Sometimes, a film doesn't grab you with explosions or frantic chases, but with the quiet, unyielding force of conviction. I remember finding David Mamet's 1999 adaptation of The Winslow Boy nestled on the rental shelf, perhaps looking a bit distinguished, a bit out of place amongst the louder fare of the late 90s. Mamet, the master of jagged, modern dialogue – think Glengarry Glen Ross (1992) or Wag the Dog (1997) – tackling a classic Terence Rattigan play set in Edwardian England? It felt like an intriguing mismatch, the kind of cinematic curiosity that video stores were perfect for uncovering. What unfolds, however, is a masterclass in restraint, a precisely crafted drama that examines the staggering cost of principle.

A Matter of Honour

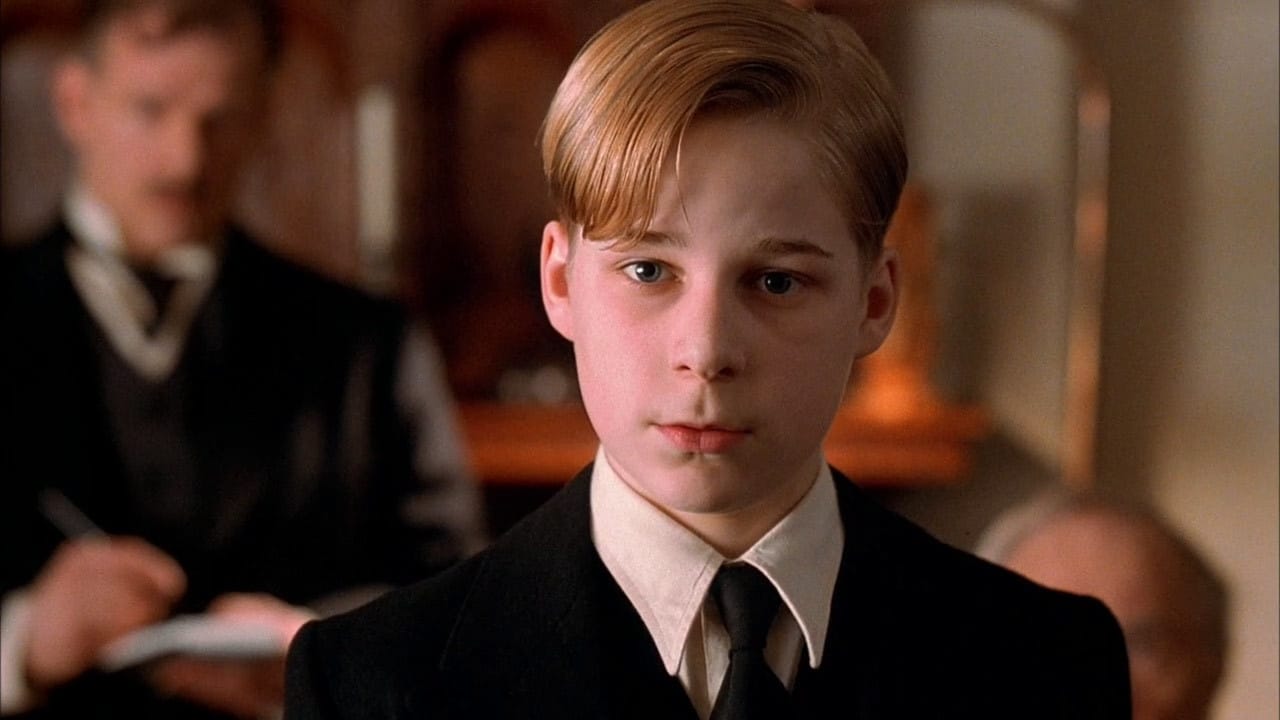

The premise is deceptively simple, yet ripples outwards with devastating consequence. Arthur Winslow (Nigel Hawthorne), a retired bank employee living comfortably in 1912 London, receives word that his 14-year-old son, Ronnie, has been expelled from the Royal Naval College, accused of stealing a five-shilling postal order. Ronnie insists on his innocence. Believing his son, Arthur embarks on a seemingly impossible quest: to clear the boy's name against the monolithic indifference of the Admiralty and the Crown. What begins as a father's defense escalates into a cause célèbre, a public battle fought in the newspapers and, eventually, the hallowed halls of Parliament, under the banner "Let Right Be Done."

