It begins not with a narrative hook, but with a sense of quiet searching. A filmmaker, already established and revered, embarks on a journey not just across the globe, but seemingly across time itself. This is Wim Wenders in 1983, arriving in Japan with a specific ghost in mind: the spirit of the legendary director Yasujirō Ozu, whose quietly profound films depicted a Japan that, even then, felt like it was slipping away. Tokyo-Ga (1985) isn't a traditional documentary; it's a filmed diary, a meditative essay, a sometimes melancholic, sometimes bewildered encounter with a metropolis hurtling into the future while clinging to fragments of its past.

### A City of Contradictions

Wenders, camera often handheld, voiceover occasionally guiding us with his thoughtful, almost hesitant observations, wanders through Tokyo. He seems less interested in crafting a definitive portrait and more in capturing impressions, moments, textures. We see the hypnotically frantic energy of pachinko parlors, the almost surreal dedication of businessmen practicing their golf swings on rooftop driving ranges, the meticulous artistry of fake food models destined for restaurant windows. These aren't exposé moments; they are fragments of a city that fascinates and perhaps slightly unnerves him. He’s looking for Ozu’s Tokyo – the quiet domesticity, the gentle rhythms, the low-angle shots capturing life unfolding within tatami-matted rooms. Instead, he finds a city pulsating with neon, Western rock music blaring from unexpected corners, and a pervasive sense of constant motion. Does the search feel futile at times? Absolutely, and Wenders doesn't shy away from that uncertainty.

