It began not on flickering videotape, but on the glossy pages of Life magazine. The year was 1983, and photographer Mary Ellen Mark, alongside writer Cheryl McCall, delivered a gut-wrenching photo essay titled "Streets of the Lost," documenting the lives of homeless teenagers scraping by on the margins of Seattle. The images were stark, unforgettable. A year later, those static frames burst into motion with Martin Bell's devastating documentary, Streetwise, bringing the harsh realities captured by Mark's lens into an even more visceral focus. Renting this tape, tucked perhaps incongruously between action blockbusters and neon-drenched comedies on the video store shelf, was often an accidental encounter with a profoundly different kind of cinema.

The Concrete Jungle Gym

Streetwise isn't a narrative constructed in a writer's room; it's reality observed, unvarnished and often uncomfortable. Bell and his small crew, including Mark who served as associate producer and stills photographer, immersed themselves in the world of kids navigating pimps, prostitution, drug use, petty crime, and the constant search for food, shelter, and some semblance of connection. There’s no heavy-handed narration telling us what to think, no overt political agenda being pushed. Instead, the camera acts as a silent witness, letting the subjects speak for themselves, their voices raw, their actions unfiltered. The Seattle depicted here isn't the grunge-era mecca or the tech hub it would become; it's a grey, damp, often indifferent landscape against which these young lives play out with alarming precarity. It forces us to ask: how does childhood end, or does it sometimes never even get a chance to begin?

Faces You Don't Forget

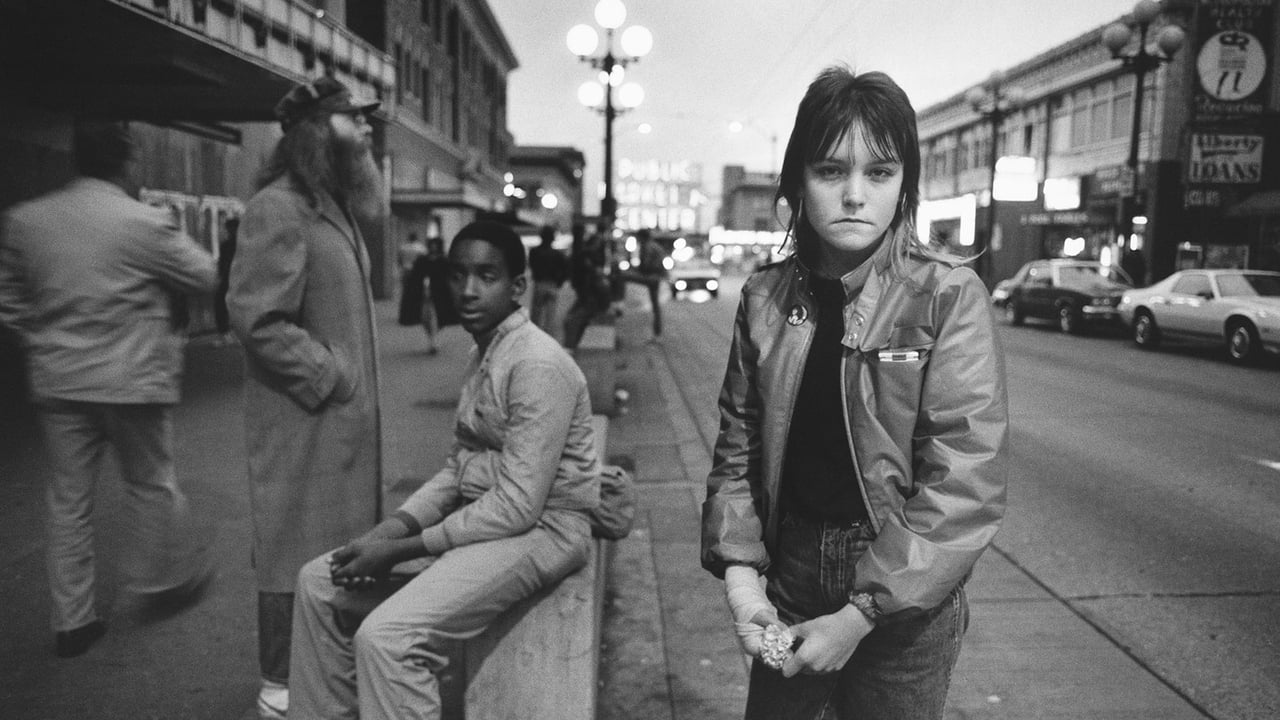

The film's enduring power lies in the unforgettable personalities it captures. Foremost among them is Erin Blackwell, better known as "Tiny." Fourteen years old but projecting an unnerving world-weariness, Tiny dreams of horses and diamonds while navigating the brutal transactions of street life, often turning tricks to survive. Her vulnerability, masked by a tough exterior and layers of makeup, is heartbreaking. Her conversations with her often-absent, alcoholic mother are among the film's most difficult moments, revealing cycles of neglect and desperation. I recall watching Tiny back in the day, her resilience feeling both inspiring and deeply tragic – a paradox that still lingers.

