### That Quiet Enigma on the Foreign Film Shelf

Remember wandering the aisles of the video store, past the New Releases and the familiar genre sections, sometimes venturing into that slightly intimidating, often quieter corner labelled "Foreign Films"? Tucked away there, perhaps nestled between Fellini and Truffaut, you might have encountered a cover featuring Gérard Depardieu and Patrick Dewaere looking perplexed, flanking a beautifully melancholic Carole Laure. The title: Get Out Your Handkerchiefs (Préparez vos mouchoirs, 1978). Picking up that tape often felt like taking a chance, stepping outside the comfortable mainstream. And this particular film? It was a chance that delivered something utterly strange, unexpectedly tender, and undeniably provocative – a cinematic experience that lingers long after the credits roll, prompting questions that don't offer easy answers.

### A Husband's Bizarre Solution

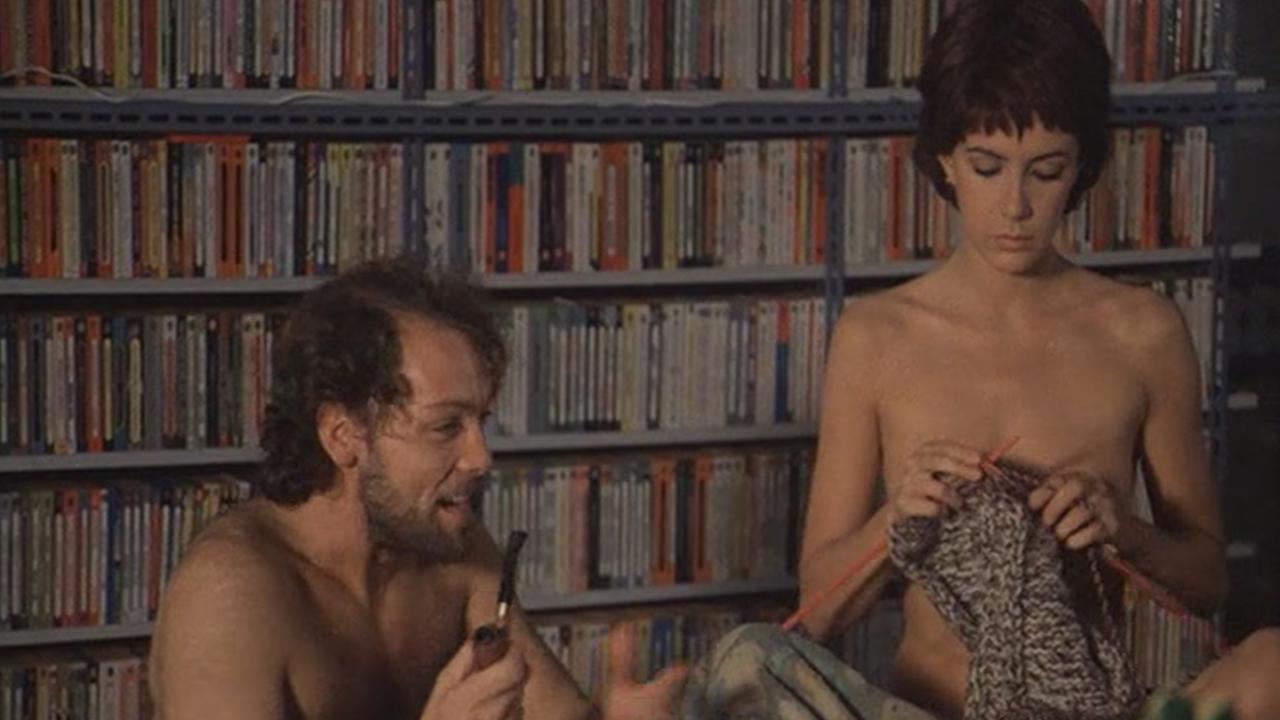

The premise, courtesy of writer-director Bertrand Blier, is audacious, almost breathtakingly so in its simple absurdity. Raoul (Gérard Depardieu) loves his wife, Solange (Carole Laure), deeply. The problem? Solange is perpetually unhappy, listless, knitting obsessively and sighing her way through life, seemingly immune to Raoul's boisterous attempts to cheer her up. His solution, born of a bizarre blend of desperation and misguided generosity, is to find her a lover. He selects Stéphane (Patrick Dewaere), a stranger encountered in a restaurant, believing this new man might ignite a spark that he cannot. What unfolds isn't a typical love triangle, but a peculiar, almost fraternal arrangement where Raoul and Stéphane become unlikely companions united by their shared, baffled affection for the enigmatic Solange and their complete inability to comprehend her malaise.

