What is truth? Is it an objective reality, or merely the version of events we choose—or are forced—to believe? 1997's twisty thriller Deceiver throws this question under the harsh, unforgiving lights of an interrogation room and spends its runtime dissecting the fragile, often self-serving nature of human testimony. Released in some territories under the more direct title Liar, this film arrived near the tail end of the VHS boom, a tightly wound psychological piece that perhaps got lost amidst the bigger blockbusters but rewards rediscovery on a quiet evening. It’s the kind of film you might have stumbled upon in the 'New Releases' section, drawn in by the intense cover art featuring Tim Roth, Chris Penn, and Michael Rooker.

Under Pressure

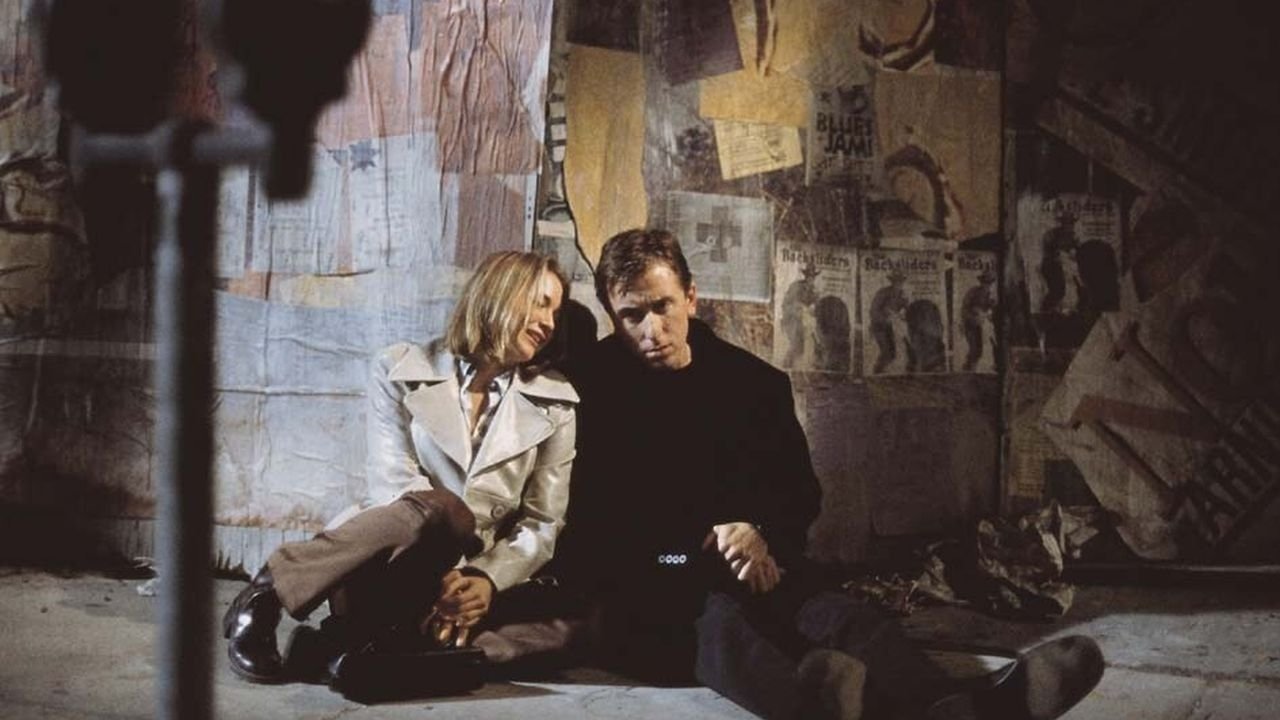

The setup is deceptively simple: James Walter Wayland (Tim Roth), an intelligent, epileptic, and immensely wealthy Princeton graduate with a penchant for erratic behaviour and philosophical musings, is the prime suspect in the grisly murder of a prostitute found bisected in a park. Detectives Braxton (Chris Penn) and Kennesaw (Michael Rooker) haul him in for questioning, strapping him to a polygraph machine operated by the ostensibly neutral Mook (Ellen Burstyn, adding gravitas). What unfolds is less a straightforward procedural and more a claustrophobic stage play, a battle of wills drenched in sweat, suspicion, and shifting narratives. The Pate brothers, Jonas and Josh, making their feature directorial debut here, wisely keep the focus tight, letting the confines of the interrogation suite amplify the rising tension. You can almost feel the stale air, the hum of the machine, the palpable animosity crackling between the men.

A Triangle of Tension

The film rests squarely on the shoulders of its central trio, and they deliver performances simmering with intensity. Tim Roth is captivating as Wayland. Is he a brilliant manipulator toying with the detectives? A damaged soul genuinely struggling with memory lapses and addiction? Or a cold-blooded killer hiding in plain sight? Roth plays all these possibilities simultaneously, his performance a masterclass in ambiguity. He shifts from vulnerable to arrogant, from philosophical detachment to raw panic, often within the same breath. It’s a performance that keeps you guessing long after the credits roll.

