There's a profound quietness that settles around Ian McKellen's portrayal of James Whale in Gods and Monsters (1998), a stillness that belies the storms raging within. It’s not the bombast of his famous horror creations, but the fragile twilight of a life lived large, now grappling with decline, memory, and the ghosts of his own making. Watching it again, decades removed from its initial release – perhaps discovered on a late-run VHS or an early DVD find – the film resonates with an adult melancholy, a poignant exploration of artistry, desire, and the complex dance between creator and creation.

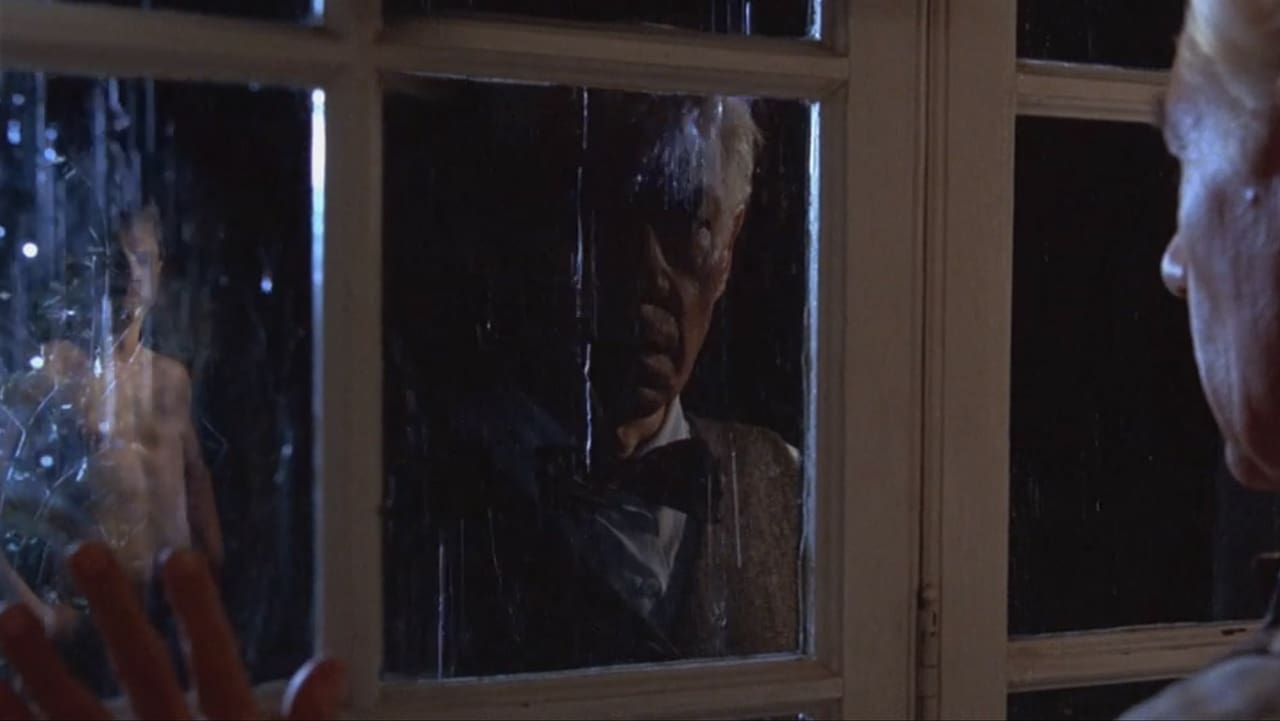

Set primarily in 1957, the film imagines the final days of James Whale, the British director celebrated for classics like Frankenstein (1931) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935), now living in semi-retirement in sun-drenched California. Following a stroke, his health failing and his mind increasingly adrift in vivid, sometimes harrowing, recollections of his past – from the trenches of World War I to the glittering, often hypocritical, heights of Hollywood – Whale finds himself intrigued by his new, strapping young gardener, Clayton Boone (Brendan Fraser). What begins as a seemingly simple request for Boone to pose for sketches evolves into a complex, manipulative, yet strangely tender relationship that forces both men to confront uncomfortable truths about themselves.

