The sterile white corridors stretch endlessly, punctuated only by the rhythmic beep of unseen machines and the hushed, hurried footsteps of those who hold life and death in their hands. But what if the sanctuary becomes the source of the terror? What if the healers are the harbingers of something far worse than illness? This is the icy premise anchoring Michael Crichton's 1978 thriller, Coma, a film that trades jump scares for a creeping, clinical dread that settles deep in your bones.

### Anesthesia and Unease

Based on Robin Cook's bestseller (though Crichton adapted his own screenplay from it, adding his distinct touch), Coma taps into a primal fear: the ultimate vulnerability of being unconscious on an operating table. We follow Dr. Susan Wheeler (Geneviève Bujold), a sharp, observant surgical resident at Boston Memorial Hospital. When her best friend, Nancy Greenly (Lois Chiles, whom many will remember from Moonraker the following year), falls into an inexplicable coma after a routine procedure, Susan starts asking questions. Soon, she uncovers a disturbing pattern – a disproportionately high number of young, healthy patients suffering the same fate. Her concerns are initially dismissed, particularly by her ambitious boyfriend, Dr. Mark Bellows (Michael Douglas, still riding high from TV's The Streets of San Francisco and his Oscar win for producing One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest), and the hospital's imposing Chief of Surgery, Dr. George Harris (Richard Widmark). But Susan's persistence pushes her down a rabbit hole of conspiracy that feels chillingly plausible.

### The Crichton Factor

Michael Crichton, leveraging his own Harvard medical background, directs with a terrifyingly detached precision. He understood the inherent drama and fear within the hospital environment – the jargon, the procedures, the power dynamics, the life-and-death stakes. This wasn't just science fiction; it felt grounded, possible. Crichton reportedly insisted on a high degree of medical accuracy, even hiring doctors as consultants and extras, lending the film an unsettling authenticity that elevates the suspense. The sterile production design, often utilizing real hospital locations, becomes a character itself – cold, indifferent, and vast enough to hide the darkest secrets. Jerry Goldsmith's score is equally masterful, avoiding typical horror cues for discordant, unnerving strings that perfectly mirror Susan's fraying nerves and the film's pervasive sense of paranoia.

### A Conspiracy Unveiled

Geneviève Bujold is the beating heart of Coma. Her performance is a masterclass in controlled panic escalating into sheer terror. She portrays Susan not as a damsel in distress, but as an intelligent, capable professional increasingly isolated and gaslit by the very institution she serves. You feel her frustration, her fear, her dawning horror as the pieces click into place. It’s a compelling, believable portrayal of quiet determination against overwhelming, insidious forces. It’s worth noting Bujold was reportedly hesitant about the role, initially finding the subject matter too grim, but Crichton convinced her, and it remains one of her most memorable performances. Douglas provides solid support as the initially skeptical, then concerned boyfriend, representing the audience's own journey from disbelief to dawning realization.

The film builds its tension slowly, methodically. It's less about sudden shocks and more about the suffocating atmosphere of doubt and the growing certainty that something is terribly wrong. Who can Susan trust? The walls feel like they're closing in, not just metaphorically but literally, within the labyrinthine hospital corridors and the shadowy offices of its administrators. This slow burn culminates in the film's most iconic and deeply disturbing sequence: Susan's infiltration of the infamous Jefferson Institute.

