Some films detonate expectations. You press play, braced for one kind of cinematic explosion, only to find yourself caught in the fallout of something altogether different, something quieter, stranger, and maybe even more resonant. Stepping into Takashi Miike’s Dead or Alive 2: Birds (2000) after its utterly berserk predecessor feels exactly like that. Forget the city-leveling chaos; this time, Miike trades relentless nihilism for a bruised, almost poetic melancholy, wrapped around bursts of hyper-stylized violence that still hit like a shotgun blast to the chest.

A Different Kind of Hit

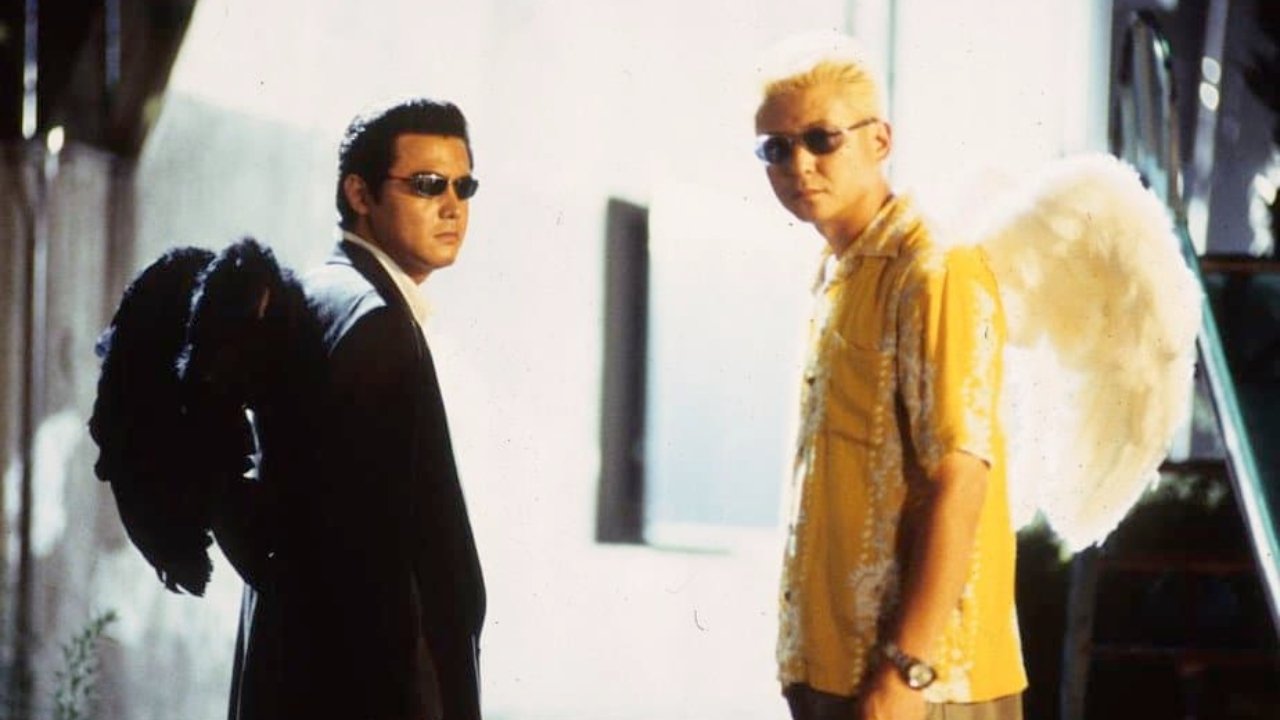

Where the original Dead or Alive (1999) was a fever dream of yakuza absurdity culminating in... well, that ending, DOA 2 takes a sharp, unexpected turn. We reunite with V-Cinema titans Riki Takeuchi and Show Aikawa, but not as the characters from the first film. Here, they play Mizuki and Shuuichi, rival assassins who discover they grew up together in the same island orphanage. Their chance reunion triggers a pact: complete one last high-stakes job together, use the money to revisit their childhood home, and maybe, just maybe, find some peace. It’s a setup that feels almost wistful, a stark contrast to the director often labeled Japan's enfant terrible of extreme cinema. Miike, known for his prolific output (sometimes juggling multiple films simultaneously, a pace almost unthinkable outside the demanding Japanese V-Cinema system), seemed determined here to explore the soul behind the trigger finger.

