The rain never seems to stop. It hammers against the corrugated iron, drips incessantly through cracked ceilings, pools in the grimy stairwells of a Taipei apartment block teetering on the edge of the new millennium. This oppressive, aqueous soundscape is the first thing that truly settles over you when watching Tsai Ming-liang's 1999 film The Hole (Dong), a viewing experience that feels less like watching a movie and more like being submerged in a very specific, unsettling mood. It’s the kind of film that likely bypassed the main aisles of Blockbuster, maybe tucked away in a dusty corner of the "World Cinema" section, waiting for the curious or the adventurous.

Millennial Dread, Amplified

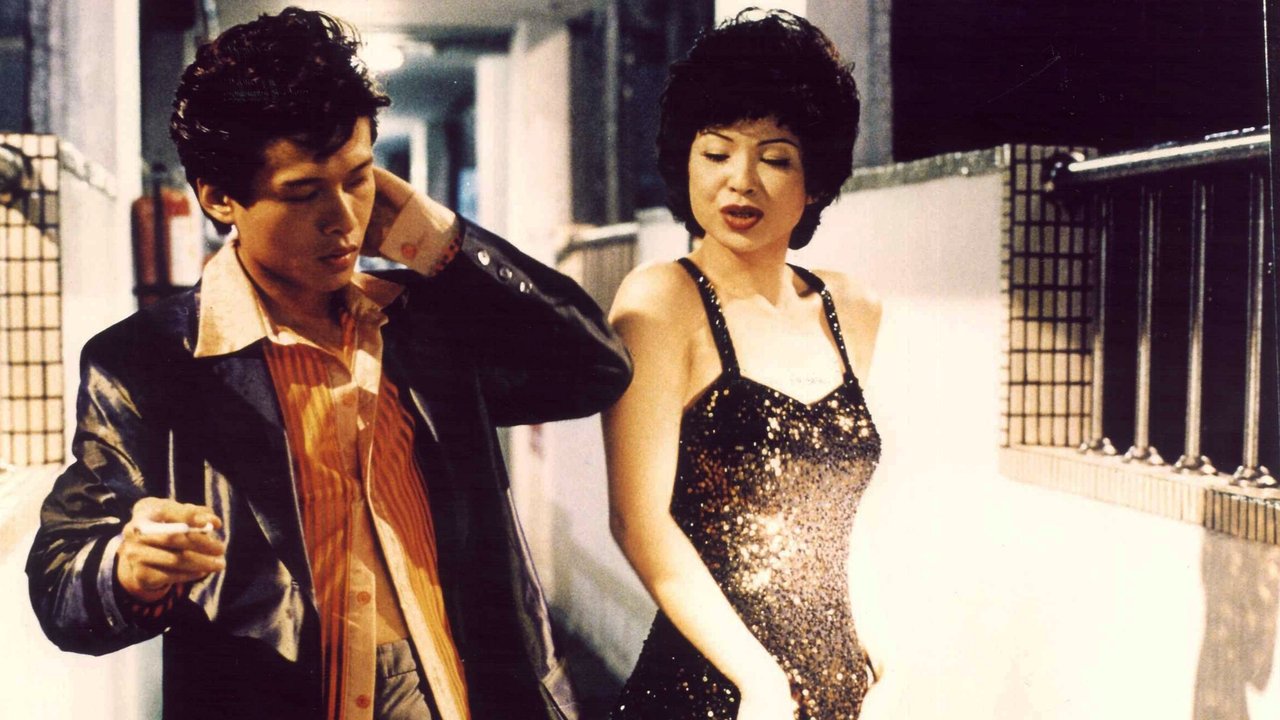

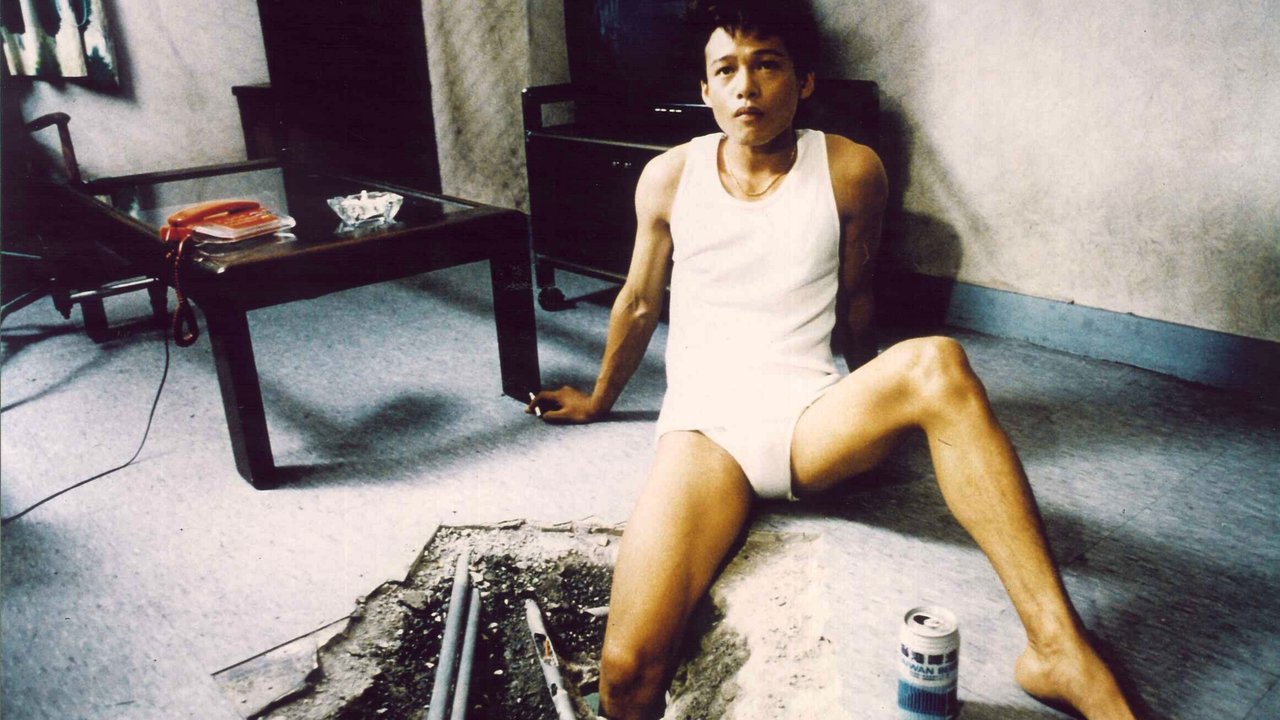

Set in Taiwan just days before the year 2000, a mysterious virus – dubbed the "Taiwan Virus" – grips the city. Symptoms include flu-like conditions, fatigue, and eventually, a bizarre compulsion to crawl on all fours like a cockroach. Residents are urged to evacuate affected areas, but some remain, either through defiance or neglect. Among them are two unnamed residents of a crumbling apartment building: an aloof young man (Lee Kang-sheng, Tsai’s career-long muse) who runs a sparsely stocked grocery stall on the ground floor, and a lonely woman (Yang Kuei-mei, another Tsai regular, who also starred with Lee in Tsai's earlier Vive L'Amour) living directly below him. Their building is dilapidated, leaky, and largely deserted, save for them and the relentless downpour outside.

The catalyst for their strange, minimal interaction? A plumber, sent to investigate a leak, leaves an unfinished hole in the man's floor, directly connecting his apartment to the woman's ceiling below. This physical rupture becomes the film's central metaphor – a crude, accidental conduit through the concrete and isolation separating these two souls. What unfolds isn't a conventional narrative, but a study in loneliness, unspoken desire, and the bizarre ways human connection (or the longing for it) can manifest under extreme duress.

Wordless Worlds, Sudden Song

Fans of Tsai Ming-liang will recognise his signature style immediately. Dialogue is sparse, almost non-existent. Communication happens through coughs, gestures, the dull thud of objects dropped through the hole, the shared misery of leaky pipes and spoiled food. Tsai forces us to watch, to observe the mundane details of these characters’ constrained lives. Lee Kang-sheng, as always, delivers a performance of profound stillness and subtle shifts in expression; his character is often frustratingly passive, yet Lee imbues him with a palpable sense of ennui and simmering desperation. Yang Kuei-mei is equally compelling as the woman downstairs, oscillating between fear, frustration, and a hesitant curiosity towards the man above and the strange portal linking them. Their interactions are fraught with tension, suspicion, and flickers of something akin to intimacy, all conveyed with minimal words.

