There’s a certain sun-bleached grittiness to Sydney, a kind of laid-back menace that few films capture quite like Gregor Jordan’s 1999 debut, Two Hands. It arrived near the tail-end of the VHS era, a tape box that might have initially seemed like just another quirky crime flick amidst the Lock, Stock-inspired wave. Yet, picking it up from the local Video Ezy (or Blockbuster, depending on your side of the Pacific) revealed something uniquely Australian, a darkly comic thriller simmering with sweat, desperation, and the undeniable spark of a young star about to explode onto the world stage.

Kings Cross Calling

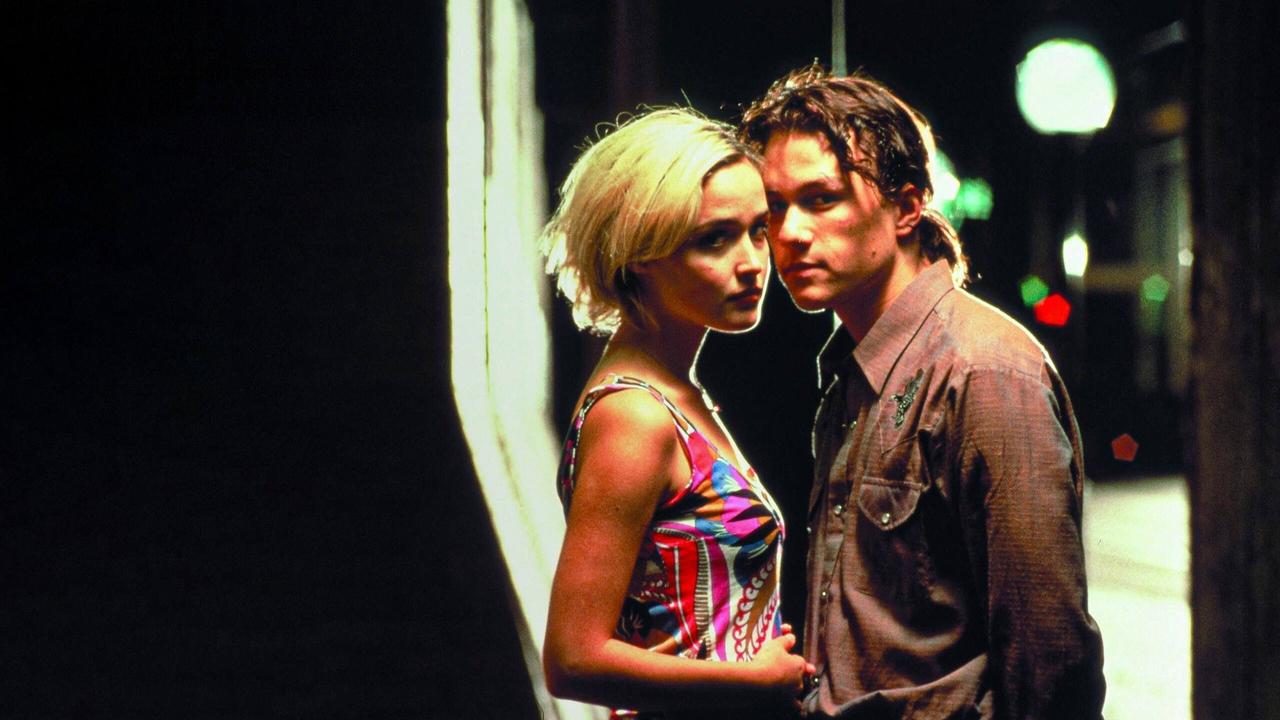

The film throws us headfirst into the life of Jimmy, played with an utterly magnetic, raw charisma by a then 19-year-old Heath Ledger. Jimmy’s not a criminal mastermind; he’s a naive strip club tout in Sydney’s notorious Kings Cross district, trying to make a quick buck. When local crime boss Pando (Bryan Brown, radiating effortless Aussie cool and coiled-spring danger) gives him a simple delivery task – drop off $10,000 – things immediately, almost comically, go wrong. A distracting encounter on Bondi Beach, a couple of opportunistic kids, and suddenly Jimmy owes a very dangerous man a lot of money he doesn’t have. What follows is a frantic scramble through Sydney’s underbelly, a blend of ill-conceived robberies, dodgy deals, and burgeoning romance with the sweet, slightly more grounded Alex (Rose Byrne, already showing the intelligence and charm that would define her career).

