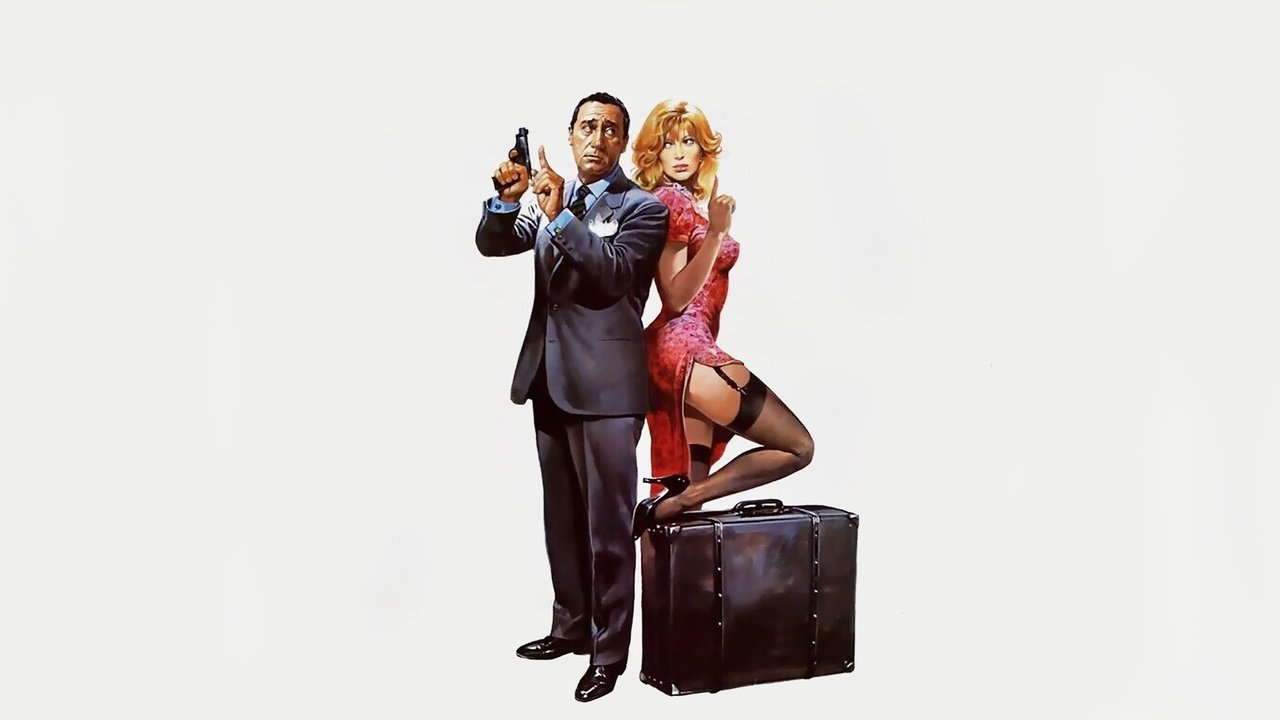

It begins with an accident, a mundane slip that spirals into something far more profound. Imagine finding a hidden cache of VHS tapes, not filled with recorded broadcasts or cherished home movies shared openly, but secret recordings of your life, meticulously documented by your own spouse for years. This unsettling premise sits at the heart of Alberto Sordi's 1982 film Io so che tu sai che io so (or, I Know That You Know That I Know), a peculiar and often poignant blend of comedy and drama that uses the nascent home video technology of the era not for laughs, but as a scalpel to dissect a modern marriage.

Unveiling the Unseen

Sordi, a true giant of Italian cinema, directs and stars as Fabio Bonetti, a seemingly content, middle-aged bank executive coasting through life with a degree of comfortable obliviousness. He believes he has a handle on his world – his job, his wife Livia (Monica Vitti, another Italian screen legend), his teenage daughter Veronica (Isabella De Bernardi). It’s a façade shattered when, investigating a suspected affair involving his daughter, Fabio stumbles upon Livia's secret video archive. Hours upon hours of tape reveal not just infidelity (though not his own, initially), but the quiet dissatisfactions, the hidden anxieties, and the sheer banality of their existence, all captured through Livia’s unblinking lens.

