The persistent drizzle seems to hang over everything in Tsai Ming-liang’s startling 1992 debut, Rebels of the Neon God (Ching shao nien na cha). It’s not just the literal rain slicking the Taipei streets, reflecting the garish glow of signs and headlights, but a metaphorical dampness that seeps into the lives of its young characters. This wasn't the kind of film you stumbled upon easily back in the heyday of VHS rentals, often tucked away in the "World Cinema" corner, but finding it felt like uncovering a secret transmission from a city, and a generation, adrift. It doesn’t grab you with explosions or quick cuts; instead, it pulls you into its rhythm of quiet desperation and unspoken longing.

### Taipei Blues

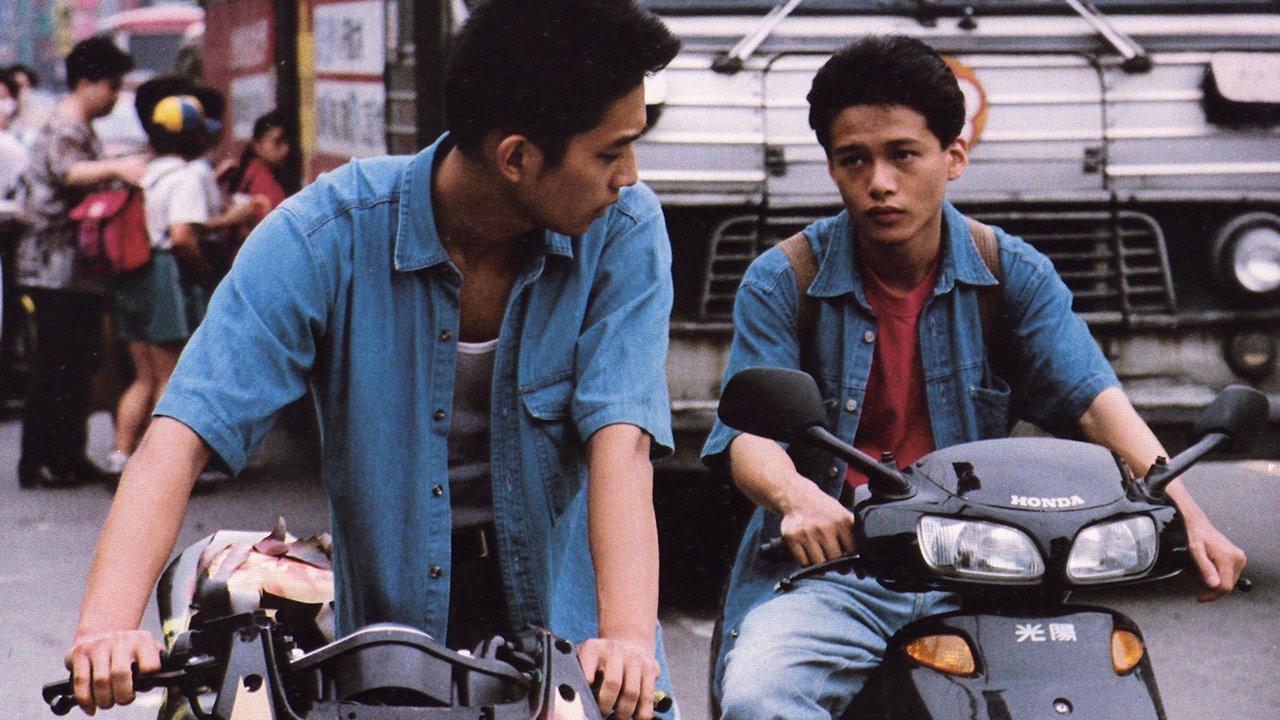

The film ostensibly follows two separate narrative threads that eventually, almost accidentally, intertwine. We meet Hsiao-kang (Lee Kang-sheng), a withdrawn cram school student living with his parents, increasingly convinced by his mother that he is the reincarnation of the vengeful god Nezha. His days are marked by silent observation and simmering frustration, a passive existence punctuated by small acts of rebellion. Elsewhere in the city, two petty thieves, Ah-tze (Chen Chao-jung) and Ah-ping (Jen Chang-bin), drift through arcades, cheap motels, and nighttime streets, trying to hustle enough cash to get by, their boredom occasionally pierced by moments of reckless bravado or fleeting connection, particularly involving Ah-tze’s tentative relationship with Ah-kuei (Wang Yu-wen). There's no grand plot here, just fragments of lives lived under the neon haze, paths crossing with little fanfare but significant consequence.

