Okay, settle in. Let’s dim the lights, imagine the gentle hum of a CRT, and talk about a film that simmered just below the mainstream radar as the new millennium dawned: Bob Giraldi’s Dinner Rush (2000). It arrived right at that interesting cusp, didn't it? When indie darlings still had a strong presence on video store shelves, just before the full digital wave crashed. Watching it again feels less like pure 80s/90s nostalgia and more like revisiting a forgotten bridge between eras, a film carrying the DNA of 90s independent spirit into the uncertain future of 2000.

A Pressure Cooker of Flavors and Danger

What strikes you immediately about Dinner Rush is its singular focus, its almost theatrical confinement. The entire narrative unfolds over one incredibly tense evening within the walls of Gigino Trattoria, a high-end Italian restaurant in Tribeca, New York City. This isn't just a setting; it's a microcosm. We have Louis Cropa (Danny Aiello), the venerable owner and bookmaker, presiding over his domain like an old-world patriarch. He’s resistant to the nouvelle cuisine experiments of his son, Udo (Edoardo Ballerini), the restaurant's star chef, who views food as high art. Add to this volatile mix Louis's gambling debts, a pair of menacing gangsters lurking at the bar (played with chilling nonchalance by Mike McGlone and John Corbett), a powerful food critic holding court, Wall Street blowhards, an intriguing art gallery owner, and a sous chef named Nicole (Vivian Wu) caught between father and son, and you have a recipe for combustion. The film masterfully uses the contained space to amplify the simmering tensions – personal, professional, and criminal.

The Authenticity on the Plate (and Behind the Camera)

There's a palpable energy to the restaurant scenes, a controlled chaos that feels utterly genuine. And here’s a fantastic piece of insight that explains why: director Bob Giraldi, primarily known before this for legendary music videos like Michael Jackson's "Beat It" and countless high-profile commercials, actually co-owned the real-life Tribeca restaurant, Gigino Trattoria, where the film was shot. Knowing this adds another layer entirely. You can almost feel the crew working within the familiar constraints and possibilities of a space Giraldi intimately understood. It wasn't just a set; it was his place. This wasn't some slick Hollywood production recreating a restaurant; it was a restaurant, temporarily transformed into a film set, likely imbuing the cast and crew with the authentic rhythms and pressures of the environment. It’s this kind of real-world grounding that often elevates these smaller, passionate projects. It feels lived-in because, in a very real sense, it was.

