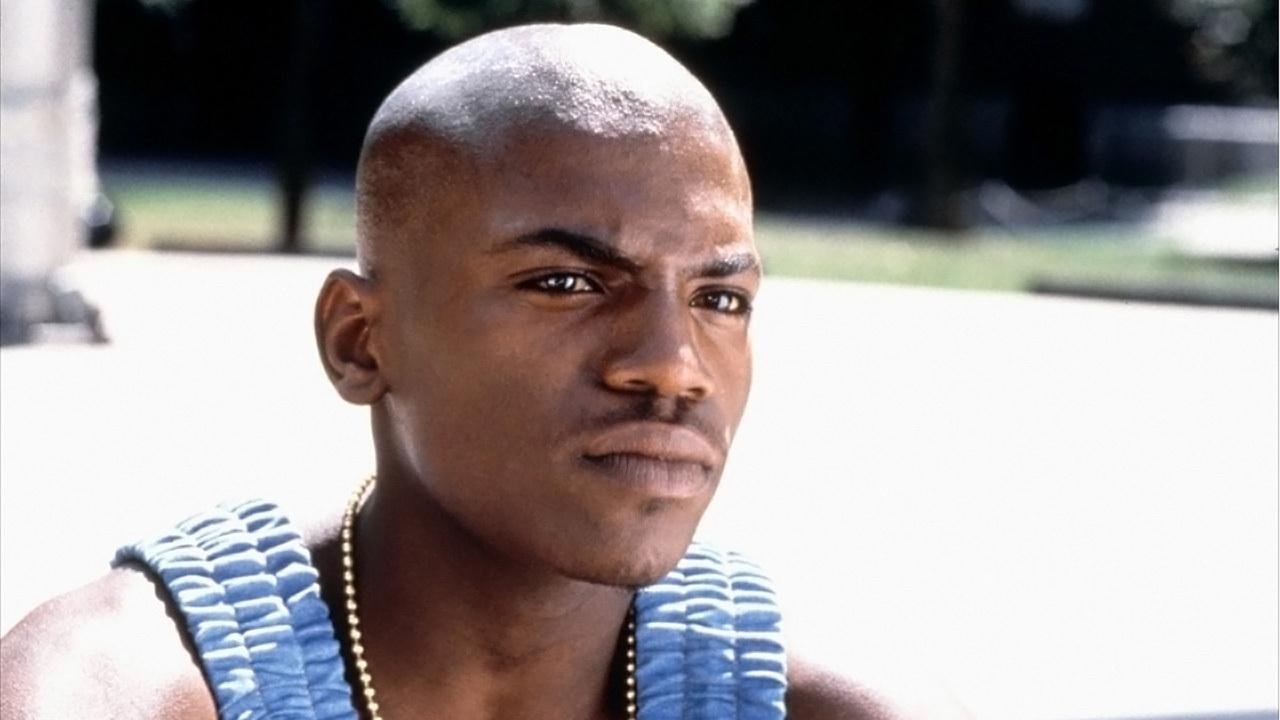

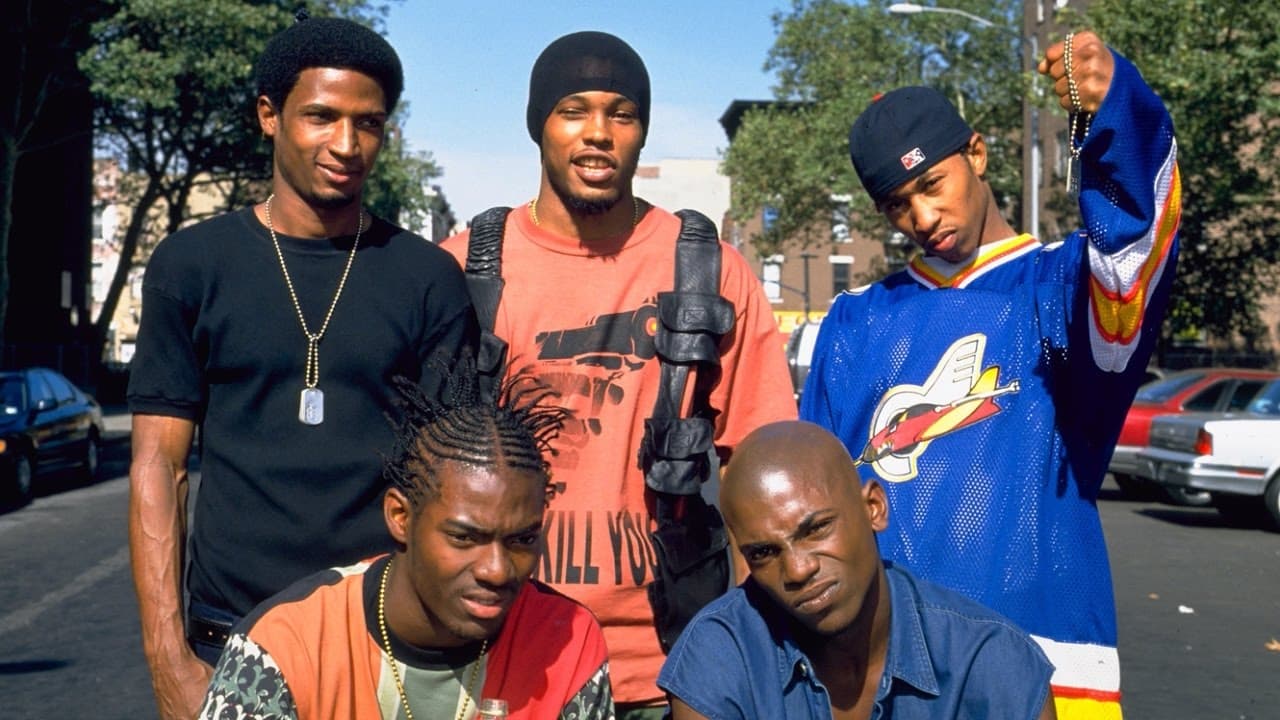

At the heart of this dense, atmospheric 90s crime drama is Strike (Mekhi Phifer in a remarkable debut), a young, ulcer-plagued drug dealer – a ‘clocker’ – working the benches outside the Gowanus housing projects. He’s ambitious, dreaming of escape, but deeply entangled in the web spun by his mentor and supplier, the imposing Rodney Little (Delroy Lindo). Rodney is all paternal smiles and chilling threats, a father figure carved from pure menace. When a rival dealer turns up dead, Strike finds himself caught in the crosshairs of Rodney’s expectations and the dogged investigation of homicide detective Rocco Klein (Harvey Keitel). The situation spirals when Strike’s responsible older brother, Victor (Isaiah Washington), confesses to the crime – a confession that rings hollow to Klein’s cynical ears.

The Weight of Walls

What elevates Clockers beyond a standard police procedural is its profound sense of place. Lee, working from the novel by Richard Price (who also co-wrote the screenplay), makes the projects more than just a setting; they are a character, a force field dictating the lives within. The film breathes the air of these streets, the constant observation, the lack of privacy, the feeling of being perpetually watched, judged, and cornered. Cinematographer Malik Hassan Sayeed captures this with a gritty, desaturated look, occasionally punctuated by stylistic flourishes – like Strike seeming to levitate during moments of intense stress – that visually underscore the psychological burden. Lee’s decision to film extensively within the actual Brooklyn projects lends an undeniable, almost documentary-like authenticity, grounding the drama in a harsh reality. You can almost feel the cracked pavement under your feet, hear the distant sirens that never seem to stop.

