Here we go, sliding another tape into the VCR of memory. This time, it’s a film that arrived just as the millennium was turning, a picture carrying the weight of a legendary director and a star known more for martinis than moccasins. Richard Attenborough’s Grey Owl (1999) presents a story almost too strange to be true, forcing us to confront the tangled roots of identity, fame, and the stories we tell ourselves – and the world. It wasn't the kind of explosive blockbuster lighting up the multiplexes as the 90s closed, but rather a thoughtful, beautifully crafted piece that perhaps felt a little out of step, demanding a quieter contemplation many weren't looking for amidst the Y2K buzz.

A Wilderness of Mirrors

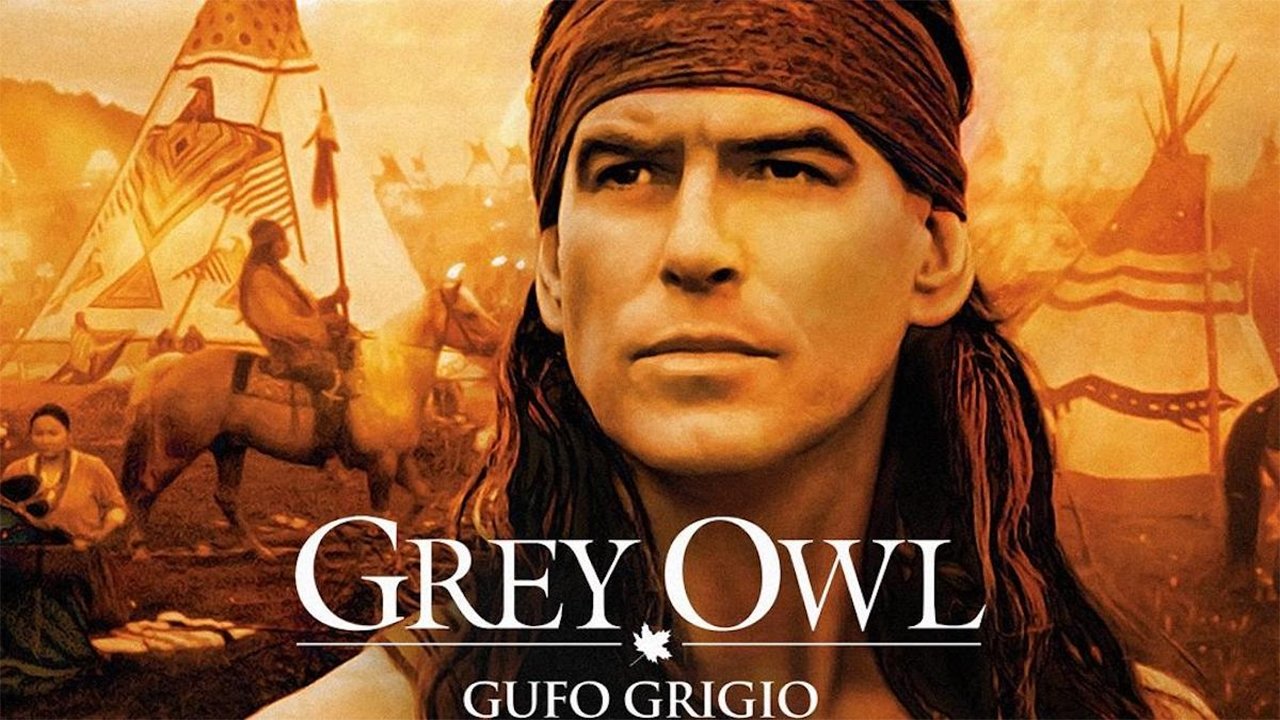

What immediately draws you into Grey Owl isn't just the stunning Canadian wilderness, captured with the expected reverence by Attenborough (who gave us the sweeping vistas of Gandhi and the intimate sorrows of Shadowlands), but the central figure himself. Pierce Brosnan, then at the peak of his James Bond fame, takes on the role of Archibald Belaney, an Englishman who, in the early 20th century, completely reinvented himself as Grey Owl, a Native American trapper turned passionate conservationist. The film introduces him as this idealized figure, living in harmony with nature, writing books that captivated the world, lecturing kings. But beneath the stoic facade and adopted heritage lies a profound deception, one the film slowly peels back. Isn't it fascinating how someone can construct an entire persona, live it so fully, yet base it on a fundamental untruth?

