Few films arrived smelling quite so strongly of chum and potential litigation as 1981’s The Last Shark (also known, perhaps more honestly, as L'ultimo squalo). This wasn't just a monster movie; it was cinematic audacity incarnate, a film that swam so closely in the wake of a certain blockbuster behemoth that the legal fins started circling almost immediately. Watching it again, decades later on a slightly fuzzy transfer, that sense of almost reckless imitation hangs heavy in the salt-laced air, creating an atmosphere thicker than murky harbour water.

Borrowed Waters, Familiar Fears

Let's not beat around the coral reef: the plot echoes Spielberg's 1975 masterpiece, Jaws, with an almost defiant lack of subtlety. We have a coastal town, Port Harbor, gearing up for its annual Windsurfing Regatta. We have mysterious disappearances and mangled remains washing ashore. We have a politician figure, the Mayor (Joshua Sinclair), desperate to keep the beaches open for tourism dollars, denying the growing threat. Sound familiar? Our Brody equivalent is Peter Benton (James Franciscus), a horror novelist (!), who tries to raise the alarm, while the Quint-esque grizzled sea dog role falls to Ron Hamer (Vic Morrow), a local shark hunter with a personal vendetta. The beast itself? A colossal, inexplicably aggressive Great White shark with a seemingly supernatural ability to hold grudges and destroy piers with explosive force. The similarities are undeniable, blatant even, forming the very bedrock of the film's troubled legacy.

