It often starts with a single image, doesn't it? That frame that burns itself onto your memory long after the tape has whirred to a stop. For Atom Egoyan’s devastating 1997 masterpiece, The Sweet Hereafter, it might be the sight of a lone school bus against an unforgiving, snow-blanketed Canadian landscape. Or perhaps it’s the haunted eyes of a survivor. Whatever the image, it carries the weight of unspeakable loss, a feeling that permeates every frame of this unforgettable film. This wasn’t a tape you rented for a Friday night thrill; this was one you put in when you were ready to confront something profound, something deeply, achingly human.

A Silence After the Sound

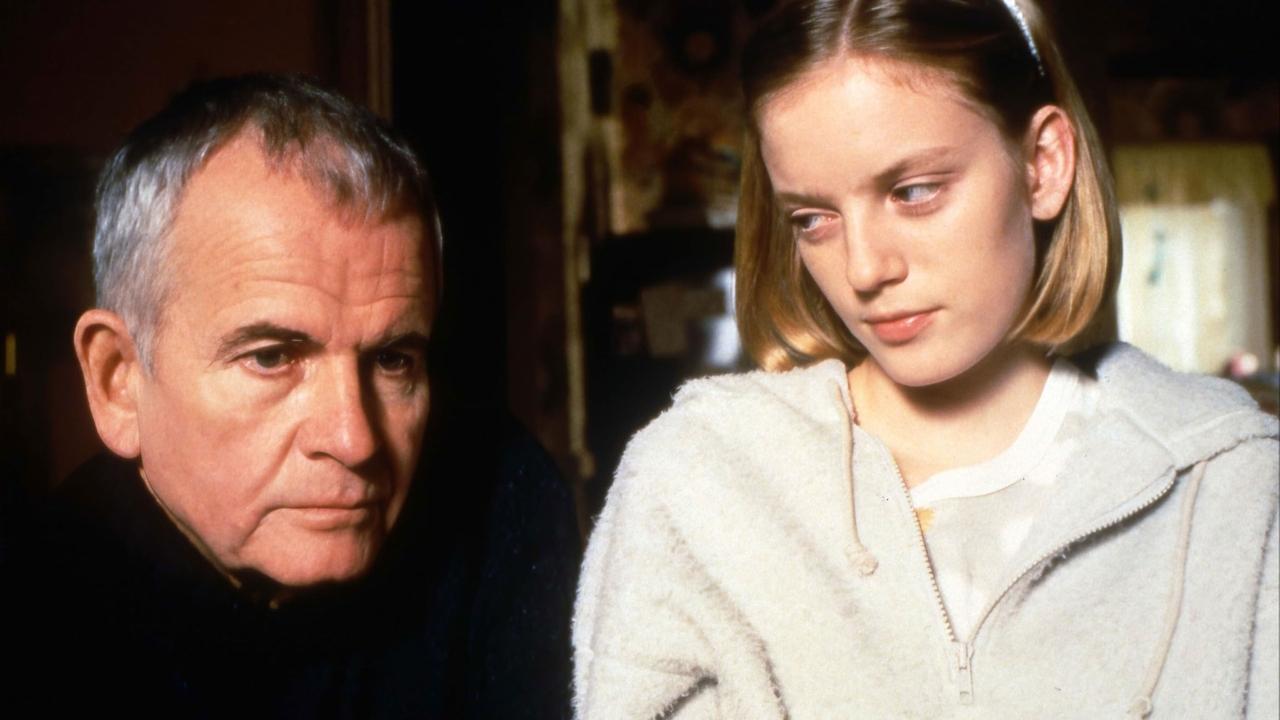

The premise is stark: a horrific school bus accident on an icy road shatters the lives of a small, close-knit community in British Columbia. Into this maelstrom of grief walks Mitchell Stephens (Ian Holm), a big-city lawyer intent on finding negligence, assigning blame, and launching a lucrative class-action lawsuit. He sees a clear narrative, a path to justice (and compensation). But as Egoyan so masterfully reveals, grief rarely follows a straight line, and truth is often far more fractured and elusive than any legal document can capture.

The film, based on the novel by Russell Banks, mirrors this fragmentation in its very structure. Egoyan, who also penned the screenplay, abandons linear storytelling, instead weaving together past and present, perspectives shifting like memories surfacing through trauma. We jump between the time before the accident, the immediate aftermath, and Stephens' interviews with the bereaved parents. This structure isn’t a gimmick; it’s essential. It forces us to piece together the emotional reality of the town, mirroring how the characters themselves grapple with events that defy easy explanation. It reflects the impossibility of simply ‘moving on’ when the very fabric of your reality has been torn.