### The Jefferson Institute: Nightmare Fuel

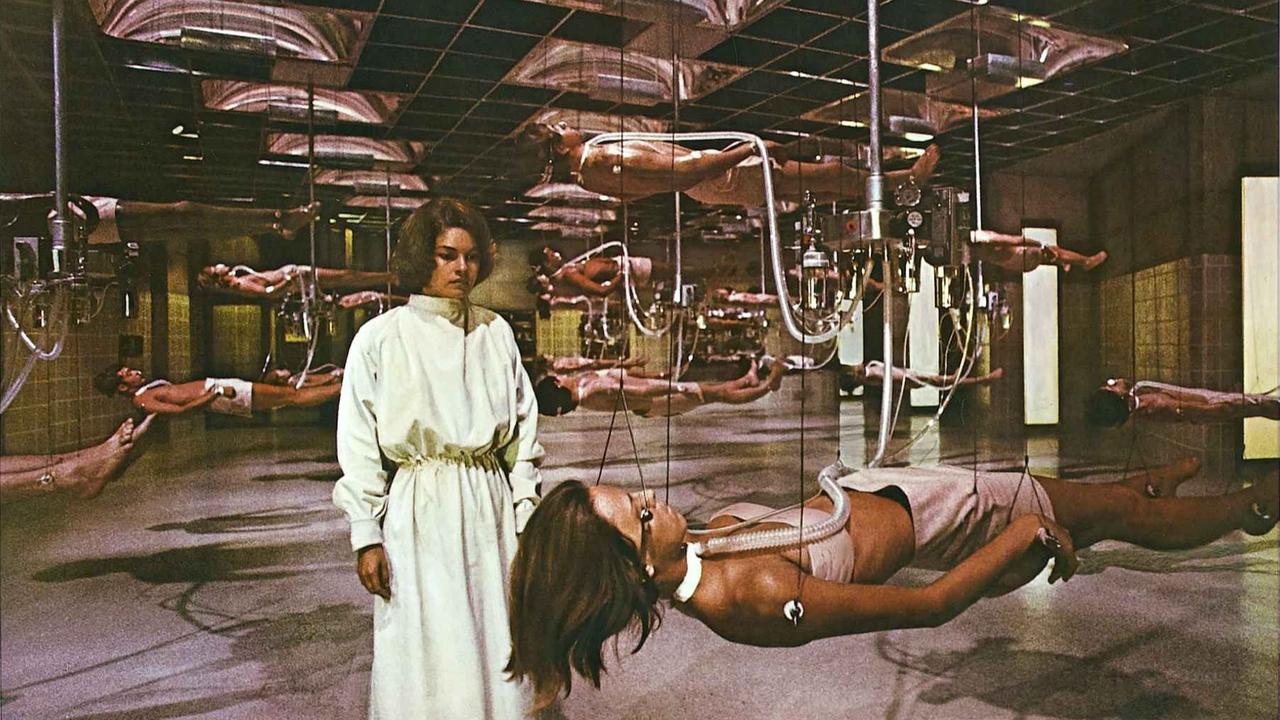

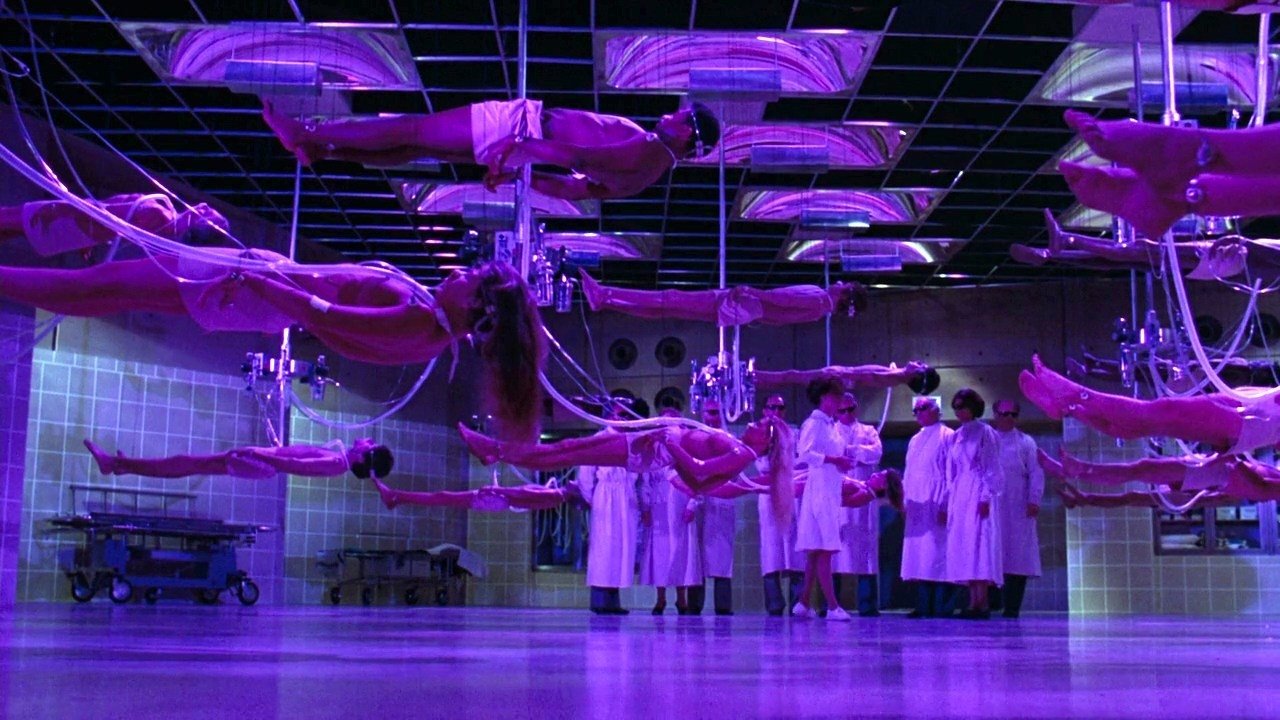

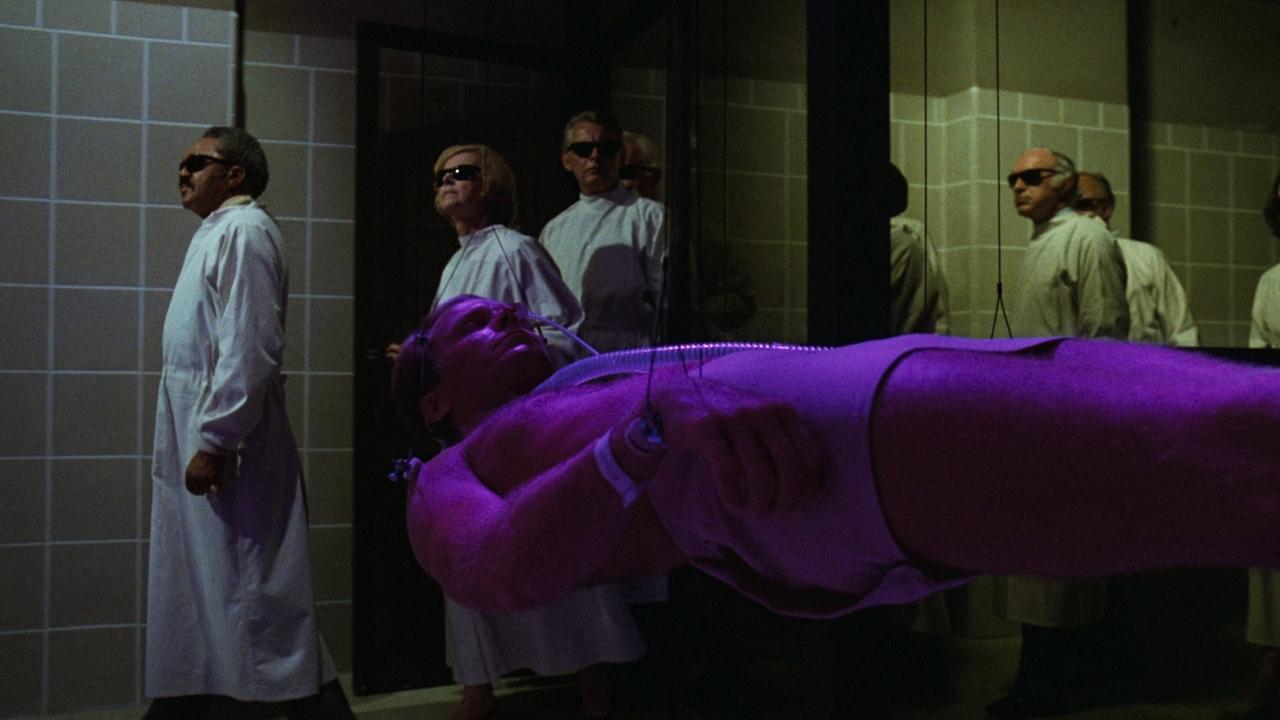

(Minor Spoilers Ahead for a 45-year-old film!) The reveal of the Jefferson Institute remains one of the most chilling set pieces in 70s cinema. The sight of dozens of comatose bodies suspended by wires, perfectly preserved and seemingly floating in a vast, sterile chamber, is pure nightmare fuel. Crichton films this with a horrifying matter-of-factness. The practical effects used to achieve this (bodies suspended from tracks hidden above, filmed through diffusion filters) might seem dated by CGI standards, but their tangible reality retains a visceral power. There’s a cold, industrial logic to the horror that is far more unsettling than any monstrous creature. This sequence was apparently quite challenging to film, requiring intricate wire work and careful choreography to create the illusion of effortless suspension. The result is unforgettable, a truly ghastly vision of dehumanization presented with chilling detachment. (Spoilers End)

### Lasting Effects and Retro Realities

Coma was a significant box office success, grossing around $50 million on a modest $4.1 million budget (that's roughly $230 million against $19 million today – a bona fide hit!). It tapped into contemporary anxieties about medical ethics, organ transplantation (a relatively new field then), and the potential for institutional corruption. Its influence can be seen in countless medical thrillers that followed, but few captured its specific blend of procedural detail and existential dread so effectively. Watching it today, especially