Castellari's Carnage

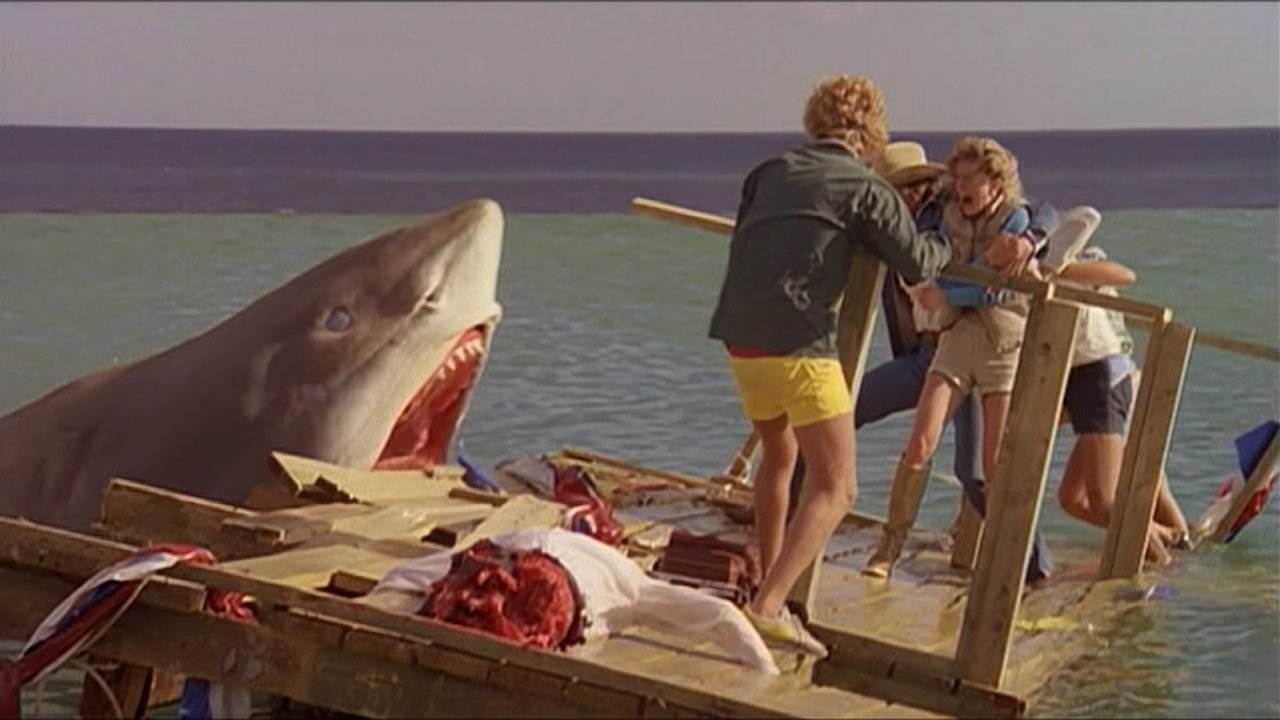

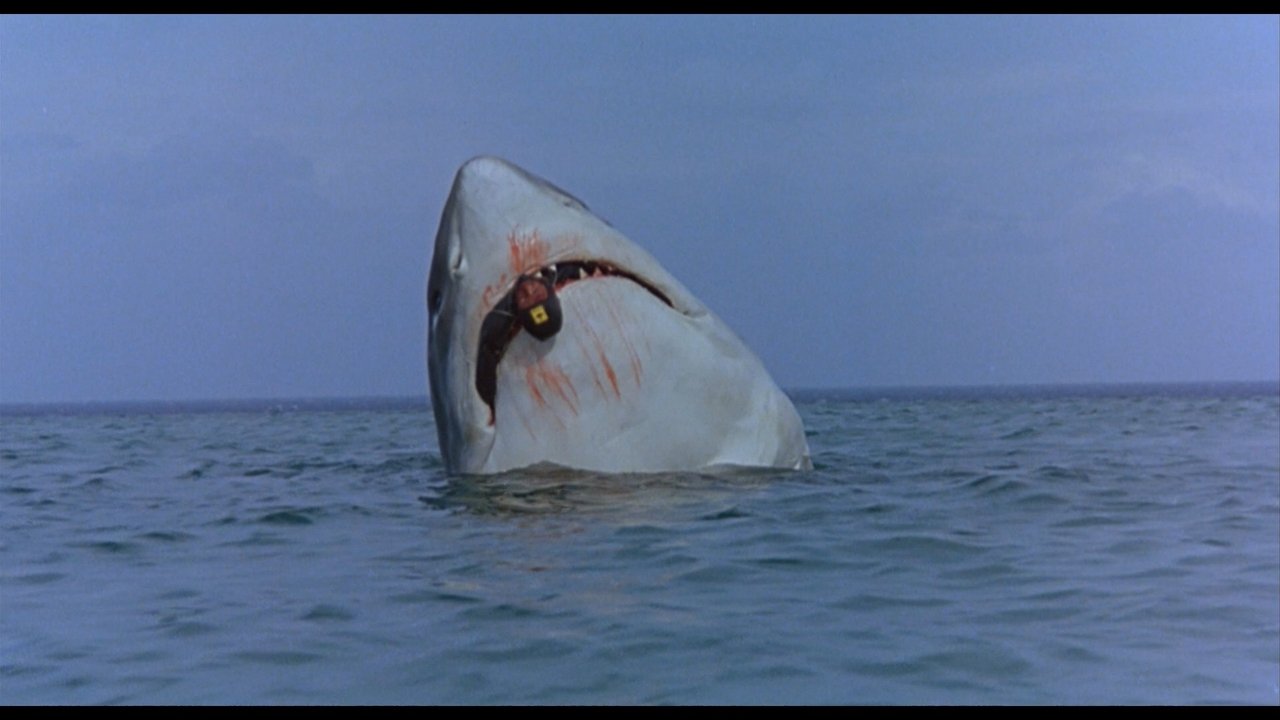

Yet, dismissing it solely as a cheap knock-off feels... incomplete. Behind the lens was Italian action maestro Enzo G. Castellari, known for gritty poliziotteschi like The Big Racket (1976) and later, the original The Inglorious Bastards (1978). Castellari brings a certain rough-and-tumble energy to the proceedings. While lacking Spielberg's patient, Hitchcockian build-up, Castellari dives headfirst into the carnage. The attacks are often surprisingly graphic for the time, leaning into the exploitation aesthetic. Limbs are severed, boats are splintered, and there's a palpable sense of frantic desperation in the underwater sequences, even when the limitations of the effects are apparent. Castellari wasn't aiming for suspense; he was orchestrating aquatic chaos, and in certain moments, he delivers a visceral jolt that, back in the day, could genuinely make you jump.

The Beast That Wouldn't Behave

Of course, the shark itself is central. The practical effects are... well, they're something. The full-scale mechanical shark reportedly suffered numerous malfunctions, mirroring the infamous issues with "Bruce" on the Jaws set, though likely with a far smaller budget for repairs. Legend has it the main prop even sank at one point during filming off the coast of Malta, requiring retrieval. The miniature work, particularly the shark ramming boats or munching on a helicopter (yes, really), possesses a certain charmingly destructive quality that feels distinctly of the era. Does it look real? Not particularly, especially by today's standards. But doesn't that slightly stiff, unblinking menace hold a certain uncanny dread all its own, a hallmark of 80s creature features? My well-worn tape, probably a third-generation copy procured through hushed trades back in the day, seemed to amplify the grainy menace of the underwater shots.

Anchored Performances

James Franciscus (Beneath the Planet of the Apes) brings a weary earnestness to Benton, the man nobody believes until it’s nearly too late. He grounds the film as much as possible amidst the escalating absurdity. But it's Vic Morrow (Combat!, The Bad News Bears), in one of his final roles before his tragic death during the filming of Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983), who truly commands the screen. His Ron Hamer is less nuanced than Robert Shaw's Quint, more of a straightforward, grimly determined Ahab figure, but Morrow imbues him with a weathered intensity that makes you believe he could actually wrestle this sea demon. His presence adds a layer of gravitas the film desperately needs.

Harpooned by Hollywood

The most fascinating part of The Last Shark's story happened off-screen. Universal Pictures, understandably protective of their Jaws franchise, swiftly filed a lawsuit citing copyright infringement. Despite The Last Shark pulling in a reported $18 million in its first month of US release (a significant sum on its estimated $2 million budget – roughly $6.5 million today yielding $58 million adjusted), Universal won an injunction. The film was pulled from American theaters and largely vanished from legitimate circulation in the States for decades, becoming a piece of semi-forbidden VHS contraband, whispered about by horror fans. Did you ever manage to snag a bootleg copy back then, feeling like you were watching something illicit? That very unavailability added to its mystique.

---

Final Verdict:

The Last Shark is undeniably derivative, occasionally clumsy, and features effects that haven't aged gracefully. Yet, it possesses a certain gonzo energy, courtesy of Enzo G. Castellari, and benefits immensely from the committed performances of Franciscus and especially Morrow. It’s a fascinating artifact of early 80s exploitation cinema and the "Jawsploitation" subgenre it so boldly embodies. The behind-the-scenes drama surrounding its release arguably eclipses the on-screen narrative.

Rating: 4/10

Justification: The score reflects the film's overwhelming derivativeness and technical shortcomings. Points are awarded for Castellari's energetic direction in action sequences, Morrow's strong presence, and the sheer, unadulterated B-movie audacity that makes it a memorable, if flawed, piece of aquatic horror history. It fails as a truly scary or original film, but succeeds as a notorious cult curiosity.

It remains a prime example of cinematic shark jumping, a film torpedoed by its own imitation, yet kept afloat in the murky depths of VHS fandom precisely because of its infamous reputation.