It arrived like a transmission from another frequency, didn't it? Nestled on the video store shelf, perhaps near the familiar comforts of Annie Hall (1977) or Manhattan (1979), the stark black-and-white cover of Woody Allen's Stardust Memories (1980) felt like a deliberate challenge. For many fans expecting another dose of neurotic wit and romantic entanglement, pushing this tape into the VCR must have felt like tuning into a different station altogether – one broadcasting directly from the anxieties and artistic frustrations of its creator, filtered through the stark, beautiful lens of European art cinema. It wasn't the easy laugh we might have sought, but something far more unsettling, and perhaps, ultimately, more resonant.

Ghosts in Monochrome

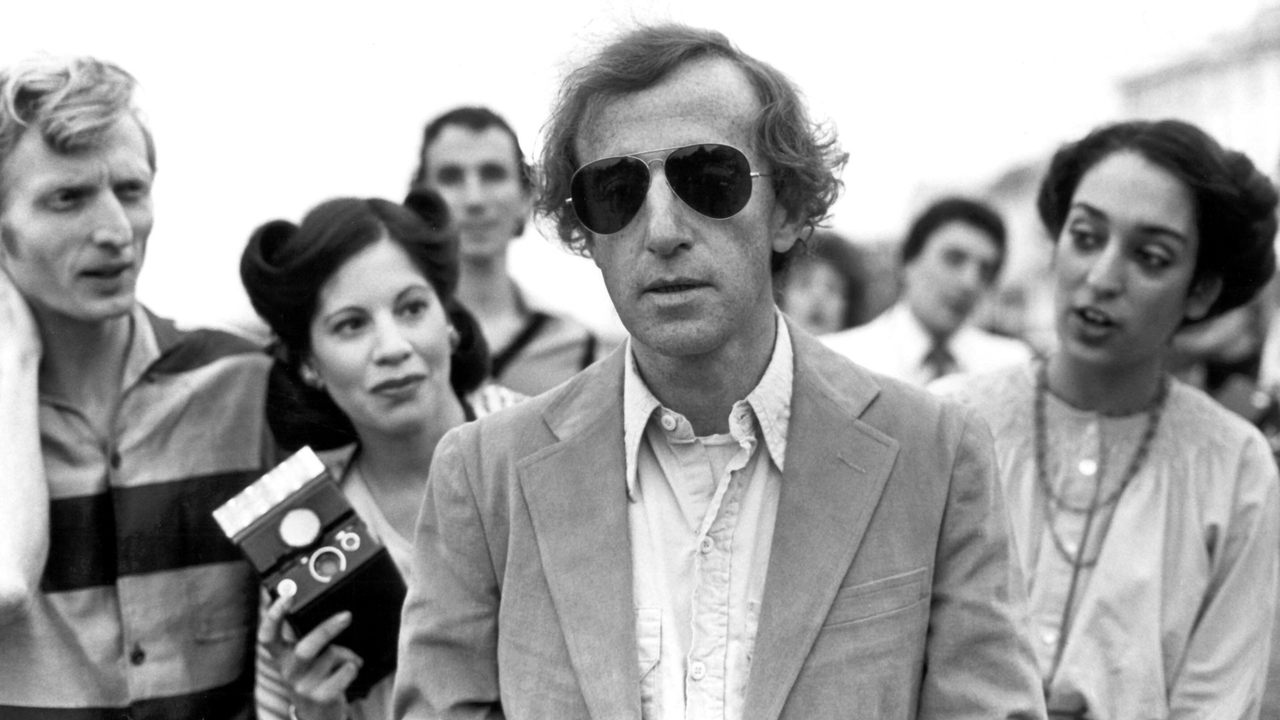

The most immediate jolt is the visual language. Teaming up again with the legendary cinematographer Gordon Willis (the eye behind The Godfather (1972) and Allen’s own recent triumphs), Allen ditches the warm hues of Manhattan for crisp, often hauntingly contrasted black and white. It’s a choice that immediately signals a shift in tone, aligning the film less with his contemporary comedies and more with the work of European masters, most notably Federico Fellini, whose 8 1/2 (1963) serves as an undeniable, almost overwhelming, spiritual blueprint. The opening sequence alone – featuring Allen’s character, filmmaker Sandy Bates, trapped on a train car filled with despairing faces, staring out at another train carrying vibrant, beautiful people – is pure Fellini-esque surrealism, a stark visual metaphor for artistic isolation and existential angst. Willis's compositions are breathtaking, turning hotel lobbies, screening rooms, and windswept beaches into landscapes of the mind, populated by figures both grotesque and achingly human.

