Okay, settle in. Let’s talk about a film that doesn’t just haunt you; it burrows under your skin and stays there, a chilling reminder of how thin the veil is between normalcy and the abyss. Sunlight streams through the car window, the radio plays softly, lovers banter... and then, oblivion. Few films capture the suddenness of disappearance, the mundane horror of a void opening up in broad daylight, quite like George Sluizer's 1988 Franco-Dutch masterpiece, The Vanishing (Spoorloos). Watching this on a rented VHS tape back in the day, probably late at night on a flickering CRT, felt like stumbling upon something genuinely forbidden, profoundly unsettling in a way few thrillers ever manage.

The Void Opens

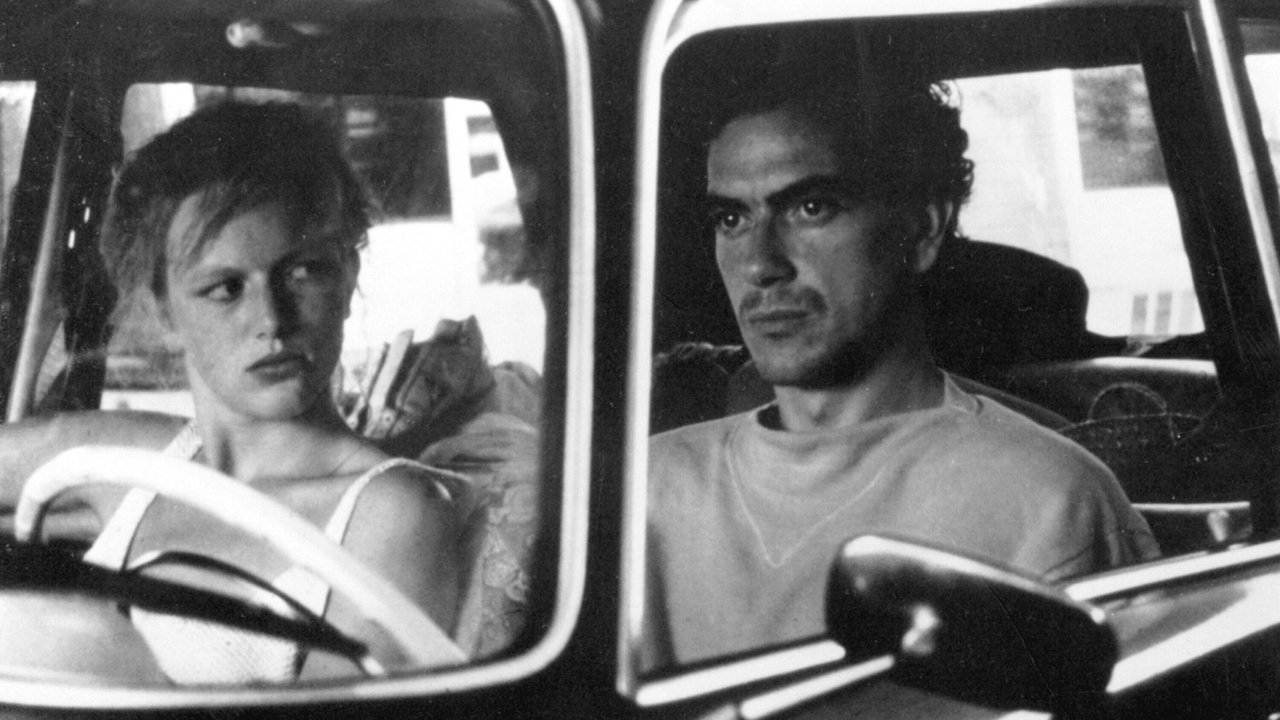

The setup is deceptively simple, almost unnervingly familiar. Rex Hofman (Gene Bervoets) and his girlfriend Saskia Wagter (Johanna ter Steege) are on holiday, driving through France. They stop at a busy service station, argue playfully, make up. Saskia goes to buy drinks... and never returns. What follows isn't a typical frantic police procedural or a high-octane chase. Instead, Sluizer crafts a meticulous, agonizing study of obsession – Rex's relentless, years-long quest not just for answers, but to experience what Saskia experienced. It’s a chillingly passive investigation driven by an internal wound that refuses to heal.