An Unlikely Pas de Deux

The absolute core of Gods and Monsters lies in the interactions between McKellen's Whale and Fraser's Boone. McKellen is simply extraordinary. He doesn't just impersonate Whale; he inhabits his weariness, his lingering wit, his piercing intelligence, and the profound loneliness beneath the sophisticated, sometimes predatory, facade. It’s a performance built on subtle shifts in expression, the flicker of memory in his eyes, the slight tremor in his hand – a masterclass in conveying a universe of experience without resorting to grandstanding. It’s easy to see why this performance garnered him an Academy Award nomination; it feels less like acting and more like witnessing a soul laid bare.

Equally crucial, though perhaps less initially lauded, is Brendan Fraser as Clayton Boone. This was a role that came when Fraser was arguably better known for lighter fare like George of the Jungle (1997) or the cusp of The Mummy (1999). Seeing him here, playing this seemingly simple, heterosexual ex-Marine, grappling with the complex attentions of an aging, gay intellectual, was a revelation. Fraser brings a crucial authenticity to Boone – a mix of politeness, confusion, discomfort, and a burgeoning, reluctant empathy. He’s not merely an object of Whale’s gaze; he’s a man with his own past, his own insecurities, and his own dawning understanding of lives lived differently. The tentative trust and boundaries negotiated between them feel incredibly real, making their dynamic the film's powerful engine. Their scenes together crackle with unspoken tensions and surprising moments of connection.

Beyond the Garden Gate

Director Bill Condon, who also adapted the screenplay from Christopher Bram's novel Father of Frankenstein (and won an Oscar for his efforts), crafts the film with remarkable sensitivity and intelligence. He deftly balances the present-day interactions with Whale's fragmented memories, using black-and-white sequences that evoke both the horror director's cinematic past and the stark trauma of war. These flashbacks aren't just exposition; they inform Whale's present state, explaining the origins of his fascination with monsters, both literal and metaphorical. Condon avoids sensationalism, treating Whale's homosexuality and desires with matter-of-fact honesty, a significant achievement for a mainstream-accessible film in the late 90s.

Adding another layer of brilliance is Lynn Redgrave as Hanna, Whale's fiercely protective, long-suffering Hungarian housekeeper. Redgrave, also Oscar-nominated for her role, provides not just comic relief (though her sharp observations are often wryly funny) but the film's moral compass. Her relationship with Whale is a complex tapestry of exasperation, loyalty, and deep, unspoken affection. She sees through his games, understands his pain, and fiercely guards his dignity, even when disapproving of his actions. Her presence grounds the film, offering an essential counterpoint to the central, charged relationship. It's worth noting this film was a passion project for Condon, made on a relatively modest budget of around $3.5 million, proving that powerful human stories don't require blockbuster resources.

The Monster Within and Without

Ultimately, Gods and Monsters is a meditation on legacy, loneliness, and the search for understanding in the face of mortality. Whale, the creator of one of cinema's most enduring monsters, finds himself confronting the "monsters" of his own past and present – illness, prejudice, lost love, the fading of his creative fire. Boone, initially perceived perhaps as a kind of handsome, simple "creature" by Whale, reveals his own humanity and capacity for unexpected connection. Doesn't this exploration of aging and the confrontation with one's past resonate deeply, regardless of the specifics of Whale's life? The film asks us to consider who the real "monsters" are – are they the grotesque figures on screen, or the societal prejudices and personal demons we all carry?

It’s a film that lingers, not because of shocking twists or grand pronouncements, but because of its quiet observations, its emotional honesty, and the sheer power of its central performances. It feels like a treasure unearthed, perhaps from the back shelf of the video store, a reminder of the kind of thoughtful, character-driven drama that sometimes felt rare even then.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's exceptional performances, particularly from McKellen and Fraser, its intelligent and sensitive script, Condon's masterful direction, and its profound exploration of complex themes. It's a near-perfect character study that treats its subject with nuance and deep humanity, avoiding easy answers or judgments. The slight deduction might only be for pacing that demands patient viewing, fully rewarding those who invest.

Gods and Monsters remains a potent and moving piece of cinema, a haunting look at the twilight of a creative life and the unexpected connections that can illuminate the encroaching darkness. It reminds us that sometimes, the most compelling stories are not about heroes and villains, but about the messy, complicated, and deeply human spaces in between.