Childhood Ghosts and Bullet Casings

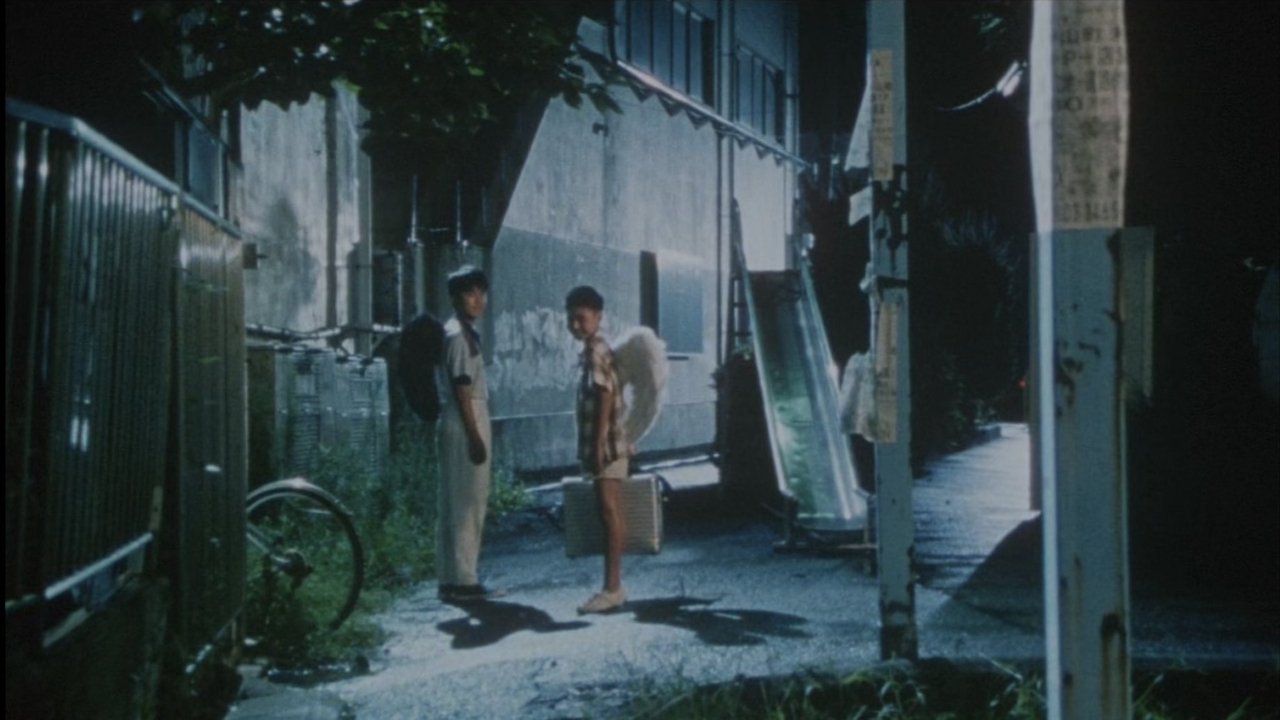

The heart of DOA 2 lies in this unexpected thematic detour. Mizuki and Shuuichi’s journey back to the orphanage isn’t just a plot device; it's the film's soul. They interact with the children currently living there, helping them stage a school play, awkwardly attempting to recapture fragments of their own lost innocence. These scenes, juxtaposed with the brutal realities of their profession, create a jarring but fascinating dissonance. Miike lingers on moments of quiet connection – sharing a meal, watching children play – giving them as much weight as the meticulously choreographed gunfights. This tonal balancing act is classic Miike, pushing boundaries not just with violence, but with emotional whiplash. Did you find this shift as surprising as I did back then, expecting wall-to-wall mayhem?

The action, when it comes, is pure Miike, albeit filtered through this new lens. It’s stylized, balletic, and utterly lethal. One standout sequence involving an angelic assassin descending on wires is both ludicrous and breathtaking – a perfect example of Miike’s unique aesthetic. These bursts of violence feel less like the point of the film and more like the inescapable gravity of the protagonists' lives, pulling them back from the fragile hope they find on the island. It’s rumored that Takashi Miike deliberately chose Sado Island for its remote, isolated feel, amplifying the sense that this orphanage is a world away from the characters' blood-soaked reality, a sanctuary perpetually under threat.

V-Cinema Royalty

You can't talk about DOA 2 without praising its leads. Riki Takeuchi (Mizuki), with his imposing presence and signature scowl, brings a simmering intensity, hinting at the pain beneath the hardened exterior. Show Aikawa (Shuuichi), often the smoother operator in their many V-Cinema pairings, delivers a performance tinged with weariness and a desperate yearning for normalcy. Their established chemistry, honed over countless direct-to-video yakuza flicks that were staples of Japanese rental stores, gives their reunion an immediate, lived-in feel. They embody the tragic paradox of the film: killers dreaming of playground swings. Noriko Aota also offers a grounding presence as Shuuichi's partner, caught in the crossfire of his past and present.

Feathers and Finality

The "Birds" subtitle isn't just window dressing. Avian imagery flutters throughout the film, most notably in the recurring motif of white doves – symbols of peace tragically intertwined with acts of violence. It culminates in an ending that is pure, uncut Miike: operatic, bloody, strangely beautiful, and deeply melancholic. It doesn't offer easy answers, instead leaving you with a haunting tableau that sticks long after the credits roll (or the tape clicks off). It’s a far cry from the explosive absurdity of the first film's finale, opting for something more akin to a blood-soaked poem. This thematic trilogy – DOA, DOA 2: Birds, and Dead or Alive: Final (2002) – feels less like a traditional series and more like Miike using the same actors and title concept to explore wildly different facets of violence, loyalty, and existence.

The Verdict

Dead or Alive 2: Birds isn't the film you might expect based on its title or its director's reputation for shock value. It's a surprisingly affecting, often beautiful meditation on lost innocence and the inescapable cycle of violence, punctuated by bursts of masterful action choreography. While its tonal shifts might be jarring for some, and the Miike-brand violence is definitely not for the squeamish, the film's ambition and emotional depth are undeniable. It showcases Takashi Miike’s versatility beyond pure extremity, proving he could blend bullets with a surprising amount of heart. It might lack the sheer cult insanity of the original, but it offers something arguably more lasting. Finding this gem back in the day, perhaps nestled between more straightforward action flicks on the rental shelf, felt like discovering a secret handshake into a wilder, more thoughtful corner of genre cinema.

Rating: 8/10

This film stands as a fascinating anomaly in Miike's vast filmography and a high point of the Dead or Alive trilogy. It’s a violent poem that dares to dream, even as the blood pools at its feet, making it a truly unique artifact from the turn of the millennium's cinematic landscape.