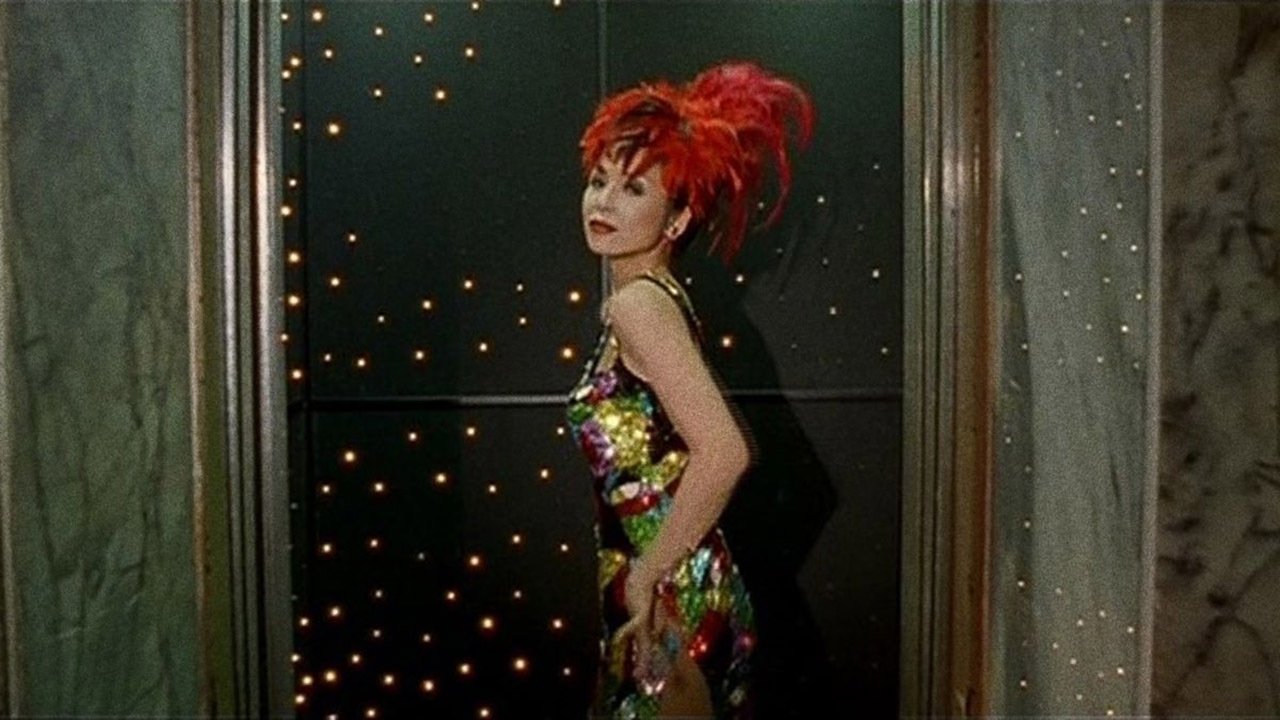

And then, suddenly, there are the musical numbers. Out of nowhere, Yang Kuei-mei transforms, lip-syncing and dancing with surprising abandon to buoyant, classic Mandarin pop songs by Grace Chang from the 50s and 60s. These sequences, bursting with colour and energy, are utterly jarring against the film's bleak, waterlogged backdrop. Are they escapist fantasies? Expressions of repressed desire? It's never explicitly stated, adding another layer to the film's enigmatic quality. They provide moments of surreal levity, but also highlight the profound disconnect between inner longings and external reality. This stark contrast feels deliberate, a hallmark of Tsai's willingness to play with tone and expectation.

Retro Fun Facts

- The Hole wasn't just a standalone project; it was commissioned as part of a French television initiative called "2000, Seen By..." where ten international filmmakers were asked to create a film reflecting on the approaching millennium. This context adds weight to the film's themes of societal anxiety and uncertain futures.

- Filming in such a genuinely dilapidated and constantly wet environment presented unique challenges. Tsai often uses real, functioning decay in his locations, and the constant presence of water – leaking, dripping, pouring – is both a thematic element and a logistical reality of the shoot. Imagine the continuity challenges!

- Despite its challenging nature, the film garnered significant critical acclaim, competing for the prestigious Palme d'Or at the 1999 Cannes Film Festival. It solidified Tsai Ming-liang's reputation as a major voice in international art cinema, part of the "Second New Wave" of Taiwanese filmmakers.

Beneath the Surface

What does The Hole leave us with? It’s certainly not a feel-good film, nor one that offers easy answers. It’s a potent distillation of urban isolation, the kind that can feel suffocating even when surrounded by millions. The pre-millennial setting resonates with anxieties about societal breakdown and disease (themes that feel eerily prescient now), but the core is timeless: the struggle to connect in a world that often feels designed to keep us apart. The hole itself becomes a complex symbol – is it a violation, an opportunity, a source of fear, or a desperate channel for communication? Perhaps it’s all of these things.

Watching it again now, perhaps on a less-than-pristine transfer that evokes that old VHS feeling, the film's deliberate pace and stark visuals feel even more pronounced against today's hyper-edited media landscape. It demands patience, immersion, and a willingness to sit with discomfort. It’s a reminder of a time when finding truly unique, challenging international films often required a bit more searching, making the discovery feel all the more significant.

Rating: 8/10

The Hole earns its high rating not for conventional entertainment value, but for its artistic boldness, its powerful atmosphere, and its haunting exploration of human solitude. Tsai Ming-liang crafts a singular vision, using minimal narrative and dialogue to evoke profound emotional states. The performances are perfectly pitched to the film's restrained tone, and the unexpected musical numbers add a layer of unforgettable surrealism. It's a challenging film, certainly, and its slow pace won't be for everyone who pops a tape in the VCR looking for straightforward thrills. But for those willing to dive into its damp, melancholic world, it offers a deeply resonant and visually arresting experience that lingers long after the screen goes dark. It forces us to confront the silence, both on screen and perhaps, uncomfortably, within ourselves. What strange connections might we form, or fail to form, when faced with our own kinds of isolation?