### The Birth of a Style

Watching Rebels of the Neon God now, it’s fascinating to see the seeds of Tsai Ming-liang’s distinct cinematic language already firmly planted. Known later for masterpieces like Vive L'Amour (1994) and The River (1997), Tsai establishes his signature style right out of the gate: the patient, often static long takes that force us to simply be with the characters in their environments; the sparse dialogue that emphasizes loneliness and the difficulty of communication; the recurring motif of water, often stagnant or flooding, mirroring the characters’ emotional states; and the focus on the textures and sounds of urban life – the hum of traffic, the clatter of arcade machines, the ever-present rain. It’s a world away from the hyperactive editing and storytelling prevalent in much of early 90s cinema, demanding a different kind of attention from the viewer. This wasn't just a stylistic choice; it often stemmed from necessity. Made on a relatively low budget, the film embraces a certain rawness that enhances its realism.

### An Unlikely Icon

Central to Tsai's vision, both here and in almost all his subsequent films, is Lee Kang-sheng. The story of their meeting is legendary among cinephiles: Tsai reportedly discovered the young Lee hanging out, perhaps playing video games, in an arcade hall in Taipei. There was something in his stillness, his seemingly impassive gaze, that captivated the director. Lee isn’t a conventionally expressive actor; his power lies in his presence, his ability to convey deep wells of angst and alienation through subtle shifts in posture or a lingering look. As Hsiao-kang, he embodies the film’s core feeling of being disconnected, observing the world through windows – literal and metaphorical – unable or unwilling to fully engage. It's a performance of remarkable restraint, setting the stage for one of modern cinema’s most enduring director-actor collaborations. Counterpointing Lee's quiet intensity is Chen Chao-jung as Ah-tze, bringing a restless energy, a kind of performative cool that masks his own vulnerability.

### Echoes of Discontent

What makes Rebels of the Neon God resonate, even decades later? It captures a specific kind of youthful malaise, that feeling of being adrift in a world that seems indifferent, full of noise but lacking meaningful connection. The "neon god" of the title isn't just the mythological reference to Nezha; it feels like a nod to the overwhelming, impersonal glow of modernity itself, under which these young people struggle to define themselves. Their acts of rebellion – vandalism, petty theft, skipping school – feel less like calculated defiance and more like desperate attempts to leave some mark, any mark, on a world that threatens to swallow them whole. Does their frustration echo feelings we still grapple with today, surrounded by different kinds of screens and stimuli but perhaps facing similar challenges in finding authentic connection?

The film's pacing can be challenging, its narrative elliptical. It doesn't offer easy answers or neat resolutions. Yet, there's a profound honesty in its depiction of boredom, loneliness, and the tentative search for belonging. I remember first seeing this on a worn-out tape, the slightly degraded image quality somehow adding to the film’s gritty atmosphere. It felt like peering into a hidden corner of the world, far removed from the glossy fantasies Hollywood was offering.

Rating: 8.5/10

This rating reflects the film's undeniable artistic merit, its atmospheric power, and its significance as Tsai Ming-liang's striking debut. The performances, particularly from Lee Kang-sheng, are perfectly attuned to the director's vision. It's a demanding film, its slow pace and bleak outlook won't be for everyone, preventing a higher score for general accessibility. However, for its unflinching portrayal of urban alienation and the birth of a unique cinematic voice, it remains a crucial piece of 90s world cinema.

Rebels of the Neon God doesn't just linger; it permeates, like the damp Taipei air it so vividly captures, leaving you with haunting images and the quiet ache of its characters' solitude long after the screen goes dark. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most rebellious act is simply enduring.