What sets Two Hands apart immediately is its tone. Gregor Jordan, who both wrote and directed, masterfully walks a tightrope between genuine threat and offbeat humour. The violence, when it comes, is often abrupt and shocking, grounding the film in a harsh reality. Yet, moments later, we might find ourselves chuckling at the sheer absurdity of Jimmy's predicament or the quirky personalities orbiting Pando's world. Jordan apparently drew inspiration from tales he'd heard growing up, including one about a hapless fellow losing mob money, lending the narrative a slightly mythic, urban legend quality despite its contemporary setting. It’s a testament to his script and direction that these tonal shifts feel organic rather than jarring.

The Spark Before the Flame

You simply can't discuss Two Hands without focusing on Heath Ledger. This was the same year 10 Things I Hate About You introduced him to international audiences as a charming heartthrob, but Two Hands showcased a different, arguably deeper, facet of his talent. His Jimmy is instantly likeable, even sympathetic, despite his poor choices. There’s a vulnerability beneath the attempted swagger, a boyishness that makes his descent into the criminal world feel both tragic and believable. Watching it now, knowing the incredible heights his career would reach before its tragic end, lends the viewing an extra layer of poignancy. You see the raw materials here – the screen presence, the expressive eyes, the ability to convey complex emotions with seeming ease. It’s a performance brimming with the promise of greatness.

Alongside him, Bryan Brown is perfectly cast. Pando isn't a raving lunatic; he's pragmatic, almost avuncular in his menace, which somehow makes him even more intimidating. He represents the ingrained, almost casual nature of organised crime in this world. Brown, a veteran of Australian cinema already well-known internationally from films like Cocktail (1988) and F/X (1986), won the AFI Award (Australian Film Institute) for Best Actor for this role, one of five awards the film scooped up, including Best Film, Best Director, and Best Original Screenplay – a remarkable achievement for a debut feature made on a relatively modest budget of around $3.6 million AUD.

Sun, Surf, and Supernatural?

Adding another layer to the film's unique flavour is the recurring appearance of Jimmy's deceased older brother, Michael (Steven Vidler), acting as a sort of spectral guardian angel or perhaps just a manifestation of Jimmy's conscience and fear. It’s an unexpected, slightly whimsical element that could have easily felt out of place. Yet, Jordan integrates it seamlessly, adding a touch of melancholy and reinforcing the themes of fate and family loyalty that run beneath the surface. It's one of those narrative choices that elevates Two Hands beyond a standard crime caper.

Filmed predominantly on location, the movie uses Sydney, particularly the infamous Kings Cross and the iconic Bondi Beach, not just as a backdrop but as a character. The bright sunshine often contrasts sharply with the darkness of the events unfolding, creating a distinct visual identity. Combine this with a killer soundtrack heavily featuring Aussie rock legends Powderfinger (whose track "These Days" became indelibly linked with the film), and you have an experience that feels authentically Australian to its core. It captures a specific time and place with uncanny accuracy, a snapshot of late-90s Sydney life, warts and all.

Why It Still Holds Up

Rewatching Two Hands today, perhaps on a format far removed from the worn VHS tape I first saw it on, its strengths remain clear. The sharp dialogue, the confident direction, the perfect tonal balance, and crucially, the stellar performances led by a young Ledger on the cusp of stardom. It avoids easy categorisation – it's funny, it's tense, it's violent, it's surprisingly moving. It’s a reminder of a time when Australian cinema was consistently producing unique, character-driven genre films that could stand confidently alongside their international counterparts. It might not have had the immediate global impact of some contemporaries, but its reputation as a cult classic is thoroughly deserved.

Rating: 8/10

The rating reflects a film that achieves exactly what it sets out to do, delivering a smart, stylish, and engaging crime story with exceptional performances and a distinct sense of place. The blend of dark comedy and genuine thrills is expertly handled, and Ledger's early brilliance is captivating. It’s a standout piece of 90s Australian cinema that still feels fresh and vital. For fans of crime thrillers with a unique voice, or anyone wanting to witness the nascent talent of Heath Ledger, Two Hands is essential viewing – a sun-drenched noir that leaves a lasting impression long after the credits roll. What lingers most, perhaps, is the feeling of potential – both Jimmy's potential for escape, and Ledger's potential, so brilliantly hinted at here, for cinematic immortality.