There’s a particular kind of chill that settles deep in your bones while watching Jim Sheridan's The Field (1990). It’s not just the perpetual dampness of the Irish setting, rendered so vividly you can almost smell the peat smoke and the rain-soaked wool. It's the chilling intensity of obsession, the weight of tradition bearing down like the grey, unforgiving sky, all embodied in one towering, unforgettable performance. Pulling this tape from its worn sleeve often felt like bracing oneself, knowing you were in for something far heavier than your average early 90s rental.

This Land is My Land

Adapted from the acclaimed play by John B. Keane, the premise is deceptively simple: 'Bull' McCabe, a tenant farmer who has painstakingly nurtured a rented field back to fertility over decades, believes it is rightfully his. When the widow who owns the land decides to sell it at public auction, Bull cannot fathom anyone else possessing it, especially not the smooth-talking American (played with suitable unease by Tom Berenger) who arrives intending to pave it over for concrete access. This isn't just about soil and grass; for Bull, this field represents legacy, identity, survival itself. His connection to it feels ancient, almost pagan, a stark contrast to the impending modernity represented by the outsider. Jim Sheridan, fresh off the triumph of My Left Foot (1989), directs with a steady, unflinching hand, letting the raw, elemental power of the story and the landscape dominate.

A Force of Nature Named Harris

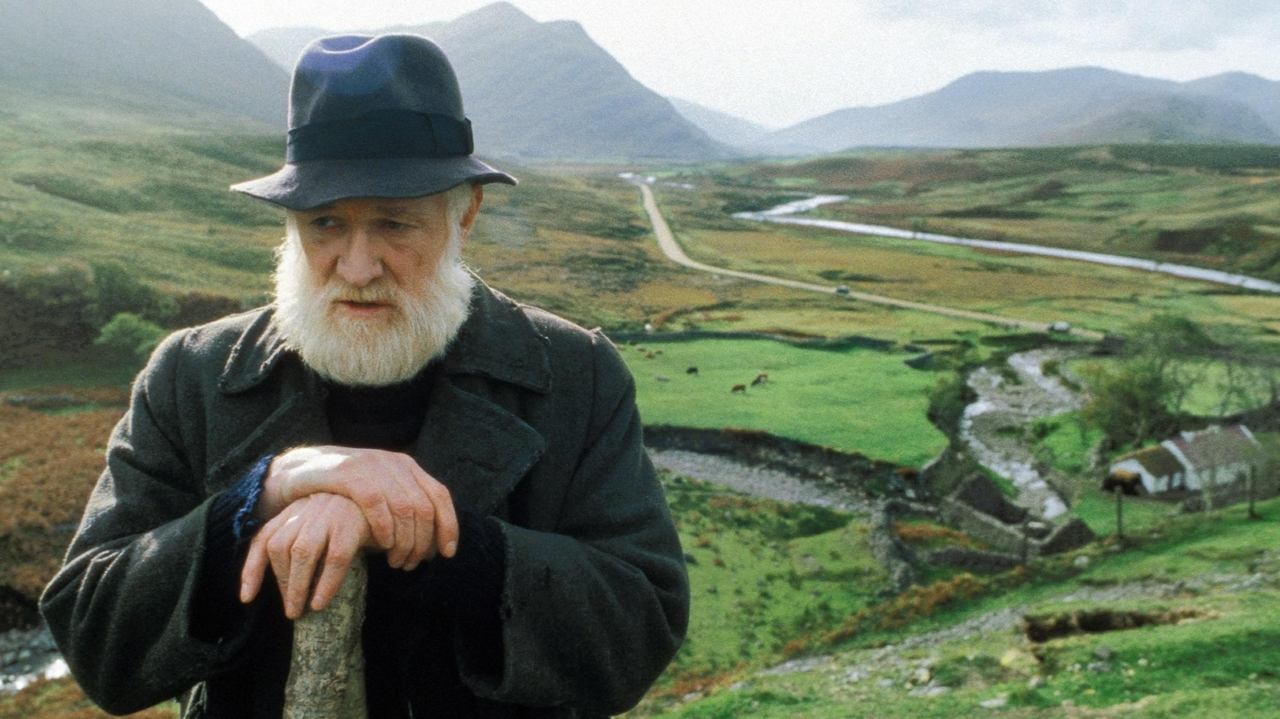

Let's be clear: The Field is utterly dominated by Richard Harris as Bull McCabe. It’s a performance that feels seismic, less acting and more a volcanic eruption of patriarchal pride, simmering rage, and profound, misguided love for the land. Harris, who famously threw himself into roles with fierce commitment, reportedly immersed himself in the local community during filming, absorbing the rhythms and mindset. The result is staggering. His Bull is terrifying, pitiable, and tragically human all at once. Watch his eyes – the fierce glare when challenged, the flicker of vulnerability when contemplating his legacy through his hapless son, Tadgh (a young, earnest Sean Bean). It's a performance etched in stone, a career highlight that rightfully earned Harris his second Oscar nomination. Seeing him here, decades after his musical turn in Camelot (1967) and just before his memorable role in Unforgiven (1992), is to witness an actor operating at the peak of his considerable, often intimidating, power.

Whispers in the Pub, Shadows on the Hill

