The rain that falls in Ken Loach’s Britain isn’t just water; sometimes, it feels like hardship itself, an endless downpour of misfortune soaking the spirits of those just trying to get by. Watching Raining Stones (1993) again after all these years, pulling it from the metaphorical shelf of memory much like we once pulled tapes from Blockbuster, is to be struck anew by its raw, unvarnished humanity. It’s a film that settles deep in your bones, less concerned with spectacle and more with the quiet, crushing weight of circumstance, and the fierce, sometimes flawed, dignity people cling to when facing it.

A Father's Promise in Trying Times

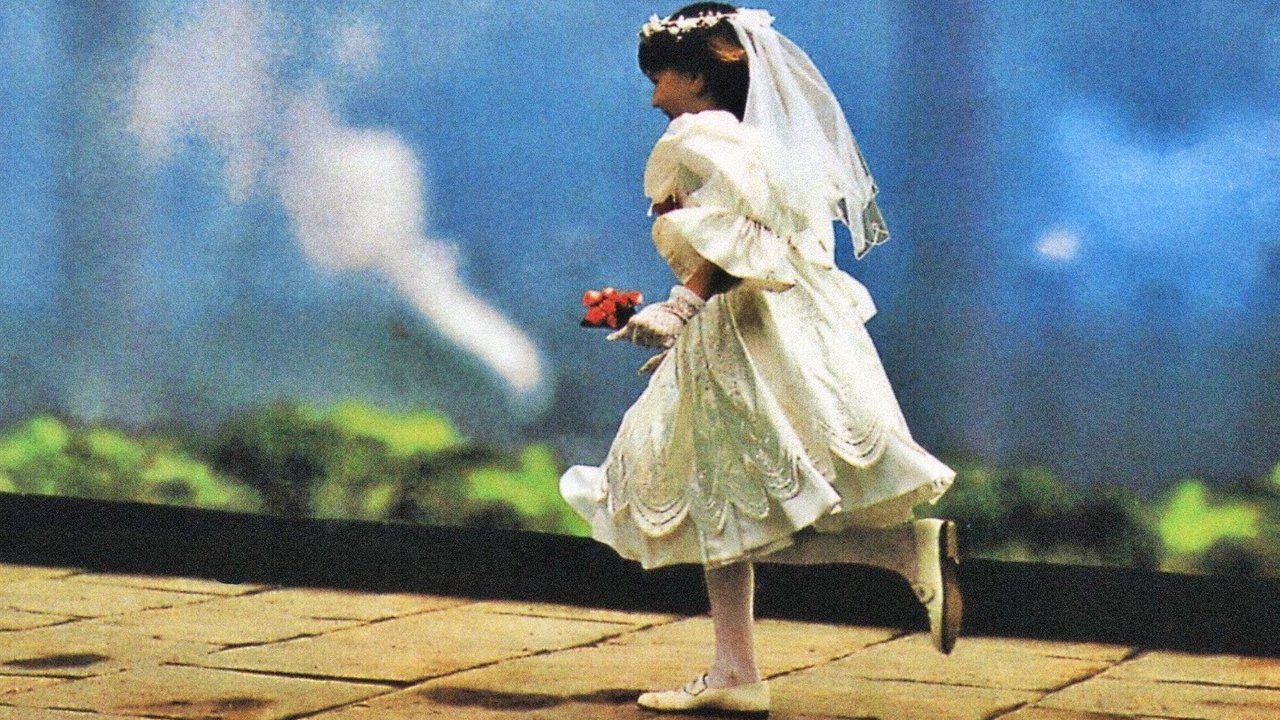

Set against the backdrop of early 90s Greater Manchester, a landscape etched with the scars of unemployment and economic neglect (a reality many watching on their CRTs back then would have recognised all too well), we meet Bob Williams, played with heart-wrenching authenticity by Bruce Jones. Bob is jobless, skint, but fiercely proud and devoted to his family. His immediate goal seems simple, almost mundane: find the money for his young daughter Coleen’s First Communion dress. Yet, in this world meticulously crafted by Loach and his long-time collaborator, writer Jim Allen (whose ear for authentic working-class dialogue was unparalleled), this small symbol of faith and tradition becomes an Everest Bob must climb, revealing the precariousness of life on the margins. His loving wife Anne (Julie Brown, equally grounded and moving) offers quiet support, while his mate Tommy (Ricky Tomlinson, radiating weary warmth long before becoming Jim Royle) provides camaraderie, but the burden ultimately falls on Bob.