Faces in the Crowd

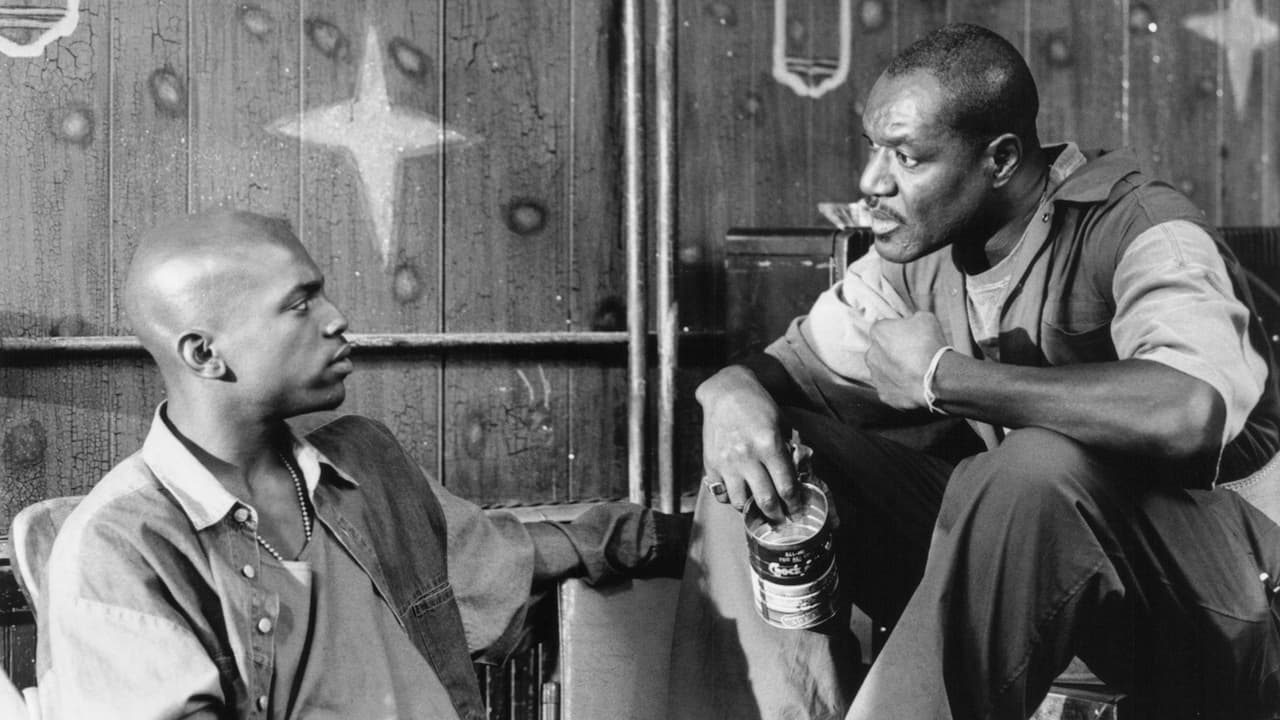

The performances here are simply outstanding, anchoring the film’s emotional weight. Mekhi Phifer, barely out of his teens, carries the film with a vulnerability that’s heartbreaking. His Strike isn't a hardened gangster; he’s a kid drowning, clutching at straws, his ambition poisoned by fear and a gnawing stomach ailment that feels like the physical manifestation of his trapped existence. Opposite him, Delroy Lindo delivers a career-defining performance as Rodney. It’s a masterclass in quiet terror. Rodney’s power isn’t just in violence, but in his psychological manipulation, his ability to offer opportunity with one hand while tightening the leash with the other. His calm, measured delivery makes his sudden flashes of brutality all the more shocking.

And then there’s Harvey Keitel as Rocco Klein. He’s weary, seen-it-all, operating within a system he knows is flawed. Keitel plays him not as a hero, but as a man doing a grim job, pushing suspects, looking for the angle, yet retaining a flicker of something that might pass for conscience, particularly in his interactions with Strike. His scenes with his partner, Larry Mazilli, played with characteristic energy by John Turturro, provide brief moments of weary camaraderie amidst the grimness.

Adapting the Source, Sharpening the Focus

It’s worth remembering that this project initially had Martin Scorsese attached to direct, with author Richard Price envisioning Robert De Niro playing Klein. When Scorsese moved on to Casino (1995), he suggested Spike Lee, a fascinating transition that undoubtedly shifted the film's perspective. While Price's novel delves deep into the procedural aspects from Klein's viewpoint, Lee, while respecting the source material (keeping Price on as co-writer was key), subtly foregrounds the systemic issues, the social environment, and the agonizing lack of choices facing young Black men like Strike. This wasn't just about who pulled the trigger; it was about the world that loaded the gun and put it in their hands. The film didn’t shy away from the harsh realities, contributing perhaps to its modest box office performance – grossing only about $13 million against a $25 million budget. It wasn't the kind of crime story designed for easy consumption.

Echoes in the Present

Watching Clockers today, its themes feel depressingly relevant. The cycle of poverty and crime, the allure and danger of the streets, the often-adversarial relationship between law enforcement and marginalized communities – these issues haven't faded. Lee refuses easy answers or neat resolutions. The film leaves you with a knot in your stomach, questioning the nature of responsibility, the meaning of justice in an unjust system, and the crushing weight of circumstance. What choices did Strike truly have? What future awaits him, even if he clears his name? The film doesn't offer comfort, only a stark, compelling portrait of lives lived on the edge. The potent soundtrack, brimming with 90s East Coast hip-hop, further cements its time and place, acting almost as a Greek chorus commenting on the unfolding tragedy.

Rating: 8.5/10

Clockers is a demanding, powerful piece of 90s filmmaking. It’s anchored by unforgettable performances, particularly from Phifer and Lindo, and brought to life by Spike Lee's distinctive vision and unwavering gaze. While perhaps less celebrated than some of Lee's other joints, its atmospheric intensity, moral complexity, and unflinching social commentary earn it a significant place on the shelf. It’s a film that doesn't just entertain; it gets under your skin and stays there, a haunting reminder from the VHS era of stories that needed telling, however uncomfortable. It leaves you pondering not just the mystery within the film, but the larger societal puzzles that endure long after the tape stops rolling.