Finding Derek Jarman's Caravaggio on a grainy VHS tape, perhaps nestled in the slightly intimidating 'Art House' section of the local video store, felt like uncovering a secret. It wasn't the explosive action or creature feature fare that dominated the shelves, but something else entirely – a film that moved like drying paint, thick with atmosphere and saturated with the same dramatic light and shadow that defined its subject's revolutionary art. This 1986 biopic wasn't merely about the tumultuous life of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio; it felt steeped in his very essence, a celluloid canvas reflecting the artist's volatile genius and the raw, often brutal, beauty he captured.

Life as Living Canvas

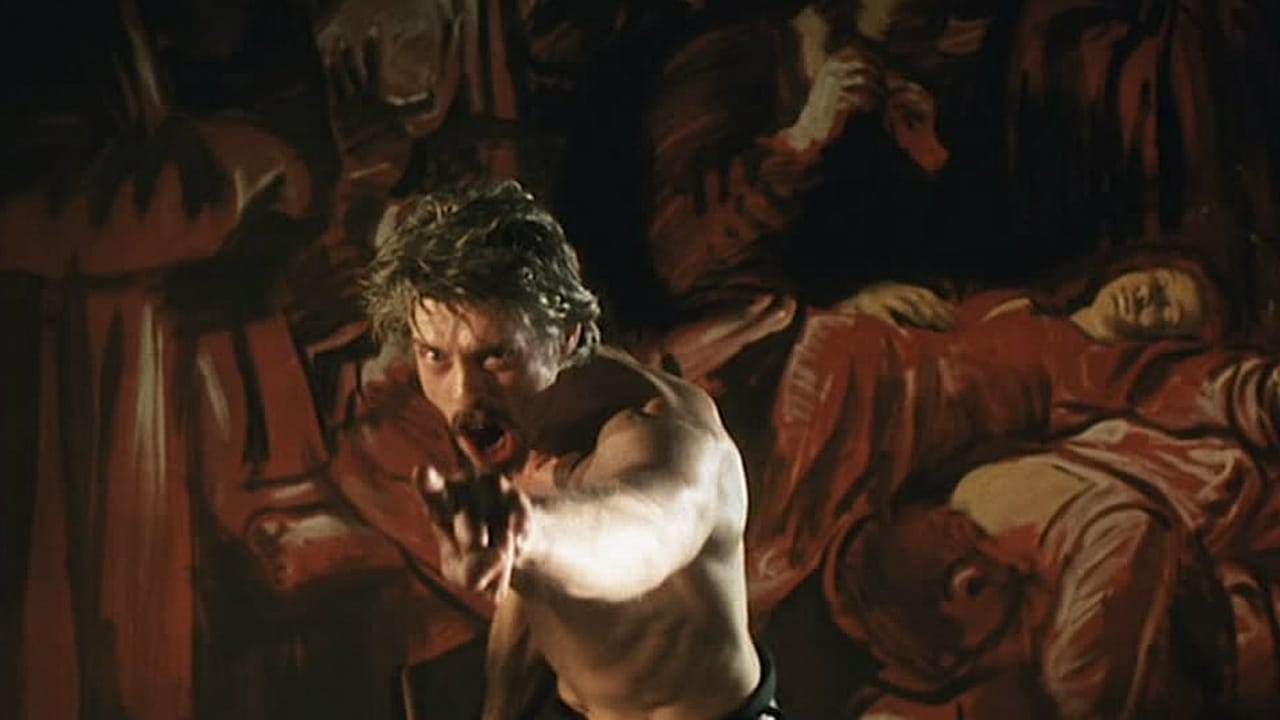

Derek Jarman, himself a painter before becoming a filmmaker (a path less travelled, giving him a unique perspective shared perhaps only by someone like David Lynch, another art school alumnus), doesn't approach biography in the conventional sense. Forget a linear, fact-checked timeline. Instead, Caravaggio unfolds as a series of intense, beautifully composed vignettes, almost like living tableaux vivants mimicking the master's style. We witness Caravaggio (a mesmerizing Nigel Terry) on his deathbed, feverishly recalling key moments – his arrival in Rome, his patronage by the Church, his passionate and fraught relationships with the street fighter Ranuccio Thomasoni (Sean Bean in a remarkably raw early role) and the model Lena (Tilda Swinton, making an unforgettable screen debut).