The supporting cast orbits Bull like wary planets. The great John Hurt, reuniting with Harris decades after they reportedly clashed on the set of Sinful Davey (1969), is perfectly cast as 'The Bird' O'Donnell, Bull's conniving, somewhat slippery confidante. Hurt brings a necessary layer of ambiguity and self-interest to the tight-knit, often suffocating community. Sheridan skillfully uses the pub scenes and furtive conversations to build a palpable sense of communal pressure and shared secrets. You feel the weight of judgment, the fear of crossing Bull, and the quiet complicity that allows tragedy to unfold. Does the community enable Bull, or are they simply powerless against such elemental force? The film leaves you pondering the complex dynamics of such isolated places.

From Stage Roots to Cinematic Scope

Translating a play, especially one so rooted in dialogue and contained intensity, to the screen is always a challenge. Sheridan overcomes this by making the landscape itself a character. Cinematographer Jack Conroy captures the bleak beauty of Connemara – the rolling hills, the stone walls, the ever-present grey sky – making it both visually stunning and deeply oppressive. The harshness of the environment mirrors the harshness within Bull's heart. Filming primarily in and around the village of Leenane, County Galway, lends an undeniable authenticity; this isn't a romanticized Ireland, but a place where survival is scratched from unforgiving earth. One fascinating detail is how the play, written in the 1960s, resonated so strongly again decades later, tapping into enduring themes of land ownership, emigration, and the clash between tradition and progress that were still deeply felt in Ireland as the 90s began.

An Enduring, Unsettling Power

The Field isn't an easy watch. It doesn't offer simple resolutions or comforting moral lessons. It’s a stark portrayal of how obsession can curdle into something monstrous, how deeply rooted beliefs can justify terrible actions. I remember renting this on VHS, perhaps drawn by the Oscar buzz for Harris, and being completely unprepared for its raw, almost brutal honesty. It stood in such stark contrast to the glossier Hollywood fare crowding the shelves back then. There are no heroes here, only flawed human beings caught in a spiral of pride and desperation. What lingers most is the image of Bull McCabe, defiant against the wind and rain, a tragic figure consumed by the very earth he sought to master. It’s a testament to the power of Keane’s original work, Sheridan’s focused direction, and Harris’s unforgettable performance.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the sheer, undeniable power of Richard Harris's central performance, which elevates the film to classic status. Combined with Jim Sheridan's atmospheric direction, the evocative Irish setting, and the enduring relevance of its themes, The Field is a demanding but deeply rewarding piece of cinema. Its bleakness might not be for everyone, but its dramatic intensity is unforgettable.

It leaves you wrestling with unsettling questions about heritage, ownership, and the darkness that can lie beneath the surface of even the most tightly-knit communities. A true heavyweight from the VHS era.