Here we go, digging into a different kind of gem from the VHS shelves today. Not the explosive action or high-concept sci-fi, but something quieter, starker, yet deeply resonant about the very act of creation itself.

### Waiting for Godot, or Maybe Just the Producer

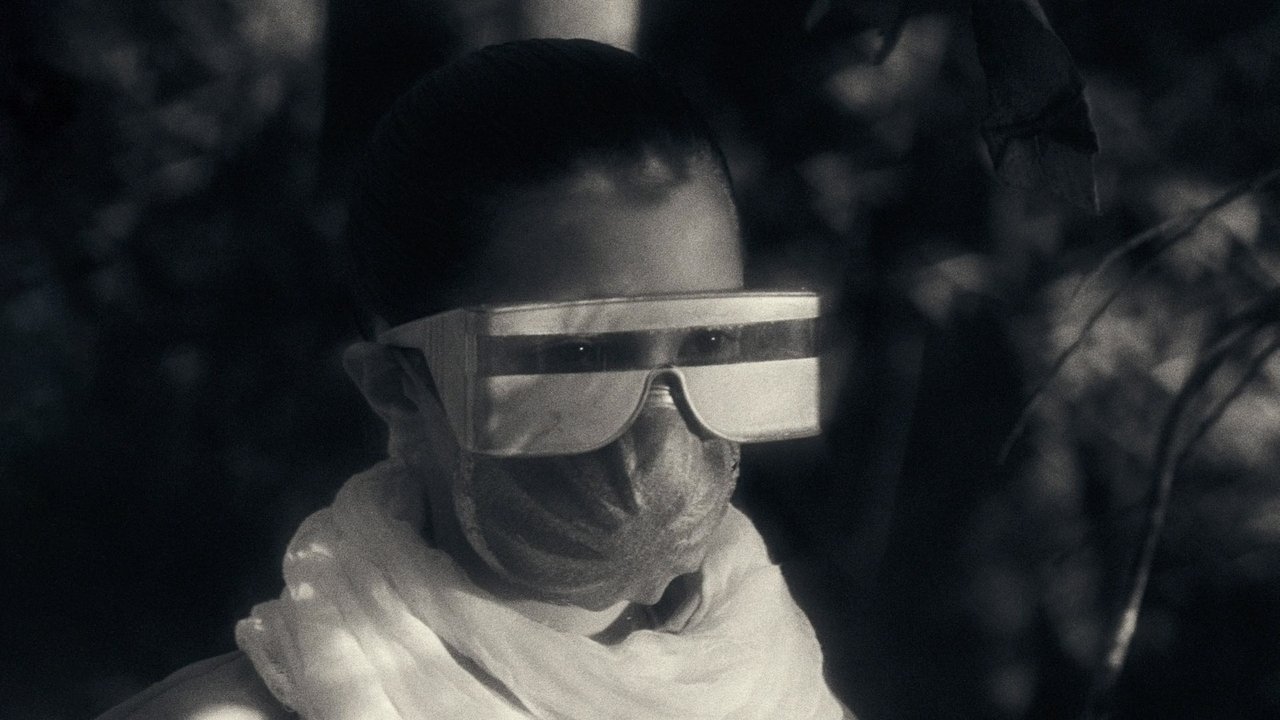

What happens when the story stops? Not just within the film being watched, but within the film being made? Wim Wenders’ 1982 mood piece, The State of Things (Original title: Der Stand der Dinge), plunges us directly into that creative limbo. Shot in stark, beautiful black and white, it opens on a film crew stranded in a desolate coastal hotel in Portugal. They're making a low-budget sci-fi B-movie, a remake called 'The Survivors', but the money has dried up, the producer is missing, and the film stock is running low. All they can do is wait, wander, talk, and reflect, trapped in a kind of existential holding pattern.

This premise alone is intriguing, but the real magic – and the source of the film’s palpable atmosphere of weary authenticity – lies in its origin story. This wasn't just a concept Wenders dreamed up; it was born directly from his own profoundly frustrating experience directing Hammett (1982) for Francis Ford Coppola's Zoetrope Studios. Beset by constant delays, rewrites, and creative interference on that troubled production, Wenders took a break, grabbed some leftover black-and-white film stock from Hammett, flew his core crew to Portugal, and essentially channeled his own anxieties and paralysis into The State of Things. Knowing this backstory transforms the viewing experience; the crew's boredom, philosophical musings, and simmering frustration feel utterly genuine because, in many ways, they were. Wenders wasn't just directing a film about being stuck; he was stuck.

### Portraits of Creative Purgatory

The performances here are key to the film's quiet power. Patrick Bauchau, who Wenders fans might recognise from later collaborations, plays Friedrich Munro, the director of the film-within-a-film. He embodies a thoughtful weariness, a man trying to hold onto his artistic vision while navigating the crushing practicalities (or lack thereof) of financing. His anxieties feel incredibly real, perhaps mirroring Wenders' own state of mind.

Then there's Allen Garfield (sometimes credited as Allen Goorwitz), playing the perpetually absent, eventually confronted producer, Gordon. Garfield, a familiar face from films like The Conversation (1974) and Nashville (1975), brings a specific kind of nervous energy to the role – a blend of salesman charm, evasiveness, and perhaps genuine fear. His eventual appearance shifts the film's dynamic, introducing a different kind of tension.