The film breathes the artist's signature chiaroscuro – the stark contrast between light and deep shadow. Jarman, working with cinematographer Gabriel Beristain, doesn't just replicate the look; he internalizes it. Light falls selectively, sculpting faces out of the gloom, highlighting the texture of rough fabric or the gleam of sweat on skin. It mirrors the internal landscape of Caravaggio himself: a man caught between the sacred commissions of cardinals and the profane realities of tavern brawls and street life, between spiritual yearning and carnal desire.

Flesh, Blood, and Pigment

The performances are central to the film's hypnotic power. Nigel Terry, who many might remember as King Arthur in Excalibur (1981), embodies Caravaggio not just as a historical figure, but as a conduit for intense, often contradictory emotions. His eyes hold both artistic fervor and a deep-seated weariness, his voice capable of smooth persuasion or sudden violence. He makes the artist’s obsessive dedication and self-destructive impulses feel tragically intertwined.

Then there are the figures caught in his orbit. A young Sean Bean brings a brooding physicality and surprising vulnerability to Ranuccio, the lover, model, and possibly betrayer. You see the seeds of the complex, often doomed characters he would later perfect. And Tilda Swinton as Lena is a revelation. Even here, in her first feature film role, she possesses that unique, androgynous screen presence – intelligent, watchful, and slightly ethereal, yet grounded in a tangible reality. Her connection with both Caravaggio and Ranuccio forms the film's emotional triangle, a messy, passionate entanglement that feels dangerously real. The chemistry between the three leads is palpable, charged with unspoken tensions and desires that Jarman allows to simmer just beneath the surface.

Retro Fun Facts: Painting with Pennies

Part of Caravaggio's unique aesthetic was born from necessity. Jarman, ever the resourceful independent filmmaker, worked with a famously tight budget (reportedly around £450,000, a shoestring even then). This constraint arguably fueled the film's visual ingenuity. Unable to afford sprawling sets recreating 17th-century Rome, he opted for suggestive, studio-bound environments, relying on darkness, pools of light, and meticulously arranged props (fruit, fabrics, skulls – motifs straight from Caravaggio's paintings) to evoke the era. This forced minimalism enhances the painterly quality, making each frame feel deliberate and composed.

Jarman also playfully inserts anachronisms – a typewriter clacking away, a truck rumbling in the background, modern costume elements. Far from being errors, these are deliberate choices, suggesting that the themes of passion, power, class struggle, and artistic compromise explored in Caravaggio's time resonate across history, bleeding into our own present. It's a technique Jarman would continue to explore, challenging the very notion of the traditional period drama. It’s also worth noting this was the first of seven collaborations between Jarman and Swinton, a partnership that would become central to British avant-garde cinema.

Beyond Biography

What lingers long after the tape clicks off isn't just the story of one artist, but the questions Jarman raises about the very nature of creation. Where does art end and life begin? What is the price of translating raw human experience – love, violence, poverty, desire – into lasting images? The film doesn't offer easy answers, preferring ambiguity and atmosphere over neat exposition. Its pacing is deliberate, meditative, demanding patience but rewarding it with scenes of striking visual poetry and raw emotional honesty. It explores the complex homoerotic undercurrents in Caravaggio's life and art with a sensitivity and directness rare for its time, reflecting Jarman's own experiences and activism as a gay man.

This isn't a film you pop in for casual viewing; it requires attention, an openness to its unconventional rhythm and visual language. It’s a film that makes you feel the texture of the past, the heat of creation, the chill of mortality. Rediscovering it now, perhaps on a format clearer than that old VHS tape, its power remains undimmed. Jarman crafted something truly unique – a portrait of an artist that feels less like a documentary and more like channeling his ghost through light and shadow.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's stunning visual artistry, powerful central performances, and audacious, deeply personal approach to biographical filmmaking. It's a challenging, sometimes opaque film, and its deliberate pace won't appeal to all, preventing a higher score. However, its unique atmosphere and thematic depth make it a standout piece of 80s independent cinema, brilliantly capturing the spirit, if not the strict letter, of its subject's life.

Caravaggio remains a potent reminder that cinema, like painting, can transcend mere representation to touch something deeper about the human condition, leaving images seared into the memory long after the screen fades to black.