The Loach Touch: Grit and Grace

If you were expecting polished Hollywood melodrama, you’d have ejected the tape pretty quickly. Ken Loach, already a master of social realism with films like Kes (1969) under his belt, directs with an unflinching gaze. There’s no artificial lighting softening the edges here, no soaring score manipulating emotions (though Stewart Copeland of The Police provided a subtle, effective one). Instead, Loach uses naturalistic cinematography and often lengthy takes, immersing us completely in Bob’s world. It’s a testament to his method – often keeping actors slightly in the dark about upcoming scenes to elicit genuine reactions – that the performances feel less like acting and more like bearing witness. You can almost feel the damp chill in the air, the texture of the worn furniture, the palpable anxiety simmering beneath the surface. It’s said that Loach and Allen aimed to capture the resilience and humour alongside the hardship, and that delicate balance is achieved brilliantly here.

When Pride Pushes Too Hard

At its core, Raining Stones is a profound study of pride and desperation. Bob’s inability to accept charity, even from the sympathetic local priest, Father Barry (Tom Hickey), is both frustrating and deeply understandable. It’s this pride that fuels his increasingly risky schemes – pinching a sheep from the moors (a sequence laced with grimly funny incompetence), doing odd jobs, and eventually, fatefully, borrowing money from a predatory loan shark. Bruce Jones embodies Bob’s struggle entirely. Before his long tenure on Coronation Street, Jones delivered a performance here that feels ripped from reality – the forced cheerfulness masking deep worry, the flashes of anger born of impotence, the overwhelming love for his daughter that drives him to the brink. How far would any of us go to preserve our family’s dignity, or even just to fulfill a simple promise to a child? The film doesn’t offer easy answers.

Finding Light in the Cracks

Despite the pervasive sense of struggle, Raining Stones isn't relentlessly bleak. There are moments of genuine warmth and community spirit, particularly in the scenes shared between Bob and Tommy. Their banter, their shared pints, their slightly disastrous attempts at navigating life’s obstacles provide not just comic relief, but a crucial sense of solidarity. These flashes of humour, often dark and ironic, make the subsequent turns of the screw feel even sharper. The film understands that laughter and tears often live side-by-side in communities under pressure. A fascinating production note: the film was made for around £900,000 – a modest sum even then – yet it resonated powerfully enough to win the prestigious Jury Prize at the 1993 Cannes Film Festival, proving that potent storytelling doesn't always need blockbuster budgets.

The Unflinching Climax and Lingering Questions

Spoiler Alert! The narrative tightens unbearably as Bob falls deeper into debt with the loan shark. The confrontation that follows is shocking, desperate, and morally complex. When Father Barry becomes involved in the aftermath, his counsel and actions challenge conventional notions of sin, forgiveness, and justice within the Catholic faith and the wider community. What constitutes the greater sin – Bob's desperate act, or the systemic neglect that pushed him there? The film refuses simple judgments, leaving the viewer to grapple with the uncomfortable ambiguities. It’s a conclusion that stays with you, forcing a reflection on the impossible choices poverty can impose.

Why It Endures on the Shelf of Memory

Raining Stones might not have been the Friday night popcorn flick you rented for pure escapism back in the day. It was, and remains, something more vital: a profoundly moving, sometimes uncomfortable, but ultimately compassionate portrait of working-class resilience. It captured a specific moment in British social history with an honesty that few films achieve. Seeing Bruce Jones and Ricky Tomlinson in these raw, powerful roles before their later television fame is a potent reminder of their range. For those of us browsing the aisles of "VHS Heaven," rediscovering Raining Stones is like finding a hidden gem – perhaps not gleaming, but possessing a deep, enduring lustre. It’s a reminder that amidst the action heroes and sci-fi epics of the era, cinema also offered powerful reflections of the world just outside the video store window.

Rating: 9/10

This rating reflects the film's masterful execution of its social realist aims, the powerhouse authenticity of its performances (especially Bruce Jones), and its unflinching yet compassionate exploration of complex themes. It achieves precisely what it sets out to do with startling clarity and emotional depth, making it a standout work in Ken Loach's significant filmography.

Raining Stones leaves you contemplating the invisible burdens people carry, and the quiet strength it takes just to keep putting one foot in front of the other when life feels like an unrelenting storm. A vital piece of British cinema that feels as relevant now as it did back in '93.