### Seeking Ozu's Echoes

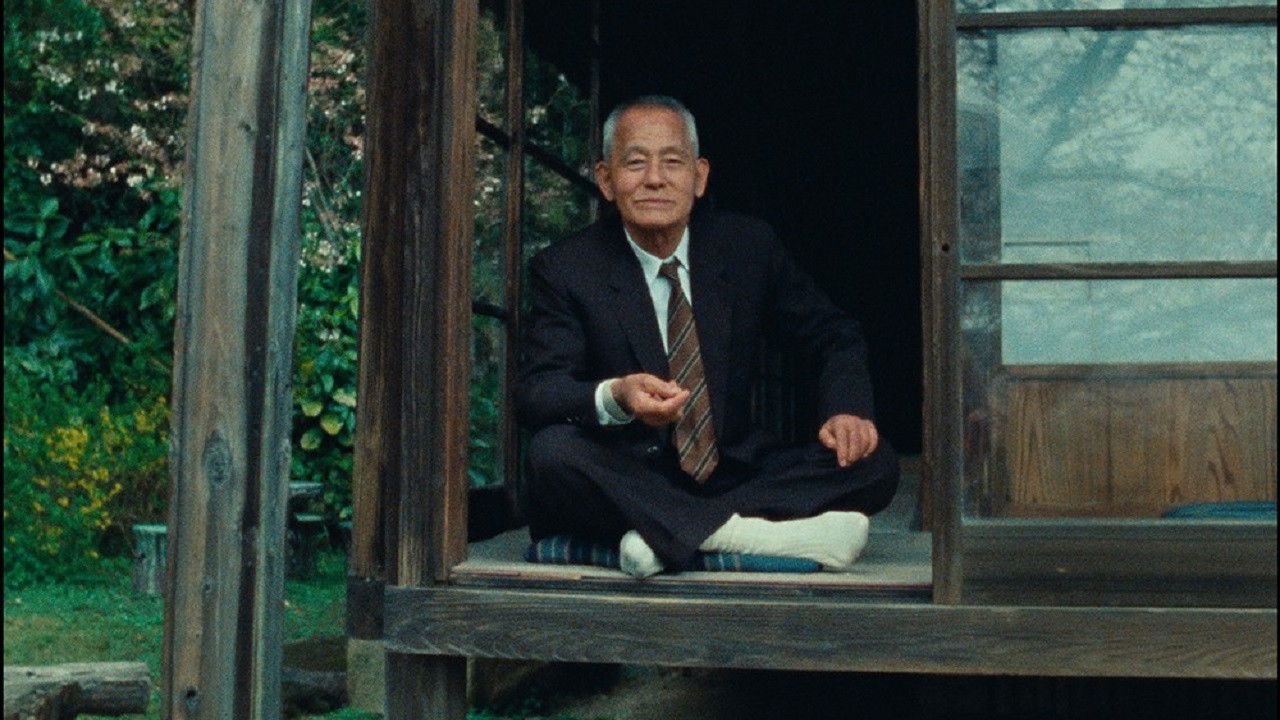

The quest for Ozu anchors the film. Wenders seeks out two key figures from the master's cinematic family: actor Chishū Ryū, the quintessential Ozu father figure, and cinematographer Yūharu Atsuta. These encounters are the heart of Tokyo-Ga. The conversation with Ryū is particularly poignant. Seeing this familiar, gentle face, now aged, discussing his work with Ozu feels like bridging a tangible link to a bygone era of filmmaking. There's a quiet dignity, a shared respect between the two men, that transcends language barriers. Wenders films Ryū much like Ozu might have, allowing his presence to fill the frame with quiet authority. Similarly, Atsuta offers insights into Ozu's famously meticulous methods – the precise camera placement, the deliberate pacing – reinforcing the sense of a lost cinematic language. Wenders even visits Ozu's grave, a simple, reflective moment that underscores the personal nature of his journey.

### Chance Encounters and Philosophical Musings

It’s not all Ozu, though. Tokyo-Ga captures Wenders’ own sensibility filtering the experience. He documents the painstaking process of crafting wax food models, finding artistry in the mundane. He muses on the ubiquitous presence of screens, a theme that resonates even more strongly today. And then, almost randomly, another giant of cinema appears: Werner Herzog. Their impromptu conversation atop the Tokyo Tower, discussing the challenges and absurdities of filmmaking while overlooking the sprawling cityscape, is a delightful, slightly surreal highlight. It’s a collision of two distinct European filmmaking perspectives, finding common ground amidst the alien landscape. This wasn't planned; Herzog just happened to be in Tokyo, a testament to the serendipitous nature of Wenders' journey. Hearing Herzog declare the city lacks "genuine images" while surrounded by its overwhelming visual stimuli provides a fascinating counterpoint to Wenders' more receptive gaze.

### A Time Capsule with Lingering Questions

Watching Tokyo-Ga today, perhaps on a worn VHS tape pulled from the back of a shelf, feels doubly nostalgic. It's a portal not just to Ozu's time, but to the mid-1980s itself – a specific moment when Japan felt like the future, yet Wenders was seeking its soul in the past. The technology, the fashion, the very atmosphere he captures feels distinctly of that era. It wasn’t a massive hit upon release; this was always more of an art-house piece, the kind of film you might discover tucked away in the "Foreign Films" section of a particularly well-stocked video store, rented more out of curiosity or admiration for Wenders (coming off Paris, Texas and heading towards Wings of Desire) than mainstream buzz.

The film doesn't offer easy answers. Did Wenders find Ozu's ghost? Perhaps not in the way he expected. But he found something else: a complex, rapidly changing culture grappling with its identity, reflected through the lens of a filmmaker deeply respectful of cinema's past. It raises questions about authenticity, progress, and the very nature of images in a media-saturated world. What does it mean to search for the soul of a place, or a person, or an art form, when everything seems to be in flux?

### Final Thoughts

Tokyo-Ga is less a documentary about Tokyo and more a reflection prompted by Tokyo. It’s patient, observant, and deeply personal. It rewards viewers willing to sink into its contemplative rhythm and join Wenders on his thoughtful pilgrimage. It's a film that stays with you, not because of dramatic twists, but because of the quiet resonance of its images and the sincerity of its quest.

Rating: 9/10

This score reflects the film's unique power as a meditative cinematic essay, a touching tribute, and a fascinating time capsule. Its deliberate pace and lack of conventional narrative might not appeal to everyone, but for those attuned to its frequency, it offers profound rewards. It perfectly captures that feeling of searching for something profound in the modern world, a quest that feels timeless even filtered through the specific lens of 1980s Tokyo. It makes you wonder: what ghosts of the past are we searching for in our own rapidly changing landscapes?