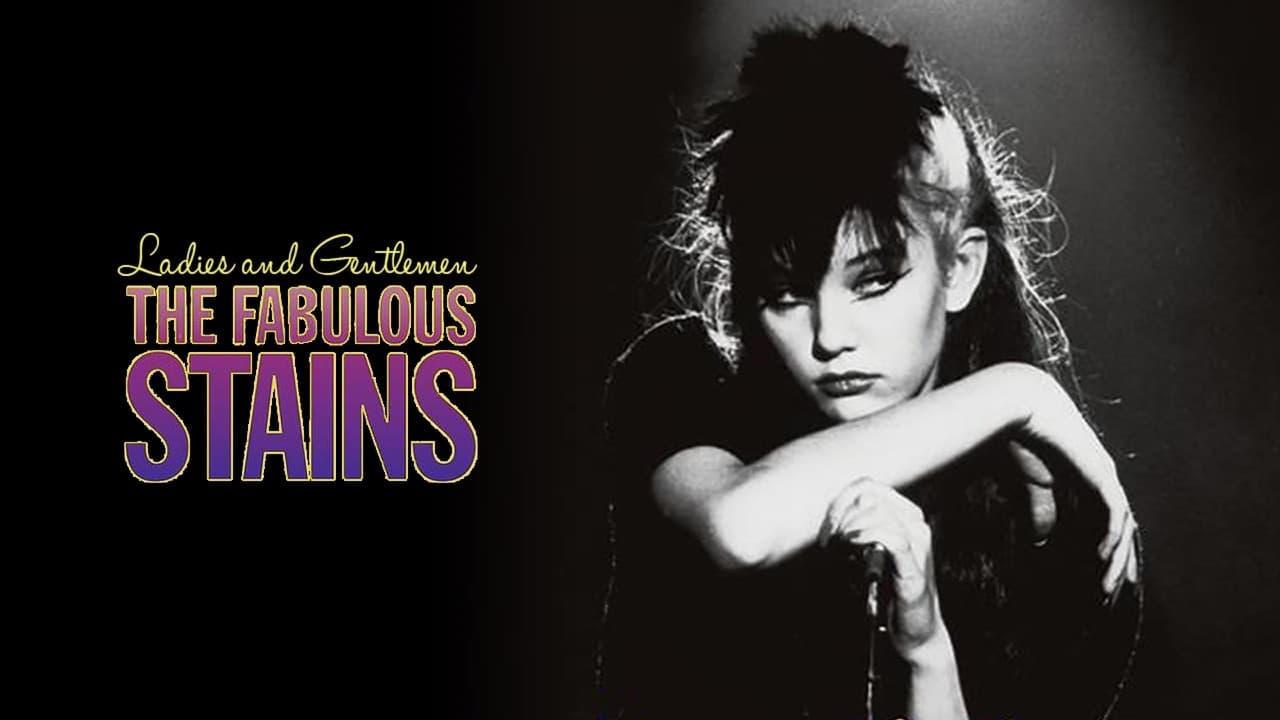

Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains

It feels less like a movie you watched and more like a transmission you intercepted, doesn't it? A fuzzy, static-laced broadcast from a world both instantly recognizable and strangely alien. Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains (1982) wasn't something you casually picked up at Blockbuster; it was a whisper, a rumour, a tape passed hand-to-hand or maybe caught bleary-eyed on some late-night cable channel years after it was supposed to have vanished. And perhaps that elusive, almost accidental journey into our VCRs is precisely why it still resonates with such raw, unvarnished power.

A Ghost in the Machine

This film's very existence feels like a minor miracle, or maybe just a fascinating accident. Directed by music industry veteran Lou Adler (known more for producing Carole King and The Mamas & the Papas than punk manifestos) and penned by Nancy Dowd (who won an Oscar for Coming Home (1978) but famously took her name off this picture, using the pseudonym "Rob Morton" after disputes), Stains had a notoriously troubled path. Filmed around 1980, it barely saw the light of day, plagued by poor test screenings and studio cold feet. Shelved for years, its legend grew primarily through those scarce late-night airings and bootleg VHS tapes – a perfect mirror, perhaps, to the band's own fleeting, manufactured fame within the narrative. You couldn't just find this movie; you had to discover it, which made the connection feel intensely personal, like uncovering a secret history.