The Outsider and the Inner Truths

Ian Holm is simply magnificent as Mitchell Stephens. Initially, he seems like the rational outsider, the one who can cut through the emotion. But Egoyan subtly reveals Stephens' own deep-seated pain, particularly concerning his estranged, drug-addicted daughter. His quest for legal clarity becomes intertwined with his personal desperation, a need to impose order on chaos, perhaps because he cannot do so in his own life. It’s a performance layered with weariness, calculation, and a buried vulnerability. It's fascinating to know that Holm stepped into the role after Donald Sutherland had to drop out due to scheduling conflicts; it's hard now to imagine anyone else embodying Stephens' specific blend of professional polish and private anguish.

Opposing Stephens’ drive for a singular narrative are the complex, often contradictory, truths held by the townspeople. We see Billy Ansel (Bruce Greenwood, bringing his characteristic quiet intensity), who was following the bus and witnessed the horror firsthand, grappling with a different kind of guilt. We feel the crushing weight on Dolores Driscoll (Gabrielle Rose), the bus driver who survived but must live with the consequences. And then there are the parents, each navigating a private hell. Egoyan never simplifies their grief; it manifests as anger, denial, numbness, and a desperate search for meaning where none seems readily available.

A Voice That Shatters the Ice

At the heart of the film lies the extraordinary performance of Sarah Polley as Nicole Burnell, a teenager left paralyzed by the crash. Polley, already showing the intelligence and sensitivity that would later define her work as a writer and director (Away from Her, Women Talking), becomes the film's moral center. Initially seen as the star witness for Stephens' case, Nicole carries secrets that complicate the town's narrative of shared innocence. Her testimony, when it finally comes, is shattering – not in its volume, but in its quiet, devastating power. Her haunting fireside performance of Jane Siberry's "One More Colour" becomes an unforgettable expression of buried pain and resilience. Egoyan notably altered the ending from Banks' novel, giving Nicole's character a different, arguably more resonant, form of agency that lands with profound impact.

The Landscape of Loss

Egoyan uses the stark beauty of the British Columbia locations (specifically around Merritt and Spences Bridge) to maximum effect. The snow isn't just scenery; it’s an oppressive presence, muffling sound, isolating the community, mirroring the emotional freeze gripping the characters. Cinematographer Paul Sarossy captures this landscape with a crisp, often chilling, beauty. Adding immeasurably to the atmosphere is the score by Mychael Danna, a frequent Egoyan collaborator. His use of early musical instruments – recorders, viols, crumhorns – creates a soundscape that feels both ancient and immediate, like a medieval lament echoing through the modern tragedy. It’s a choice that underscores the film's engagement with timeless themes, particularly through the recurring motif of the Pied Piper of Hamelin.

The Pied Piper's Shadow

The story of the Pied Piper, read by Nicole to two children before the accident, serves as a powerful, unsettling allegory throughout the film. Who is the piper here? Is it Stephens, leading the town towards a potentially hollow legal victory? Is it fate itself, stealing the children away? Or are there other, more insidious figures who lure and betray? The ambiguity resonates, suggesting that facile explanations for catastrophic loss are ultimately insufficient, even damaging.

The Sweet Hereafter doesn’t offer catharsis in the traditional sense. There are no easy villains, no neat resolutions. It’s a film that sits with you, heavy and cold, forcing reflection on how communities process trauma, the stories they tell themselves to survive, and the often-unbridgeable gap between public narratives and private truths. It achieved significant critical acclaim upon release, earning Egoyan Oscar nominations for Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay, and winning the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival – remarkable for a Canadian film made with a relatively modest budget (around $5 million CAD).

Rating: 9.5/10

This near-perfect score reflects the film's masterful direction, profound thematic depth, flawless performances (especially from Holm and Polley), and its unforgettable, melancholic atmosphere. It’s a demanding watch, certainly, but its power lies in its refusal to look away from the complexities of grief and truth. It doesn't just depict tragedy; it explores the unsettling quiet that follows, the 'sweet hereafter' that is anything but.

For those of us who encountered this on VHS, perhaps expecting a more straightforward drama, The Sweet Hereafter was a revelation – a film that treated its audience with intelligence and demanded emotional engagement. It remains one of the high watermarks of 90s independent cinema, a haunting meditation on loss that lingers long after the screen goes dark. What story does a community tell itself when the unthinkable happens? This film offers no easy answer, only the chilling, resonant echo of that question.