Okay, let's settle in. Sometimes a movie arrives not with the usual Hollywood fanfare, but more like a whispered legend passed between those in the know. It might have started life elsewhere – on stage, perhaps, or even flickering across television screens before finding its way onto that coveted VHS tape (or, admittedly, a very early DVD in this case). Such is the delightful journey of O Auto da Compadecida, known to many of us simply as A Dog's Will (2000), a film that feels both utterly unique and comfortably familiar, like a folk tale brought vividly to life. It originally graced Brazilian television as a four-part miniseries in 1999, a format that perhaps primed it perfectly for the intimate experience of home viewing, before being deftly edited into the cinematic gem we cherish. Doesn't that origin story already hint at something special, something crafted with a different rhythm?

### Sunshine, Scoundrels, and the Sertão

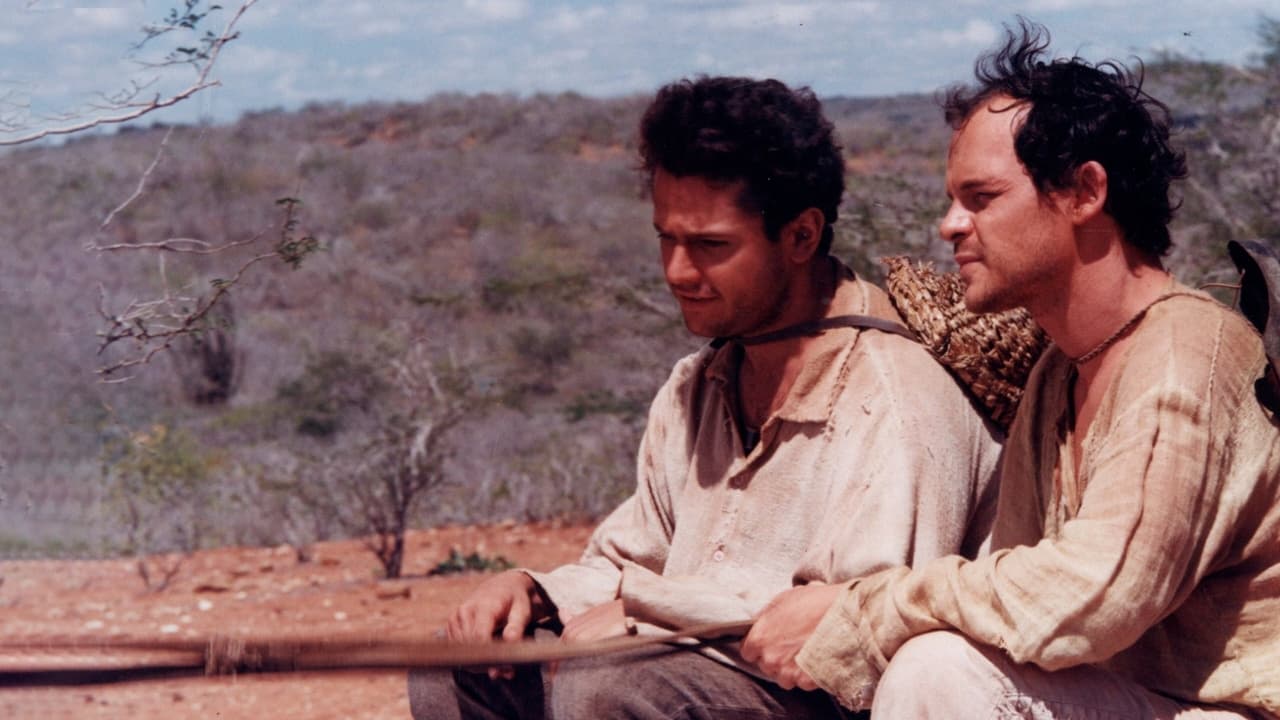

The film throws us headfirst into the arid, sun-baked landscape of the Brazilian Sertão in the 1930s, a place where life is hard, faith is fervent, and ingenuity is the currency of survival. Our guides through this vibrant, often absurd world are two unforgettable companions: the perpetually scheming, fast-talking João Grilo, brought to life with electric energy by Matheus Nachtergaele, and his more cowardly, romantically inclined sidekick Chicó, played with perfect comedic timing by Selton Mello. Their chemistry is immediate and infectious. João Grilo isn't malicious, not really; he's a survivor, a trickster figure straight out of folklore, using his sharp wit to navigate the hypocrisies of the church, the wealthy landowners, and the fearsome local bandits (cangaceiros). Chicó, often swept along by João's schemes, grounds the fantastical with his wide-eyed reactions and his own penchant for wildly exaggerated tales, especially concerning his romantic conquests. Remember Chicó’s insistence he once encountered a screech owl that spoke Latin? It’s precisely this blend of the earthy and the outlandish that gives the film its unique flavour.

