You press play, the tracking adjusts, and the familiar whirring sound settles. But what unfolds isn't comfort. It's a cinematic assault. Some films ease you in; Takashi Miike’s 1999 crime opera Dead or Alive (デッド・オア・アライブ 犯罪者 - Deddo oa Araibu: Hanzaisha) grabs you by the throat in its opening minutes and dares you to look away. Forget subtle foreshadowing – this is a declaration of war, a six-minute montage of hyper-stylized depravity, violence, and excess set to a driving beat that feels less like an introduction and more like a mainlined shot of pure cinematic adrenaline. It’s the kind of opening that likely had rental store clerks fielding bewildered calls back in the day.

Shinjuku Noir Nightmares

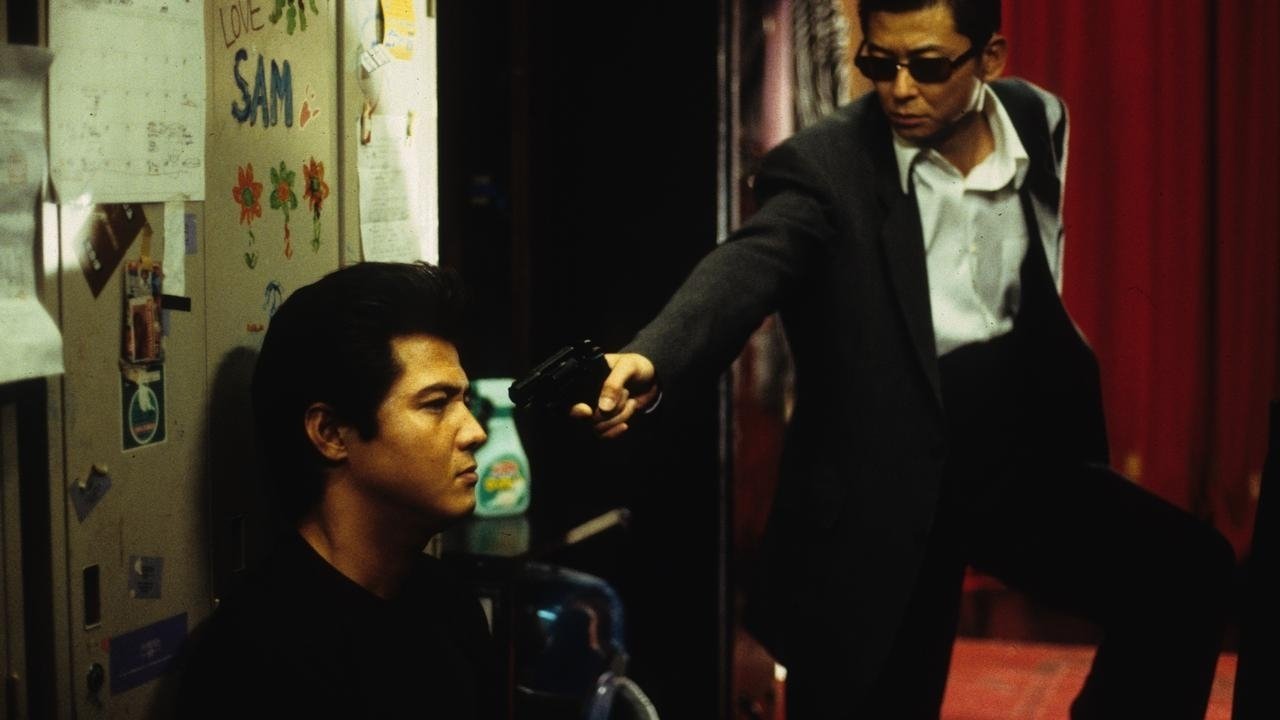

Set against the grimy, neon-drenched backdrop of Tokyo’s Shinjuku district, the plot, on the surface, is deceptively simple: Detective Jojima (Show Aikawa, a V-Cinema legend often paired with Miike) is a world-weary cop obsessed with bringing down Ryuichi (Riki Takeuchi, another stalwart of Japanese direct-to-video action, known for his imposing presence), an ambitious Triad gangster carving out his territory with ruthless efficiency. It's a classic cops-and-robbers setup, but filtered through Miike's uniquely anarchic lens, it becomes something far stranger, more brutal, and ultimately, more nihilistic.