Brosnan's Burden

The weight of the film rests heavily on Brosnan's shoulders. It's a challenging role – portraying not just Grey Owl, the revered naturalist, but also Archie Belaney, the man underneath, wrestling with his fabricated identity. It’s a performance marked by a quiet intensity. You see flashes of the hidden Englishman – a turn of phrase, a flicker of discomfort – beneath the weathered exterior. Released between Tomorrow Never Dies (1997) and The World Is Not Enough (1999), seeing Bond trade his Walther PPK for a canoe paddle was certainly a shift. While some critics at the time felt Brosnan didn't fully disappear into the role, I find his performance holds a certain poignancy. He conveys the burden of the lie, the yearning for authenticity even within the artifice. He's playing a man playing a part, and there's an inherent sadness in that which Brosnan captures effectively. Does the knowledge of his Bond persona perhaps make the transformation more intriguing for us viewers now, highlighting the very nature of assumed identities?

Anahareo's Truth

Crucial to the narrative is Anahareo, nicknamed Pony, portrayed with wonderful spirit and grounding authenticity by Annie Galipeau. A young Iroquois woman, she becomes Grey Owl's partner and muse, and it's largely through her influence that he transitions from trapping to conservation. Galipeau is the film's heart; her perspective provides the emotional anchor and, importantly, a genuine Indigenous voice within the story. Her journey – from initial admiration to disillusionment and eventual understanding – mirrors the audience's own complex reaction to Grey Owl's story. The chemistry between Brosnan and Galipeau feels gentle and believable, forming the core relationship that drives the narrative forward.

Attenborough's Passion, Nicholson's Words

You can feel Lord Attenborough's deep personal connection to this project; he reportedly spent decades trying to bring Belaney's story to the screen. His direction is classical, patient, allowing the stunning landscapes (filmed beautifully in locations like Quebec's Harrington Lake and Prince Albert National Park in Saskatchewan) to breathe, becoming almost a character in themselves. There's a palpable love for the natural world here, echoing Grey Owl's own (adopted) message. The screenplay, by William Nicholson (who also penned Gladiator and Attenborough’s Shadowlands), delicately handles the complexities of Belaney's life, avoiding easy judgments. It asks us to consider the impact of Grey Owl's conservation work, even while acknowledging the problematic foundation of his identity. Could his vital message have been heard without the constructed persona? It’s a question the film leaves us pondering.

Retro Fun Facts & Lingering Thoughts

It’s interesting to remember the context: the real Grey Owl became an international sensation in the 1930s. His lectures, including one for King George VI, were major events. The revelation after his death in 1938 that he was actually English caused a massive scandal, tarnishing his legacy for decades. Attenborough's film aimed, in part, to re-examine that legacy, focusing on the sincerity of his environmental passion despite the deception. The film itself, budgeted around $30 million, sadly didn't make a huge splash at the box office, perhaps proving too quiet or complex for mainstream tastes at the time. I recall seeing the VHS box on the rental store shelf, sandwiched between louder fare, its thoughtful cover promising something different. It felt like a film made for adults, a throwback even then to character-driven dramas.

The film isn't without flaws. The pacing can feel somewhat stately, adhering perhaps too closely to biopic conventions at times. And the central question of cultural appropriation hangs heavy – can we separate the positive impact of Grey Owl's conservation advocacy from the troubling fact that he built his platform by assuming an identity that wasn't his? The film presents the facts, the relationships, the beauty, but leaves the final moral judgment largely to the viewer.

Rating: 7/10

Grey Owl earns a solid 7. While occasionally conventional in its storytelling, it's elevated by Attenborough's assured direction, the breathtaking cinematography, Galipeau's soulful performance, and Brosnan's committed portrayal of a deeply conflicted man. Its willingness to engage with complex themes of identity, cultural borrowing, and the enduring power of the natural world gives it a depth that lingers. It doesn't offer easy answers, reflecting the messy reality of its subject's life.

It remains a fascinating, beautifully rendered slice of history, a reminder from the cusp of the 21st century about a peculiar early 20th-century enigma. It’s the kind of film that sparks conversation, leaving you turning over the central paradox long after the tape has clicked off: can a lie ultimately serve a greater truth?