What starts almost like a farce – the bumbling husband discovering secrets – gradually darkens. The tapes become a relentless mirror, forcing Fabio to confront truths he’d rather ignore: his own health neglect, his wife's deep-seated loneliness, the growing distance within the family. The humour, typical of the Commedia all'italiana style Sordi mastered, becomes increasingly laced with melancholy. It’s the laughter that catches in your throat, recognizing the painful absurdity of lives lived side-by-side yet worlds apart.

A Masterclass in Nuance

The film rests heavily on the shoulders of its two leads. Sordi delivers a performance of remarkable vulnerability. His Fabio transforms from a somewhat complacent, even buffoonish figure into a man stripped bare, grappling with confusion, anger, and ultimately, a crushing sense of existential doubt. We see the weight of realization settle on him, the way his posture changes, his familiar mannerisms dissolving into uncertainty. It’s a performance that reminds us why Sordi wasn't just a comedian, but a profound chronicler of the Italian psyche.

Opposite him, Monica Vitti is equally compelling. Livia isn't presented as a simple villain or voyeur. Her motivations are complex, born perhaps from a desperate need to understand, to connect, or maybe just to feel something real in a life that feels increasingly artificial. Vitti imbues Livia with a quiet sadness, a sense of resignation mixed with a strange form of agency through her secret filming. Her face, often captured in reaction shots as Fabio watches the tapes, speaks volumes about the unspoken history between them. Their dynamic, built over previous collaborations like Polvere di stelle (1973), feels lived-in and authentic, making the eventual breakdown all the more resonant.

Technology as Truth Serum

Released in 1982, the film taps directly into the anxieties and possibilities surrounding the burgeoning home video market. Remember those hefty VHS camcorders, the ones that practically required a shoulder strap? Here, that technology, promising family memories and shared moments, becomes an instrument of unintentional exposure. It predates the ubiquitous surveillance of the internet age and the curated performance of reality TV, yet it presciently explores the idea of the unblinking eye within the home. What does it mean when our private lives are recorded, not by an oppressive state, but by the person sleeping next to us? What truths emerge when the performance of everyday life is stripped away?

Longtime Sordi collaborator Rodolfo Sonego, along with Augusto Caminito, co-wrote the screenplay, and their understanding of Sordi's screen persona and thematic preoccupations is evident. The film probes the comfortable hypocrisies of bourgeois life, a recurring theme in Sordi's work, but with a distinctly modern, tech-inflected twist. The setting, Rome in the early 80s, feels authentic – the fashion, the apartments, the societal backdrop contributing to the film’s specific flavour.

Beneath the Surface

I Know That You Know That I Know isn't a perfect film. Its pacing occasionally meanders, and the blend of comedy and drama can sometimes feel uneven. Yet, its central premise is undeniably powerful and thought-provoking. It sticks with you, this idea of lives secretly observed, of truths hidden in plain sight until technology forces a confrontation. It feels like a distinctly Italian take on marital ennui, filtered through Sordi's unique sensibility – cynical yet sympathetic, critical but ultimately humane.

Watching it today, perhaps on a worn-out VHS copy dug out from the back of a shelf, carries its own layer of resonance. The bulky technology seems quaint, yet the questions the film raises about intimacy, perception, and the masks we wear feel startlingly contemporary. Doesn't the curated perfection of social media echo, in a way, Livia’s selective recording, albeit with a different intent?

Rating: 7/10

This rating reflects the film's compelling central concept, the superb performances from Sordi and Vitti, and its insightful, if sometimes melancholic, exploration of marriage and hidden truths. It earns points for its unique place as an early exploration of domestic surveillance via home video. However, its pacing and tonal shifts might not resonate with everyone, keeping it from higher marks. It’s a thoughtful, slightly bittersweet piece of 80s Italian cinema that lingers more than its initial comedic setup might suggest.

Ultimately, I Know That You Know That I Know leaves us pondering the uncomfortable space between what we project and who we really are, and the unexpected ways truth can find its way to the surface, even through the grainy images on a forgotten VHS tape.