Okay, settle in, grab your beverage of choice, and let's rewind the tape back to 1998. Remember the political landscape then? Slick Willie was in the White House, the economy felt bubbly, but underneath, there was this simmering sense… of something hollow. It’s into that specific cultural moment that Warren Beatty dropped Bulworth, a film less like a polished Hollywood product and more like a cinematic Molotov cocktail hurled directly at the establishment. What happens when a politician, drowning in despair and cynicism, decides the only way out is through unfiltered, brutally honest, hip-hop-infused truth?

Truth Serum via Rhythm and Rhyme

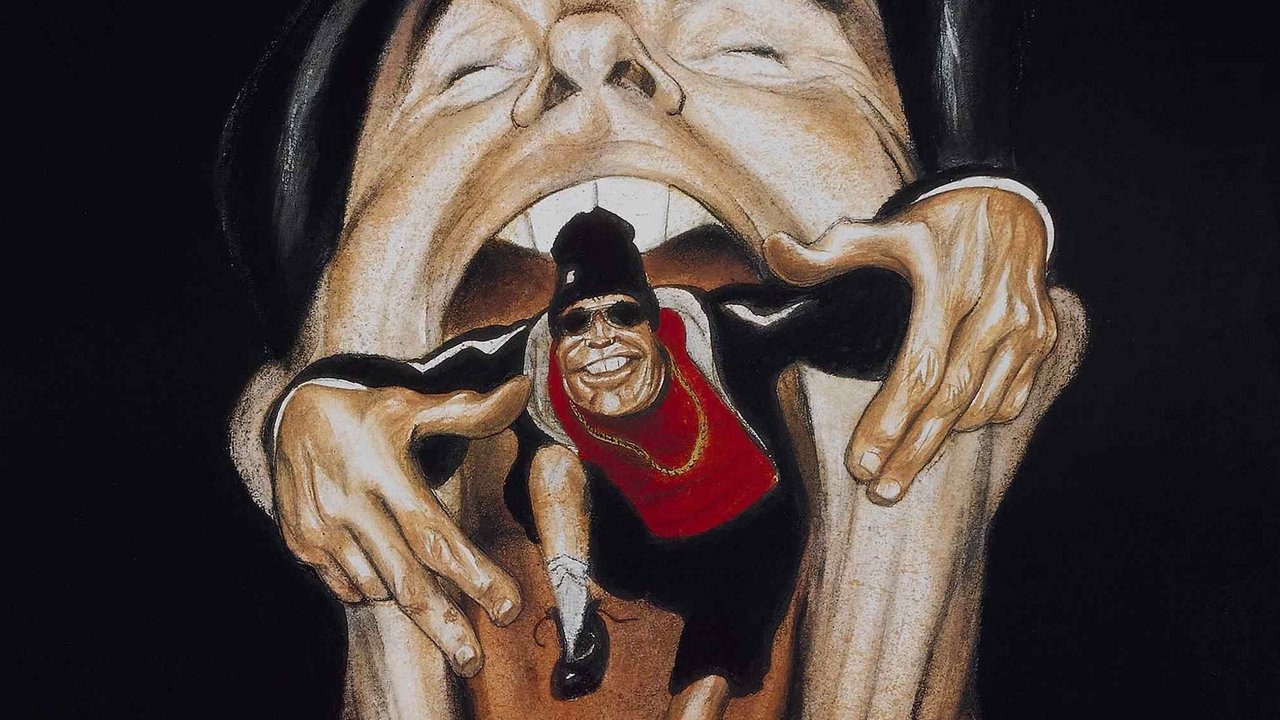

The premise alone feels like a dare. Senator Jay Billington Bulworth (Warren Beatty), a California Democrat facing re-election, is spiritually bankrupt. Trapped in a meaningless marriage, beholden to powerful lobbyists, and utterly disillusioned, he takes out a massive life insurance policy and arranges his own assassination. With seemingly nothing left to lose, he embarks on a final campaign swing, ditching the focus-grouped platitudes for raw, often offensive, rhyming pronouncements about race, corporate greed, and the utter farce of modern American politics. It's a downward spiral that paradoxically becomes an ascent into a strange kind of liberation, fueled by sleepless nights, alcohol, and the vibrant culture of South Central Los Angeles he unexpectedly crashes into.