### The Blier Constellation

Anyone familiar with Blier's earlier sensation, Going Places (1974), which also starred the magnetic duo of Depardieu and Dewaere, will recognize the director's fingerprints here. There's that same focus on male camaraderie existing somewhat outside societal norms, the frank, often challenging depiction of sexuality, and the presence of female characters who remain fundamentally mysterious, perhaps unknowable, to the men orbiting them. Blier doesn't judge his characters; he observes their fumbling attempts at connection with a kind of deadpan amusement underscored by a deep empathy. The humor in Handkerchiefs isn't slapstick; it arises from the sheer peculiarity of the situation and the earnest, often clumsy ways Raoul and Stéphane navigate it. It’s a film that feels uniquely French in its willingness to explore unconventional relationships without neat moral resolutions.

### Performances of Truthful Bewilderment

The film rests heavily on its central trio, and their performances are remarkable. Gérard Depardieu, before becoming the international titan we know from films like Cyrano de Bergerac or Green Card, embodies Raoul with a touching blend of bluster and vulnerability. He’s a man of simple desires completely adrift in the face of complex emotion. Patrick Dewaere, whose tragic real-life story adds a layer of poignancy to his performances, is equally compelling as Stéphane. More intellectual and sensitive than Raoul, he’s nonetheless just as lost, drawn into this strange dynamic almost against his will. Their chemistry, a continuation of their partnership in Going Places, feels utterly authentic – two men bonded by a shared puzzle they can't solve.

But it's Carole Laure as Solange who provides the film's haunting center. Her performance is a masterclass in expressive passivity. Solange rarely articulates her feelings, her face a canvas of subtle discontent or fleeting, almost accidental, flickers of interest. She knits, she sighs, she eats, she sleeps, largely unresponsive to the men’s increasingly desperate attempts to make her happy. Is she depressed? Bored? Or simply operating on a different emotional frequency altogether? Laure makes her utterly captivating, ensuring Solange never feels like a mere object, but rather a profound mystery.

### Challenging Comfort Zones

Spoiler Alert! The film takes a turn that remains genuinely startling and, for many, deeply uncomfortable. Solange finally finds her spark, not with Stéphane, but with a highly intelligent, Mozart-obsessed 13-year-old boy (played with unsettling maturity by Riton Liebman) she encounters at a summer camp. The film presents this connection without condemnation, framing it as the one thing that finally awakens Solange from her stupor. It's a development that undoubtedly pushes boundaries, forcing viewers to confront uncomfortable questions about the nature of desire, connection, and happiness, especially when viewed through a modern lens. Blier isn't necessarily endorsing the relationship, but rather using it to highlight the complete failure of the adult men to understand or fulfill Solange's needs, and the unexpected places emotional resonance can be found.

### Oscar Surprise and Lingering Thoughts

Perhaps the most surprising piece of trivia surrounding Get Out Your Handkerchiefs is its reception: it won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1979. It feels almost impossible to imagine such a morally ambiguous and quirky film achieving that today, a testament perhaps to a different era of Oscar voting or the sheer power of its central performances and unique vision. The film’s budget was modest, but Blier crafts a world that feels lived-in, underscored beautifully by Georges Delerue's score, often incorporating the Mozart pieces beloved by Solange's young paramour, creating an ironic counterpoint to the emotional complexities on screen. It wasn’t a massive box office hit, but its critical acclaim, particularly the Oscar win, cemented its place in cinematic discourse. Finding this tape felt like uncovering a secret – a challenging, funny, and ultimately sad exploration of human connection that refused easy categorization.

---

Rating: 8/10

Justification: While the controversial elements require thoughtful consideration and may be off-putting for some, Get Out Your Handkerchiefs is a remarkably unique and well-crafted film. Blier's direction is assured, the central performances from Depardieu, Dewaere, and especially Laure are outstanding in their nuance, and the film's willingness to explore uncomfortable truths about relationships and happiness with dry wit and surprising tenderness is commendable. It avoids easy answers, provoking thought long after viewing, and stands as a prime example of challenging, character-driven cinema from the era – the kind of unexpected discovery that made browsing those video store shelves so rewarding.

Final Thought: What truly makes someone happy? This film doesn't pretend to know, but it memorably suggests the answer rarely lies where convention expects it to.