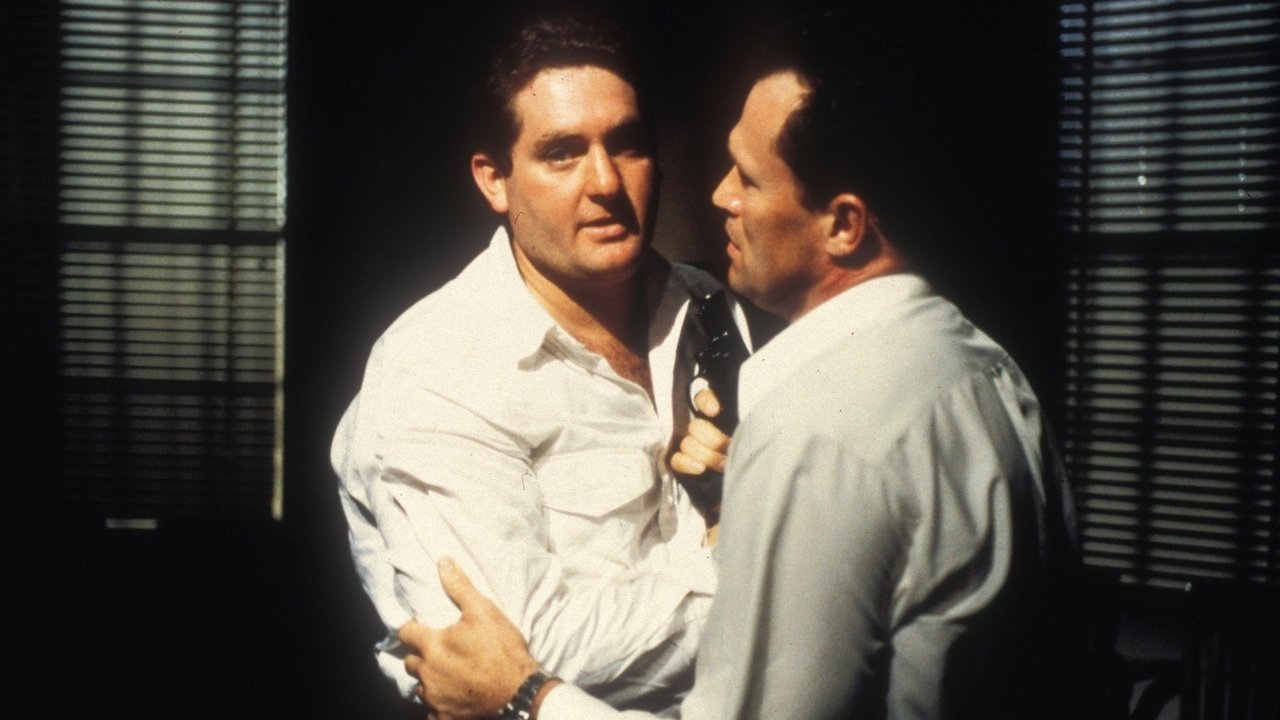

Facing him are Chris Penn as Braxton and Michael Rooker as Kennesaw. Penn, radiating a barely contained volcanic rage fueled by personal demons and a gambling problem, is the volatile ‘bad cop’. His explosive frustration feels frighteningly real. Rooker, weary and cynical, provides the ‘good cop’ counterpoint, though his methods are hardly gentle. It’s fascinating to see these two actors, who shared the screen so memorably in Reservoir Dogs (1992), spar again, bringing a different but equally potent energy to their dynamic here. Their shared history adds an unspoken layer to their interactions – a sense of weary familiarity mixed with deep-seated friction. Burstyn, though having less screen time, offers a crucial anchor of weary professionalism, observing the escalating psychological warfare with a quiet intensity.

Weaving the Web

Deceiver isn't just about finding the killer; it's about how interrogation itself can distort reality. As Wayland recounts his version of events, often contradicting himself or offering provocative alternative theories, the film uses flashbacks that visualize his (potentially unreliable) narratives. The lines blur between objective truth, deliberate lies, and the subjective filters of memory and trauma. The detectives, far from being impartial seekers of truth, bring their own considerable baggage and biases into the room, twisting Wayland's words to fit their preconceived notions. Doesn't this reflect something unsettling about how easily narratives can be manipulated, both by those telling them and those hearing them?

The Pate brothers filmed this primarily in Charleston, South Carolina, and reportedly worked with a modest budget (around $5 million). This constraint likely informed the decision to keep the action largely contained, a choice that becomes one of the film's greatest strengths, forcing the focus onto the dialogue and the actors' faces. Interestingly, the film was originally titled Liar, but faced a name change to Deceiver in the US market to avoid confusion with the Jim Carrey comedy Liar Liar, which also came out in 1997. A small but telling piece of late-90s movie marketing trivia!

Lingering Doubts

Does Deceiver have flaws? Perhaps. Some might find the plot machinations a tad too intricate, the twists occasionally straining credulity. The claustrophobic setting, while effective, can sometimes feel a little stagey. Yet, these are minor quibbles in the face of its core achievements. It's a film that dares to be intelligent, challenging the viewer to constantly reassess what they're seeing and hearing. It doesn't offer easy answers, preferring to leave certain ambiguities hanging in the air. I recall renting this tape, expecting maybe a standard cop thriller, and being genuinely surprised by its depth and the intensity of the performances. It stuck with me, that feeling of being locked in the room with those characters.

Rating: 8/10

Deceiver earns this score through its powerhouse performances, particularly from Roth, Penn, and Rooker, its genuinely claustrophobic atmosphere, and its intelligent exploration of truth, lies, and perception. While some plot mechanics might feel a bit contrived, the sheer psychological tension and the film's refusal to provide easy answers make it a compelling and memorable late-90s thriller. It’s a potent reminder that sometimes the most gripping conflicts are fought not with guns, but with words and the treacherous landscape of the human mind. What truly lingers is the unsettling question: in a room full of deceivers, who can you possibly believe?