## The Uninvited Guest on Storm Island

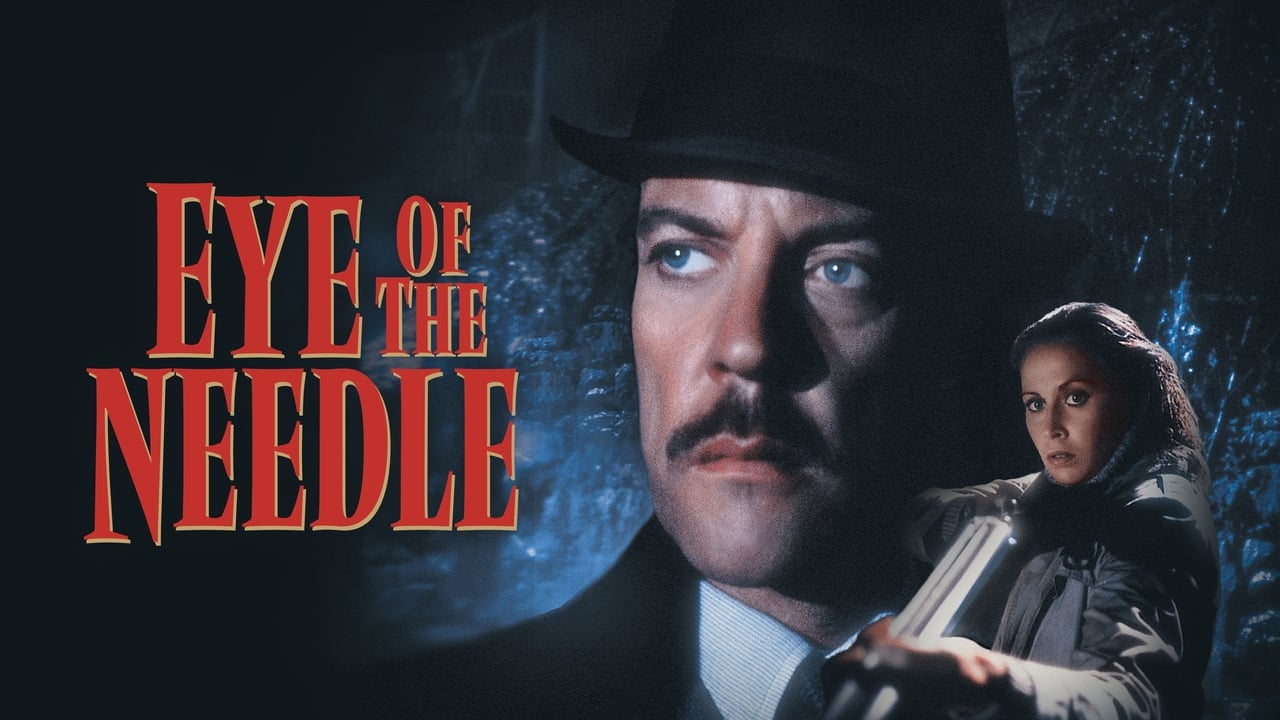

There’s a particular kind of chill that certain thrillers from the turn of the 80s managed, a coldness that wasn't just about plot twists, but about the uncomfortable truths they exposed beneath the surface of ordinary life. Eye of the Needle, released in 1981, embodies this perfectly. It begins as a seemingly straightforward spy yarn – a ruthless German agent, deep undercover in Britain, holding the key to D-Day – but morphs into something far more intimate and unsettling. What lingers long after the credits roll isn't just the espionage plot, but the devastating collision between the impersonal cruelty of war and the profound ache of human loneliness.

A Cold Professional Meets a Warm Isolation

The premise, drawn from Ken Follett's gripping bestseller, is elegantly simple yet fraught with tension. Heinrich Faber, codenamed 'Die Nadel' ('The Needle') for his preferred method of silencing opposition, is perhaps Germany's most effective spy embedded in England. Played with an unforgettable, reptilian stillness by Donald Sutherland, Faber is a phantom – meticulous, emotionless, utterly dedicated to his mission. When he uncovers crucial intelligence about the Allies' fictitious First United States Army Group, designed to mislead the Germans about the Normandy landings, getting this information back to the Fatherland becomes paramount. A frantic escape attempt leaves him shipwrecked, washing ashore on the remote, aptly named Storm Island off the coast of Scotland.