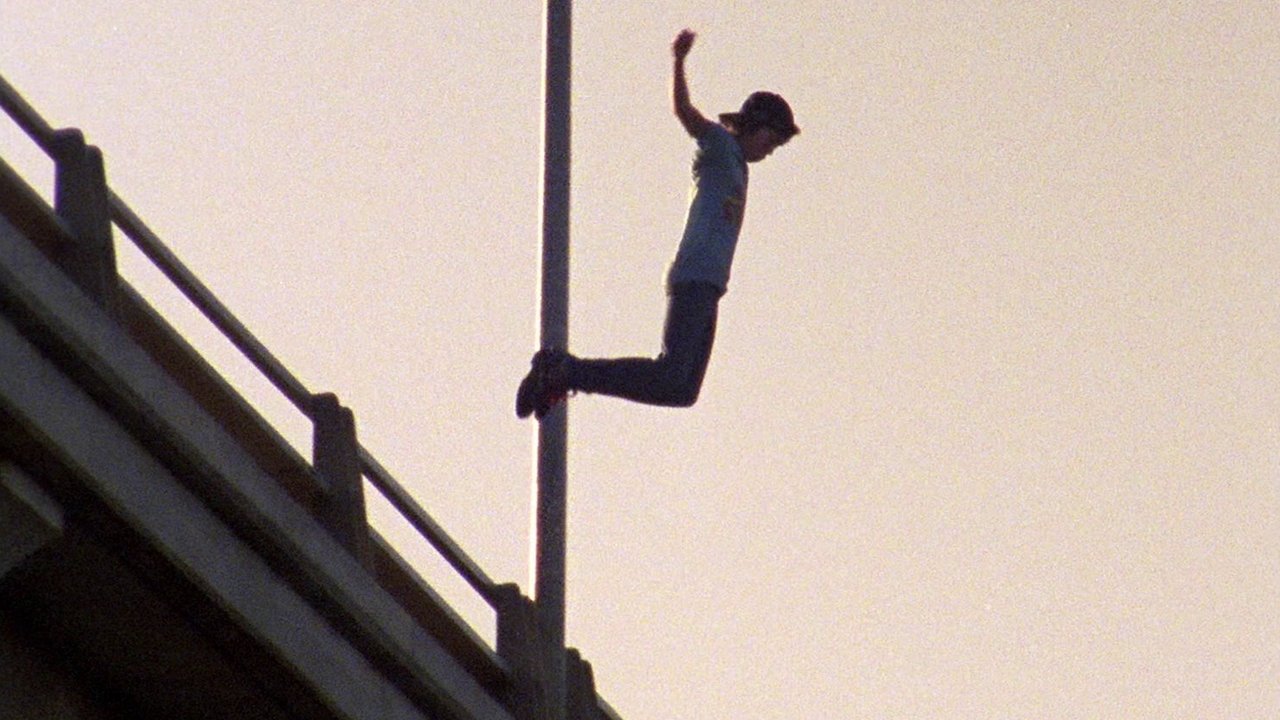

Then there's Dewayne Pomeroy, a fragile boy struggling with his father's imprisonment and his own desperate acts, including a devastating suicide attempt shown with harrowing directness. His story serves as a stark reminder of the immense pressure and lack of support these kids faced. And "Rat," the dumpster-diving survivor, embodies a certain street pragmatism, resourceful yet seemingly resigned to his environment. These aren't just subjects; they feel like fully realised individuals trapped in circumstances beyond their control. Their honesty, their bravado, their moments of childlike joy amidst the squalor – it all feels painfully authentic. What does it say about a society when children are forced into such premature, harsh adulthood?

A Collaboration Born of Trust

The intimacy achieved by Martin Bell is remarkable, clearly built on the trust Mary Ellen Mark had already established with these kids during her photo assignments. This wasn't simply a crew dropping in; it was an extension of Mark's long-term engagement. The cinéma vérité style allows moments to unfold naturally, capturing the rhythms and textures of street existence without imposing judgment. It's a testament to the filmmakers' approach that these vulnerable young people allowed such unflinching access into their lives. Reportedly filmed over several months with a minimal crew, the production itself mirrored the resourcefulness of its subjects, adapting to the unpredictable nature of their world. While critically lauded and earning an Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary Feature, Streetwise wasn't destined for blockbuster status. Its power wasn't in escapism, but in confrontation.

Echoes Through Time

Watching Streetwise today, decades removed from its initial release, is still a powerful experience. The 80s setting – the clothes, the cars, the specific Seattle locations – firmly roots it in the VHS era, a time capsule of a specific urban landscape. Yet, the core issues feel tragically contemporary. Youth homelessness, poverty, addiction, the failures of social safety nets... these problems haven't vanished. If anything, the film serves as a stark baseline, prompting reflection on how much, or how little, has truly changed. Does encountering such raw reality on screen spur empathy, or does it risk becoming just another difficult story we eventually file away?

The film's legacy extends beyond its initial impact. Mary Ellen Mark continued to photograph Tiny for decades, creating a longitudinal study of a life shaped by those early years on the street, culminating in the book and film Tiny: The Life of Erin Blackwell. This follow-up adds another layer of poignancy to the original Streetwise, reminding us that the stories didn't end when the credits rolled.

***

Rating: 9/10

Streetwise is more than just a documentary; it's a vital, humane, and deeply unsettling portrait of lives lived on the edge. Its power comes not from stylistic flourishes, but from its unflinching honesty and the unforgettable resilience and vulnerability of its young subjects. The observational style and the palpable trust between filmmakers and subjects create an intimacy that is both rare and essential. While undeniably difficult viewing, its rawness is precisely why it remains such a significant piece of filmmaking from the era – a stark counterpoint to 80s excess, found perhaps unexpectedly on the shelves of "VHS Heaven." It stays with you, forcing uncomfortable questions long after the tape has ejected. What responsibility do we bear for the forgotten children in our own cities, then and now?