The narrative unfolds episodically, much like the oral traditions it draws upon. We follow João and Chicó through a series of hilarious and increasingly precarious situations – attempting to secure a church blessing for a dog, navigating local power struggles, dealing with the fearsome bandit Severino de Aracaju (Marco Nanini), and ultimately facing a judgment far more final than any earthly court. Director Guel Arraes, alongside writers Adriana Falcão and João Falcão, masterfully adapts Ariano Suassuna's beloved 1955 play, preserving its sharp social satire and rich linguistic humour while translating it into a visually captivating cinematic experience. Suassuna, a celebrated figure in Brazilian literature, aimed to create an "armorial art" – art rooted deeply in the popular culture and traditions of Northeast Brazil – and this film feels like its triumphant realization on screen.

### Laughter in the Face of Mortality

What elevates A Dog's Will beyond mere comedy is its profound engagement with themes of faith, justice, and the human condition. The humour isn't just for laughs; it's a tool to expose the greed, corruption, and hypocrisy João Grilo encounters, particularly within the local church hierarchy. The town's priest (Rogério Cardoso) and bishop (Lima Duarte) are hilariously depicted as more concerned with status and wealth than spiritual guidance, providing ample targets for João's cunning manipulations. Yet, the film never feels cynical. There's a deep affection for its characters, even the flawed ones, and a genuine exploration of spiritual questions.

This culminates in the film's famous climax: a divine judgment scene where João, Chicó, the priest, the bishop, the baker, and his wife find themselves pleading their cases before Jesus (Maurício Gonçalves), the Devil (Luís Melo), and, crucially, the Virgin Mary, portrayed with serene authority by the legendary Fernanda Montenegro. Montenegro's casting was a masterstroke; bringing Brazil's most revered actress into this pivotal role lends immense weight and warmth to the proceedings. This scene is a brilliant blend of farce and profundity. João, naturally, attempts to talk his way out of damnation, employing the same wit he used on Earth, while the Devil presents his cases with bureaucratic relish. It’s Mary, invoked by João as "Our Lady of Compassion" (a literal translation of Compadecida), who ultimately advocates for humanity's inherent fallibility and capacity for good. What does it say about us, the film seems to ask, that our best hope often lies in compassion rather than strict adherence to rules?

### A Modern Folktale

Technically, the film is a delight. The production design perfectly captures the dusty, vibrant atmosphere of the Sertão. The cinematography balances the harsh reality of the environment with moments of almost magical realism. The practical effects, particularly in the judgment scene, possess a charming theatricality that feels perfectly suited to the story's folk-tale roots. It reportedly cost around R$10 million (Brazilian Reais) – a significant budget for Brazilian cinema at the time – largely financed by Globo Filmes based on the massive success of the miniseries, which drew huge audiences. Its transition to the big screen was equally triumphant, becoming one of Brazil's highest-grossing films.

Watching it today, it doesn’t feel dated. Its humour remains sharp, its characters endearing, and its themes universal. It's a reminder that great storytelling often comes from specific cultural contexts yet speaks to something fundamental in all of us. It taps into that same vein of witty, character-driven comedy mixed with poignant observation that we might find in certain Ealing comedies or the works of Preston Sturges, yet filtered through a uniquely Brazilian lens.

---

Rating: 9/10

A Dog's Will earns this high mark for its sheer brilliance in balancing laugh-out-loud comedy with genuine heart and spiritual depth. The performances by Nachtergaele and Mello are iconic, the writing is razor-sharp, drawing beautifully from Suassuna's masterpiece, and the direction captures a unique time and place with vibrancy and wit. Its journey from play to wildly successful TV miniseries to beloved film speaks volumes about its resonant power. It loses perhaps a single point only in that its episodic nature, a holdover from the miniseries, might feel slightly loose compared to tightly plotted features, but this is also part of its distinct charm.

Final Thought: This isn't just a funny movie; it's a warm, wise, and wonderfully humane film that feels like discovering a hidden classic, even if it arrived just as the VHS era was winding down. It leaves you pondering faith, forgiveness, and the undeniable spark of life found in the most unlikely of rogues.