It's here the film truly finds its dark heart. Storm Island is inhabited by only a few souls, principal among them Lucy (Kate Nelligan), her embittered, wheelchair-bound former RAF pilot husband David (Christopher Cazenove), their young son, and the grizzled shepherd Tom (Ian Bannen). Lucy’s existence is one of quiet desperation, trapped in a passionless marriage on a desolate rock, yearning for connection. When the charming, seemingly harmless stranger Faber enters her life, the stage is set for a devastating intersection of duty, desire, and danger.

The Power of Performance

What elevates Eye of the Needle beyond a standard wartime thriller is the magnetic pull between Sutherland and Nelligan. Sutherland, fresh off his nuanced role in Ordinary People (1980), delivers a career-defining performance here. His Faber is terrifying not because he’s a monster, but because he’s so chillingly human in his unwavering commitment to his lethal purpose. There’s a watchfulness in his eyes, a calculated economy of movement, that speaks volumes. We believe utterly in his capacity for sudden, shocking violence, precisely because it erupts from such a controlled surface. It's said Sutherland remained intensely focused, almost method-like, during the Isle of Mull shoot, inhabiting Faber's isolated mindset – and it shows.

Kate Nelligan, in a performance that should be more widely celebrated, is his equal. She charts Lucy’s journey from aching loneliness and naive vulnerability to fierce maternal protectiveness and desperate courage with heartbreaking authenticity. Her initial attraction to Faber feels tragically believable, born not of foolishness but of a deep, starved need for warmth and attention in her bleak surroundings. The gradual dawning of realization in her eyes, the shift from fascination to fear, is masterfully done. You feel her isolation, her impossible choices, resonate deeply. Doesn't her predicament speak to the quiet battles fought far from any recognized front line?

Atmosphere as Character

Director Richard Marquand, in a fascinating move just before he took the helm of a galaxy far, far away for Return of the Jedi (1983), uses the stark, beautiful, and unforgiving landscape of the Isle of Mull to maximum effect. The wind howls, the sea crashes, and the isolation isn't just geographical; it's palpable, pressing in on the characters. Marquand, working from Stanley Mann's taut script, understands the power of suggestion and slow-burn suspense. He resists cheap scares, instead building tension through furtive glances, overheard whispers, and the growing sense that something is terribly wrong beneath the polite façade Faber presents. The film cost around $11.5 million, a respectable sum then, and much of it feels visible in the authentic, on-location grit.

Retro Fun Facts: Weaving the Details

- Shooting on Mull presented huge logistical challenges, from transporting equipment to dealing with the notoriously fickle Scottish weather, but Marquand insisted it was essential for the film's authentic feel of remoteness.

- Follett's novel was a massive international bestseller, and the film adaptation managed to capture its tense core, though some subplots were naturally streamlined. The book provides even more backstory for Faber, making his motivations clearer, if no less chilling.

- The film's tagline was stark and effective: "He was the deadliest agent of the war. She was the only woman who could stop him." It perfectly captured the intimate scale of this epic conflict.

- Look closely during Faber’s initial escape sequences in London – the attention to period detail is impressive for the time, really selling the wartime setting before the shift to the timeless isolation of the island.

Why It Holds Up on Tape (or Disc)

Watching Eye of the Needle today, perhaps digging out that slightly worn VHS copy procured from a dusty rental shelf years ago, feels like rediscovering a particularly potent piece of adult-oriented filmmaking. It lacks the frantic pacing of many modern thrillers, choosing instead to let the tension simmer, relying on character and atmosphere. There's a maturity to its approach, an exploration of complex emotions – love, betrayal, duty, survival – that feels refreshingly grounded. It's the kind of film that might have been overshadowed by flashier blockbusters back in the day, but its quality endures. I remember finding it nestled between louder action flicks at the local video store, a surprisingly intense and thoughtful experience.

Does it feel a little 'old-fashioned' now? Perhaps in its pacing compared to today's standards. But its core strengths – the powerhouse performances, the suffocating atmosphere, the morally complex narrative – remain undiminished. It asks uncomfortable questions about the nature of evil and the desperate measures ordinary people will take when pushed to the brink.

Rating: 8.5/10

This score is earned through the sheer force of Donald Sutherland's chillingly precise performance and Kate Nelligan's deeply affecting portrayal of vulnerability turned strength. Add the masterful build-up of suspense by director Richard Marquand, the evocative use of location, and a script that smartly translates Ken Follett's bestseller, and you have a standout wartime thriller. It might move at a more deliberate pace than some expect, but the tension is palpable and the emotional impact profound.

Eye of the Needle remains a potent reminder that the most dangerous conflicts aren't always fought on battlefields, but sometimes across a kitchen table, fueled by secrets and sealed by desperation. A truly gripping slice of 80s cinema that deserves its place on any discerning retro shelf.