Mamet, rather unexpectedly, doesn't try to impose his signature linguistic style onto Rattigan's eloquent, perfectly measured prose. Instead, he directs with a kind of respectful classicism. The camera observes, often holding on faces, allowing the weight of unspoken emotions and societal pressures to build within the meticulously recreated period setting. The film has a tangible atmosphere – the gaslit interiors, the formal manners, the sense of a world operating under rigid codes of conduct, where reputation is paramount. It’s a stark contrast to the typical high-octane energy we often chased on VHS, but its quiet intensity is utterly absorbing.

The Weight of Conviction

At the heart of the film lies the monumental performance of Nigel Hawthorne. Fresh off his acclaimed turn in The Madness of King George (1994), Hawthorne embodies Arthur Winslow not as a fiery crusader, but as a man of quiet, almost terrifying resolve. You see the toll the battle takes – his failing health, the family's dwindling finances, the strain on his marriage to the increasingly worried Grace (Gemma Jones). Yet, his belief in his son, and perhaps more profoundly, in the principle of justice itself, remains unwavering. Hawthorne conveys this complex mixture of frailty and formidable inner strength with breathtaking subtlety. Is his quest noble, or a form of destructive obsession? The film wisely leaves room for the viewer to ponder that very question.

Equally compelling is Jeremy Northam as Sir Robert Morton, the brilliant, highly sought-after barrister and MP who agrees to take the case. Initially, Morton appears aloof, almost disdainful, his cross-examination of young Ronnie feeling clinical and harsh. Northam plays him with a fascinating ambiguity; is he driven by genuine belief, political opportunism, or the intellectual challenge? His verbal sparring matches with Arthur's daughter, Catherine (Rebecca Pidgeon), crackle with intelligence and unspoken attraction. Northam masterfully reveals the layers beneath Morton's icy facade, culminating in moments where his own deeply held principles unexpectedly surface.

A Suffragette's Sacrifice

Rebecca Pidgeon (Mamet's wife, cast here with perfect understanding of the character's intellect) shines as Catherine. A committed suffragette, intelligent and independent, Catherine initially views her father's crusade with skepticism, fearing its impact on the family and her own engagement to a dependable, if unexciting, army captain. Yet, as the case progresses, she becomes its staunchest supporter, sacrificing her personal happiness for the principle her father champions. Pidgeon portrays Catherine's journey with quiet dignity and resolve, embodying the era's burgeoning feminist spirit constrained by societal expectations. Her evolving relationship with Sir Robert Morton forms one of the film's most intriguing undercurrents.

Echoes of Truth and Craft

It adds another layer of resonance to know that Rattigan's 1946 play was inspired by a real-life case – that of George Archer-Shee, a naval cadet similarly accused in 1908, whose father also fought relentlessly for his exoneration, aided by the formidable barrister Sir Edward Carson. Mamet, filming primarily in London and Shepperton Studios, honors this historical weight. He doesn't rush; he lets scenes unfold, trusting the power of Rattigan's dialogue and the actors' calibrated performances. The deliberate pacing feels less like a flaw and more like an invitation to truly listen, to absorb the nuances of language and the gravity of the stakes. It's a reminder that cinematic tension doesn't always require speed; it can be built through meticulous detail and simmering emotion. Watching it now, it feels like a beautifully crafted artifact, a testament to intelligent screenwriting and superb acting, qualities that perhaps felt even more precious when discovered amidst the more ephemeral trends of the late 90s rental scene.

Rating: 9/10

The Winslow Boy is a triumph of intelligence and restraint. Mamet's respectful direction allows Rattigan's superb play to shine, anchored by powerhouse performances, particularly from Hawthorne and Northam. It's a film that trusts its audience, delivering profound emotional impact through quiet intensity rather than overt spectacle. The 9 rating reflects its near-flawless execution as a period drama, its compelling exploration of justice and sacrifice, and the sheer brilliance of its central performances. It might not have been the loudest tape on the shelf, but its story resonates with a timeless, quiet power.

What endures most, perhaps, is the unsettling question it leaves us with: How much should one be willing to sacrifice for the sake of principle, especially when the cost is borne not just by oneself, but by everyone they love?