Beatty, who also directed and co-wrote (with Jeremy Pikser), takes an immense gamble here. Known for his carefully crafted persona both on and off-screen (Reds (1981), Dick Tracy (1990)), seeing him decked out in baggy clothes, adopting hip-hop cadences, and rapping lines like "Yo, everybody gonna get sick someday / But the insurance companies, they want you to pay" is initially jarring, almost surreal. Does it always work? Honestly, sometimes it feels awkward, a patrician figure trying on street cred like an ill-fitting suit. Yet, there's a bizarre conviction Beatty brings to it. The sheer audacity carries much of the performance. You believe Bulworth is genuinely snapping, that this isn't a calculated ploy but a dam bursting. It’s less about technical proficiency in rapping and more about the explosive release of decades of suppressed frustration.

More Than Just a Soundbite

While Beatty’s transformation dominates, the film wouldn't land without its supporting players. Halle Berry, fresh off roles gaining her prominence like in Executive Decision (1996), plays Nina, a politically aware young woman from South Central who becomes Bulworth's guide, conscience, and romantic interest. Berry invests Nina with intelligence and agency, ensuring she’s more than just a catalyst for the Senator’s awakening. She represents the very community Bulworth previously ignored or exploited through empty rhetoric. Their connection feels both unlikely and strangely inevitable, a collision of worlds forced by the Senator's kamikaze mission for truth. And let’s not forget Oliver Platt as Dennis Murphy, Bulworth's increasingly panicked and perpetually exasperated chief of staff. Platt is a master of comedic stress, his reactions providing a necessary anchor (and laughs) amidst the escalating chaos. Look closely too for a sharp early turn from Don Cheadle as L.D., a local drug kingpin whose pragmatic cynicism mirrors Bulworth's own, albeit from a vastly different perspective.

The satire bites hard, targeting Democrats and Republicans alike, the media's obsession with sensationalism over substance, and the insidious influence of big money in politics. Watching it today, some of its critiques feel almost prophetic, don't they? The concerns about healthcare access, insurance industry power, and the disconnect between Washington D.C. and everyday lives resonate with startling clarity. It asks uncomfortable questions about who politics truly serves and what happens when the truth becomes too inconvenient to speak.

Behind the Political Curtain

Getting Bulworth made was reportedly a long-term passion for Beatty. He allegedly spent years developing the script, wanting to tackle the deep-seated issues he saw plaguing the American political system. It was a risky proposition for a major studio – a dark, R-rated political satire with a rapping protagonist wasn't exactly a guaranteed blockbuster formula. Indeed, on a budget of around $30 million, it barely recouped its costs at the box office, grossing just over $29 million worldwide. Its initial reception was mixed, with some critics hailing its boldness and others finding it preachy or clumsy.

One fascinating production choice was bringing in legendary composer Ennio Morricone, famed for his iconic Western scores (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)), to score this very contemporary, hip-hop-infused satire. It's an unexpected pairing that somehow adds another layer to the film's slightly surreal, off-kilter feel. Beatty also insisted on shooting significant portions on location in South Central L.A., adding a layer of authenticity to Bulworth's journey. And yes, Beatty performed all his own rapping – reportedly receiving coaching to get the rhythm and flow down, a commitment that adds to the strange sincerity of the performance, even in its awkward moments. It wasn't just a gimmick; it was central to the character's radical transformation.

The Lingering Echo

Bulworth isn't a perfect film. Its tone can occasionally wobble, the romantic subplot sometimes feels a bit forced, and the abrupt ending leaves viewers deliberately unsettled, a choice that still sparks debate. Yet, its imperfections are part of its ragged charm, its raw energy. It doesn't offer easy answers; instead, it throws a grenade into the room and forces you to grapple with the shrapnel. It’s a film that feels uniquely of its moment – that late 90s blend of cynicism and lingering idealism – yet its core message about political honesty (or the lack thereof) feels startlingly relevant. Did you catch this one back in the day? I remember renting the tape, perhaps from Blockbuster or maybe a smaller local spot, drawn in by the bizarre premise and Beatty's name, and being utterly unprepared for the strange, provocative journey it offered. It wasn't comfortable viewing then, and it isn't now, but its willingness to provoke thought sticks with you.

Rating: 7/10

This score reflects the film's undeniable audacity, its sharp (if sometimes blunt) satire, and Beatty's go-for-broke performance. It loses points for occasional tonal unevenness and narrative elements that don't fully coalesce. However, its willingness to tackle thorny issues head-on, its snapshot of late 90s anxieties, and its sheer unforgettable strangeness make it a compelling, if flawed, piece of political cinema from the VHS era.

It leaves you wondering: in an age saturated with carefully managed political messaging, could a Bulworth even exist today, and perhaps more importantly, would anyone listen?