"We Don't Put Out"

Set against the appropriately bleak backdrop of decaying, post-industrial Pennsylvania, the film follows Corinne Burns (Diane Lane), a teenage orphan simmering with unfocused rage after her mother's death. Witnessing the tired theatrics of washed-up metal act The Metal Corpses and the nihilistic swagger of British punk band The Looters (fronted by a sneering Ray Winstone, and featuring actual punk royalty Paul Simonon of The Clash, plus Steve Jones and Paul Cook from the Sex Pistols), Corinne sees not inspiration, but opportunity. She quickly forms The Stains with her sister (a young Marin Kanter) and cousin (an equally young Laura Dern), despite having virtually zero musical talent.

Their genius, if you can call it that, lies in provocation. Corinne, adopting a striking skunk-stripe hairstyle and see-through blouse over stolen lingerie, becomes an instant icon of defiance for the disaffected girls in the audience. Their infamous motto, "We don't put out," becomes less a statement about sex and more a declaration of radical non-participation, a rejection of everything expected of them. It’s pure, unfiltered teenage fury packaged as performance art, and it catches fire precisely because it’s so raw and confrontational. Does it matter that they can barely play? The film suggests, perhaps chillingly, that it doesn't.

The Glare of Diane Lane

What truly elevates Stains beyond a mere punk curiosity is the absolutely searing performance by Diane Lane. Only around 15 or 16 during filming, she embodies Corinne with a magnetic intensity that's almost unnerving. It’s not a polished performance; it’s volatile, brittle, radiating a palpable sense of anger and vulnerability beneath the tough exterior. Her defiant glare, the way she channels adolescent alienation into a weapon – it’s unforgettable. You watch her navigate the predatory landscape of the music industry, manipulate the media (represented by David Clennon's opportunistic local news reporter), and whip up a frenzy among young female fans, and you see both a desperate kid trying to survive and a frighteningly astute commentator on the mechanisms of fame. It's a performance that feels astonishingly authentic, capturing that specific brand of teenage certainty built on shaky foundations.

The presence of actual musicians like Simonon, Jones, and Cook adds another layer of gritty realism. The Looters feel less like actors playing a band and more like, well, a band – cynical, slightly bored, but capable of generating genuine energy. Ray Winstone, even then, had that coiled intensity that made him perfect as the band's volatile frontman.

More Than Just Noise

Beyond the punk aesthetics and the compelling central performance, Stains digs into themes that feel remarkably prescient. Dowd's script (even disowned) is a sharp critique of media manipulation, the commodification of rebellion, and the way female anger is often packaged and sold back to us. How quickly does Corinne's genuine rage become a marketable gimmick? How easily are her followers swayed by the next trend? The film doesn't offer easy answers, presenting the Stains' rise and inevitable fall with a stark, almost cynical clarity. It anticipated the discussions around "selling out," the manufacturing of counter-culture, and the specific pressures faced by women in creative industries long before riot grrrl made them explicit. Remember how startlingly direct that felt back then, cutting through the usual rock movie clichés?

Sure, the film has its rough edges. The pacing can feel uneven, a likely result of its troubled post-production. Some plot points feel underdeveloped. But these imperfections almost enhance its cult appeal, making it feel less like a slick Hollywood product and more like a found object, a grainy snapshot of a specific moment of cultural disillusionment. It’s a film that feels made, not manufactured, capturing lightning in a bottle – even if the bottle got dropped and glued back together a few times.

Rating: 8/10

Why an 8? Because despite its flaws and troubled history, Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains remains a vital, potent piece of filmmaking. Diane Lane's iconic performance is electrifying, the critique of media and fame still bites hard, and its raw, punk energy feels utterly authentic. It captures the anger, confusion, and desperate yearning for identity of its era with startling honesty. Its journey from obscurity to beloved cult classic via the underground railroad of VHS and late-night TV only adds to its mystique.

It’s a film that doesn't just show rebellion; it questions its very nature, leaving you wondering about the line between genuine expression and calculated performance – a question perhaps even more relevant today than it was back in the smoky haze of the early 80s.