The film masterfully uses the bright, ordinary settings – sun-drenched highways, bustling rest stops, mundane apartments – to amplify the horror. There are no gothic castles or shadowy figures lurking in fog here. The terror lies in its plausibility, in the terrifying idea that evil can wear the most unremarkable face and operate in plain sight. I remember the sheer frustration watching Rex’s search unfold, the leads drying up, the years ticking by. It felt so achingly real, unlike the neat resolutions often served up in Hollywood thrillers.

A Different Kind of Monster

Halfway through, the film makes a bold, brilliant shift in perspective. We meet Raymond Lemorne (Bernard-Pierre Donnadieu), a seemingly ordinary chemistry teacher, husband, and father. And Sluizer shows us, with chilling detachment, exactly who he is and what he did. There's no mystery surrounding the perpetrator's identity, which is precisely the point. The horror deepens as we witness Lemorne’s methodical planning, his "experiments" – not born of rage or frenzy, but of a cold, intellectual curiosity, a horrifyingly logical descent into sociopathy. He wants to know if he is capable of pure evil, treating abduction like a scientific problem to be solved.

Bernard-Pierre Donnadieu's performance is simply unforgettable. He embodies Lemorne with a terrifying banality. There’s no mustache-twirling villainy, just a calm, almost gentle demeanor masking a profound emptiness. His explanations for his actions, delivered with unsettling reasonableness, are perhaps the most disturbing aspect of the film. Apparently, Donnadieu found the role deeply taxing, immersing himself in the chilling mindset of Lemorne – a testament to the power of his portrayal. In contrast, Gene Bervoets delivers a raw, exposed nerve of a performance as Rex. His grief isn't histrionic; it's a slow erosion of his soul, a quiet desperation that makes his ultimate choices both shocking and tragically understandable. And though her screen time is limited, Johanna ter Steege makes Saskia a vibrant, tangible presence, ensuring her absence leaves a palpable void.

From Page to Screen, and the Haunting Echo

Based on Tim Krabbé's novella The Golden Egg, who also co-wrote the screenplay with Sluizer, the film retains the book's bleak, existential dread. It’s a testament to Sluizer’s vision (apparently Stanley Kubrick contacted him after seeing it, calling it the most terrifying film he’d seen – high praise indeed, even if relayed second-hand!) that he resisted any pressure to soften the narrative. Shot on a relatively low budget across locations in France and the Netherlands – that specific TOTAL gas station becoming an unnerving landmark in my mind – the film’s stark realism is part of its power. It doesn't rely on jump scares or elaborate effects; its horror is psychological, existential.

Of course, many will remember the 1993 American remake, also directed by George Sluizer, starring Jeff Bridges, Kiefer Sutherland, and Nancy Travis. While not without its merits (primarily Bridges' performance), it notoriously features a drastically altered, more "Hollywood" ending. Comparing the two provides a stark lesson in artistic compromise versus unflinching vision. The original's ending... well, if you know, you know.

[Spoiler Alert for the ending of the 1988 original]

The climax of the original Vanishing is one of the most audacious and chilling conclusions in cinema history. Rex's desperate need to know, to experience Saskia's fate, leads him to accept Lemorne's horrifying offer. The claustrophobia, the dawning realization, the final darkness – it’s utterly devastating. There's no catharsis, no justice, just the cold, terrifying finality of Lemorne's "perfect" act and Rex's obsession reaching its terrible apotheosis. It’s an ending that doesn’t offer closure but instead leaves you staring into the void alongside Rex.

[End Spoiler Alert]

The Verdict

The Vanishing isn't an easy watch, and it certainly wasn't the kind of tape you'd casually pop in for a fun movie night back then. It’s a demanding, deeply unsettling film that probes uncomfortable questions about obsession, the nature of evil, and the horrifying randomness that can shatter ordinary lives. Its power lies in its quiet intensity, its refusal to offer easy answers, and the unforgettable performances, particularly Donnadieu's chillingly banal monster. It avoids typical thriller tropes, instead delivering a slow-burn psychological horror that lingers long after the credits roll.

Rating: 9/10

This rating reflects the film's near-perfect execution of its chilling premise, its masterful control of tone and suspense, the unforgettable antagonist, and its bravely uncompromising ending. It's a landmark of European thriller cinema, whose power hasn't diminished one bit since those grainy VHS days. What lingers most isn't just the shock, but the profound unease – the terrifying whisper that the Lemornes of the world might just be driving in the next lane, planning their own mundane horrors.