on a slightly fuzzy VHS transfer back in the day, heightened that sense of unease – the sterile blues and greens of the hospital palette felt colder, the shadows deeper, the isolation more profound on a CRT screen late at night. Remember puzzling over the complex plot points, rewinding to catch a clue Susan might have missed?

The film isn't perfect; some plot mechanics require a degree of suspension of disbelief, and a few supporting characters verge on stereotype. But these are minor quibbles in the face of its masterful construction of suspense and atmosphere. It preys on our deepest fears about helplessness and bodily autonomy, making the familiar, trusted environment of a hospital feel alien and threatening.

Rating: 8.5/10

Coma earns its high score through Geneviève Bujold's stellar performance, Michael Crichton's clinically precise direction, its deeply unsettling premise grounded in chilling plausibility, and the unforgettable, disturbing imagery of the Jefferson Institute. It masterfully builds tension through atmosphere and paranoia rather than relying on cheap scares. While firmly rooted in its era, the core fears it exploits remain potent. It stands as a high watermark for the medical thriller genre, a film that proves the most terrifying monsters aren't supernatural beings, but the chilling possibilities lurking within human institutions and the cold calculus of unethical minds. Its power to disturb hasn't faded one bit, a testament to Crichton's skill in transforming a hospital procedural into a descent into genuine horror. It even spawned a less-regarded TV miniseries remake in 2012, proving the enduring resonance of its terrifying concept.