The atmosphere isn't just dark; it's oppressive. Miike, working with writer Ichiro Ryu, drenches the screen in shadows, claustrophobic interiors, and sudden bursts of shocking violence. Remember the feeling of watching something truly transgressive on a worn VHS tape, something that felt illicit and dangerous? Dead or Alive bottles that sensation. The handheld camerawork often feels frantic, mirroring the characters' desperation, while the score lurches between moody ambiance and jarring electronic pulses. It’s a film that feels dangerous to watch, even now.

Two Sides of the Same Corroded Coin

The dynamic between Aikawa’s Jojima and Takeuchi’s Ryuichi is the film's black heart. They aren’t just cop and criminal; they’re mirrors reflecting different facets of societal breakdown and masculine rage. Aikawa plays Jojima with a quiet desperation, a man burdened by debt, a sick daughter, and the crushing weight of the city's corruption. Takeuchi, conversely, embodies pure, volatile ambition. His Ryuichi is charismatic but utterly savage, a force of nature tearing through the underworld. Their inevitable collision course feels less like a pursuit of justice and more like a doomed, fatalistic dance. There’s a raw energy to their confrontations, fueled by the actors' established screen personas and palpable chemistry – they’d already faced off numerous times in the V-Cinema world, and Miike weaponizes that history here.

Miike himself was famously prolific during this period, sometimes directing half a dozen films a year, often on tight budgets and tighter schedules. This relentless pace arguably fueled the raw, unpolished energy of films like Dead or Alive. Legend has it that the infamous, explosive opening montage was conceived relatively late in production, partly as a way to grab the audience immediately and make a virtue of the chaotic energy inherent in its V-Cinema roots. It reportedly cost a significant chunk of the film's modest budget but undeniably set the tone. You can almost feel the guerrilla filmmaking spirit – shooting quickly, pushing boundaries, aiming for maximum impact with minimal resources.

Beyond the Bloodshed

While the film is notorious for its violence – and make no mistake, it is often graphic and unsettling, including that noodle shop scene – it’s not just empty shock value. Miike uses the extremity to explore themes of displacement (Ryuichi and his gang are ethnic Chinese immigrants, outsiders in Japan), the corrupting influence of power, family loyalty (however twisted), and the ultimate pointlessness of the violent cycle. It’s messy, provocative, and refuses easy answers. Doesn't the sheer nihilism of its worldview still feel potent, even unsettling, today?

And then there’s the ending. (Minor spoilers ahead, but avoiding specifics) Without giving away the precise details, the final moments of Dead or Alive are so audacious, so completely out-of-left-field, that they’ve become legendary. It’s a conclusion that defies logic, genre conventions, and possibly physics itself. It’s the kind of ending that leaves you stunned, confused, maybe even laughing in disbelief, but you certainly won't forget it. Was it a budget-saving measure? A final, defiant middle finger to convention? Whatever the reason, it seals the film's cult status. It’s pure, uncut Miike.

Lasting Impact

Dead or Alive wasn't just another V-Cinema flick; its sheer audacity and stylistic flair helped solidify Takashi Miike's international reputation as a fearless provocateur. It spawned two thematic sequels, Dead or Alive 2: Birds (2000) and Dead or Alive: Final (2002), each distinct in tone and style but connected by the core actors and Miike's unpredictable vision. While perhaps lacking the polish of some of his later works like Audition (released the same year, incredibly) or 13 Assassins (2010), Dead or Alive possesses a raw, untamed energy that perfectly encapsulates the wild west of late 90s Japanese genre filmmaking. It’s a film that feels like it was smuggled into existence, a burst of chaotic brilliance from the VHS underground.

***

Rating: 8/10

Justification: Dead or Alive earns its high score through sheer, unadulterated audacity and Miike's singular vision. The iconic opening, the potent dynamic between Takeuchi and Aikawa, the relentlessly grim atmosphere, and the mind-bending ending make it unforgettable. While its narrative can feel disjointed and the extreme content isn't for everyone, its raw energy and influential style are undeniable. It’s a cornerstone of Miike’s prolific output and a defining example of late 90s Japanese cult cinema.

Final Thought: This isn't just a movie; it's an experience – abrasive, shocking, and darkly brilliant. It’s a perfect time capsule of a director hitting his stride and refusing to play by anyone's rules, a Molotov cocktail thrown directly at the screen, leaving scorch marks on your VCR heads and your psyche.