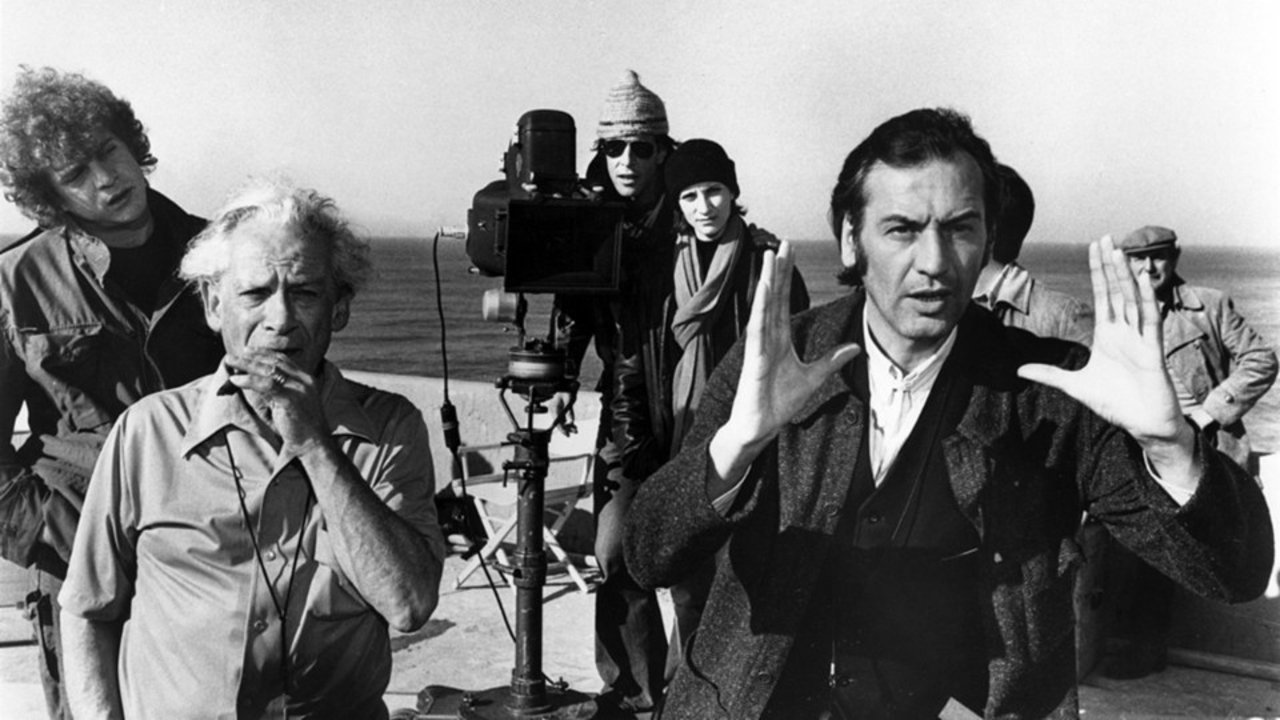

And for cinephiles, the presence of legendary director Samuel Fuller (Pickup on South Street, The Big Red One), playing Joe Corby, the veteran cinematographer of the stranded crew, is a particular treat. Fuller, cigar often clenched in his teeth, delivers his lines with characteristic gravelly authority. There's a poignant meta-layer here: Fuller, a maverick filmmaker known for his lean, tough style, portraying a craftsman within a film made by another director grappling with the industry's pressures. His very presence feels like a commentary on survival and integrity in filmmaking.

### More Than Just Waiting

While much of the film involves conversations, quiet observation, and capturing the desolate beauty of the Portuguese coast (cinematography by the great Henri Alekan, who would later shoot Wenders' Wings of Desire), it's far from static. It’s a meditation on the clash between European art cinema sensibilities and the demands of the American market (personified by Garfield's producer). It explores the fundamental question: why tell stories at all, especially when faced with silence and uncertainty?

The film famously uses leftover 35mm film stock, lending it not just its B&W aesthetic but also a tangible sense of resourcefulness born from constraint. This wasn't just an artistic choice; it was partly a practical necessity, mirroring the crew's situation in the narrative. Co-written with Robert Kramer, another independent filmmaker known for his politically charged work, the script feels less plotted and more observed, capturing the rhythm of waiting and the bursts of philosophical inquiry that surface in moments of inactivity. It’s a film about process, or rather, the suspension of process.

Its impact was significant, if quieter than a blockbuster splash. The State of Things won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1982, a major validation of Wenders' impromptu, deeply personal project. It stands as a fascinating companion piece to Hammett, offering an almost documentary-like glimpse into the emotional and creative fallout of that production, filtered through a fictional lens.

### The Verdict

The State of Things isn't your typical Friday night VHS rental fare from the 80s. It demands patience and a willingness to sink into its contemplative mood. There are no car chases, no explosions, just the quiet drama of creative souls adrift. But for those interested in the art of filmmaking itself, or in Wenders' unique brand of philosophical road-movie sensibility (even if the 'road' here is mostly stationary), it's a deeply rewarding experience. It captures a specific kind of anxiety – the fear that the resources, or perhaps even the reasons, for telling stories might simply vanish.

Rating: 8/10

Justification: This score reflects the film's artistic integrity, its fascinating meta-narrative born from real-life production struggles, the strength of its atmospheric black-and-white cinematography, and the authentic performances, particularly Bauchau's weary director and Fuller's iconic presence. It’s a unique and thoughtful piece of 80s cinema, capturing a specific mood of creative uncertainty with profound honesty. While its deliberate pace might not appeal to all, its depth and unique origin make it a standout work.

Final Thought: It’s a film that stays with you, less for its plot and more for the lingering feeling of being caught between frames, waiting for the next reel to arrive. What does it mean to keep filming when the money runs out and the narrative falters? Wenders doesn't offer easy answers, but the question itself resonates long after the static fills the screen.