"I Don't Want to Make Funny Movies Anymore"

At the heart of Stardust Memories is Sandy Bates (Woody Allen), a wildly successful filmmaker known for his comedies, who finds himself besieged by fans, critics, and his own existential dread during a retrospective film festival in his honor. He’s grappling with the perceived triviality of his popular work ("Should I stop making comedies and start dealing with the real problems of the world? Like suffering?") while simultaneously navigating the complex women in his life and the often-absurd demands of his fame. The accusations of autobiography flew thick and fast upon release, and it's easy to see why. Sandy’s predicament mirrored Allen’s own skyrocketing fame and artistic restlessness. Allen himself fiercely denied it was purely autobiographical, stating Sandy was a composite character exploring universal themes. Yet, the line feels intentionally blurred, forcing us to question the relationship between the artist, their art, and the persona the public consumes. Is Sandy Allen? Does it matter? The film seems to revel in this ambiguity.

Faces in the Crowd: Rampling, Harper, and the Grotesques

Surrounding Sandy are figures representing different facets of his life and desires. Charlotte Rampling, in a truly haunting performance, plays Dorrie – a former lover, beautiful, intelligent, but deeply troubled, embodying a kind of intense, perhaps destructive, passion. Rampling brings a fragile intensity to Dorrie; her scenes carry a weight that lingers long after they end. Contrasting her is Daisy, played by Jessica Harper (bringing a grounded warmth far removed from her iconic role in Dario Argento's Suspiria (1977)). Daisy represents a potentially more stable, grounded connection, yet even she isn't immune to the chaos surrounding Sandy. Adding another layer is French actress Marie-Christine Barrault as Isobel, Sandy's current partner, offering a semblance of mature stability that Sandy seems incapable of fully embracing.

Beyond these central figures, the film is populated by a memorable gallery of "grotesques" – the fans, critics, hangers-on, and industry types who clamor for Sandy's attention. Some were played by non-professional actors, adding to the film's unsettling realism and almost documentary feel in moments. They represent the often-unreasonable demands placed on artists, the yearning for connection (however clumsy), and perhaps, Allen suggests, the inherent absurdity of the human condition itself.

Echoes of Controversy and Craft

Stardust Memories was met with a decidedly mixed, often hostile, reaction upon its 1980 release. Critics and audiences felt Allen was being self-indulgent, arrogant, even contemptuous of his own audience. The film's perceived bleakness and departure from his comedic roots were jarring. Its $10 million budget yielded only slightly more at the box office, making it a commercial disappointment compared to his earlier hits. Yet, viewed decades later, perhaps removed from the immediate context of expectation, the film reveals itself as a brave, complex, and visually stunning piece of work.

It’s a film wrestling with big questions: What is the responsibility of an artist? Can comedy address suffering? Is lasting happiness attainable? Allen doesn't offer easy answers. The film’s structure, weaving flashbacks, dream sequences, and Sandy’s films-within-the-film, mirrors the fragmented nature of memory and thought. The jazz score, heavily featuring Louis Armstrong's rendition of "Stardust," adds another layer of melancholic beauty. Even the controversial ending, which pulls back the curtain on the film's own artifice, feels less like a gimmick now and more like a final, challenging statement about the nature of filmmaking and perception. Apparently, Allen later regretted the final shot, feeling it might have been too direct, but it certainly leaves an impression.

A Challenging Artifact from the Shelf

Stardust Memories isn't a comfort-food movie you pop in for easy laughs. It demands attention, provokes thought, and sometimes leaves you feeling as disoriented as Sandy Bates himself. Finding this tape back in the day might have felt like a gamble – would it be the Woody Allen you knew, or something entirely different? It was, resolutely, the latter. It’s a challenging, sometimes abrasive, but undeniably ambitious film. Its exploration of fame, art, and meaning feels surprisingly potent even now. Does it feel self-absorbed at times? Perhaps. But it's also deeply personal, visually arresting, and anchored by compelling performances, particularly from Rampling. It stands as a fascinating turning point in Allen's career, a moment where he explicitly confronted the image he'd created and dared to ask, "What else is there?"

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's artistic ambition, stunning cinematography, and thought-provoking themes, balanced against its intentionally challenging and sometimes alienating tone. It’s not Allen’s most accessible work, but it’s arguably one of his most visually striking and thematically complex, rewarding viewers willing to engage with its darker, more introspective frequency. It remains a stark reminder that sometimes, the most interesting journeys in cinema are the ones that don't offer easy answers or familiar comforts.