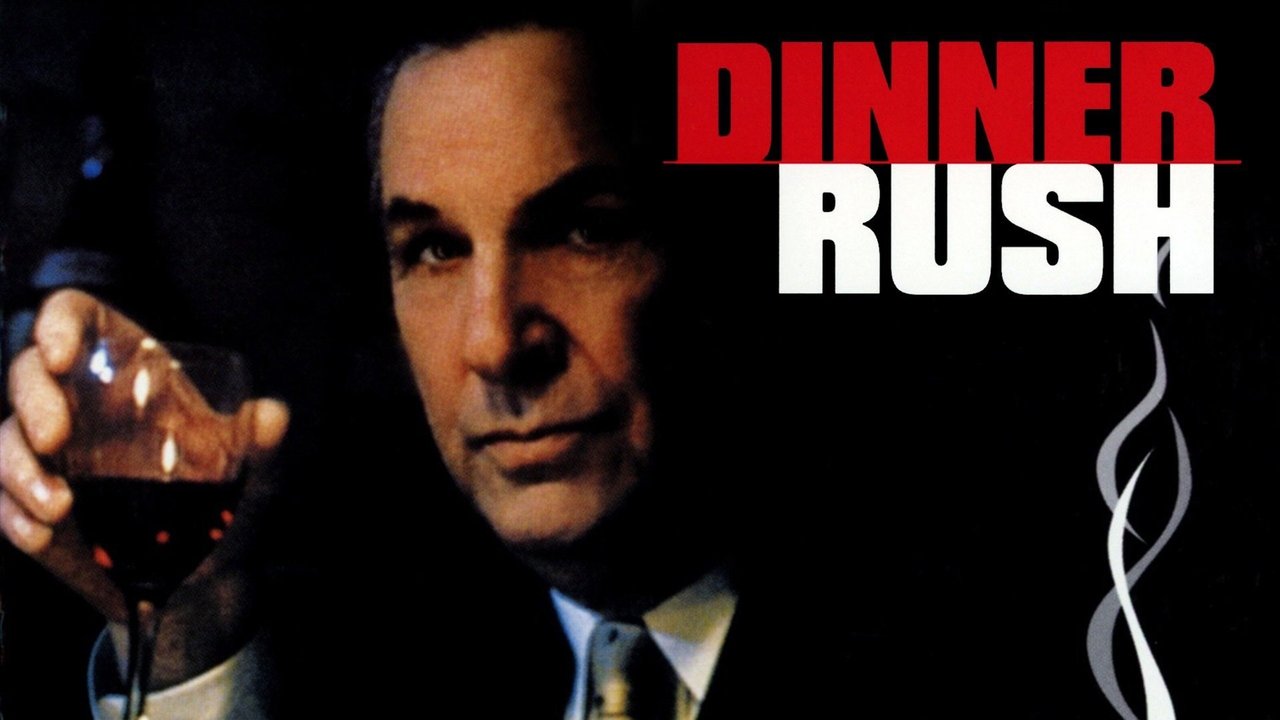

Aiello Anchors the Storm

At the heart of it all is Danny Aiello. Released just over a decade after his Oscar-nominated turn in Spike Lee's Do the Right Thing (1989), Aiello brings a weary gravitas to Louis Cropa. He’s a man caught between eras – the old neighborhood ways clashing with the sophisticated, high-stakes world his son embraces. Aiello embodies this conflict beautifully; his performance isn't flashy, but it's deeply felt. You see the pride, the worry, the quiet calculation behind his eyes. He’s the anchor, the traditional center around which the modern chaos swirls. His interactions with Edoardo Ballerini's Udo crackle with the friction of generational misunderstanding and unspoken love. Ballerini, for his part, perfectly captures the intense, almost obsessive passion of a chef pushing creative boundaries, often oblivious to the more dangerous currents swirling around him. And Vivian Wu provides a steady, watchful presence, navigating the complex dynamics with quiet strength.

More Than Just Food and Felons

While the gangster subplot provides the film's thrilling spine, Dinner Rush uses it to explore richer themes. It's about the tension between tradition and innovation – not just in cuisine, but in life. Can the old ways survive? Must they adapt? It delves into the nature of art, questioning whether Udo's meticulous creations are fundamentally different from the paintings discussed by the gallery owner (Sandra Bernhard, in a memorable cameo). The film doesn’t offer easy answers, instead letting these questions hang in the air, mingling with the aromas from the kitchen and the scent of danger from the bar. It’s a surprisingly layered piece, using the specifics of one night in one place to ask broader questions about legacy, family, and the price of ambition. Doesn't the contained pressure of that single night feel symbolic of the pressures we all face, juggling personal histories with future aspirations?

A Taste Worth Savoring

Dinner Rush isn't a blockbuster, nor does it try to be. It's a character-driven piece, a slow burn that relies on atmosphere, sharp dialogue, and compelling performances. Giraldi’s direction is confident, making the most of the single location, using fluid camera movements to navigate the bustling dining room and frantic kitchen. It’s a film that feels handcrafted, a passion project that benefits immensely from its grounded setting and the authenticity brought by its cast, especially Aiello. It might have slipped under the radar for some back in 2000, perhaps overshadowed by bigger studio releases or lost in the shuffle between the fading VHS era and the rise of DVD. But revisiting it now feels like rediscovering a hidden gem.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's exceptional atmosphere, Danny Aiello's superb central performance, the clever use of a single location, and its engaging blend of culinary drama and crime thriller elements. It successfully creates a palpable sense of time and place, weaving its various plot threads together into a tense, satisfying whole. While perhaps not revolutionary, it executes its premise with considerable skill and heart, elevated by that authentic sense of place thanks to Bob Giraldi shooting in his own restaurant.

Dinner Rush remains a compelling snapshot of a specific time and place, a flavorful indie film that lingers long after the credits roll, much like the memory of a truly exceptional meal. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the most intense dramas unfold not on grand battlefields, but across the tables and behind the kitchen doors of a neighborhood restaurant.