Here’s a review for VHS Heaven:

***

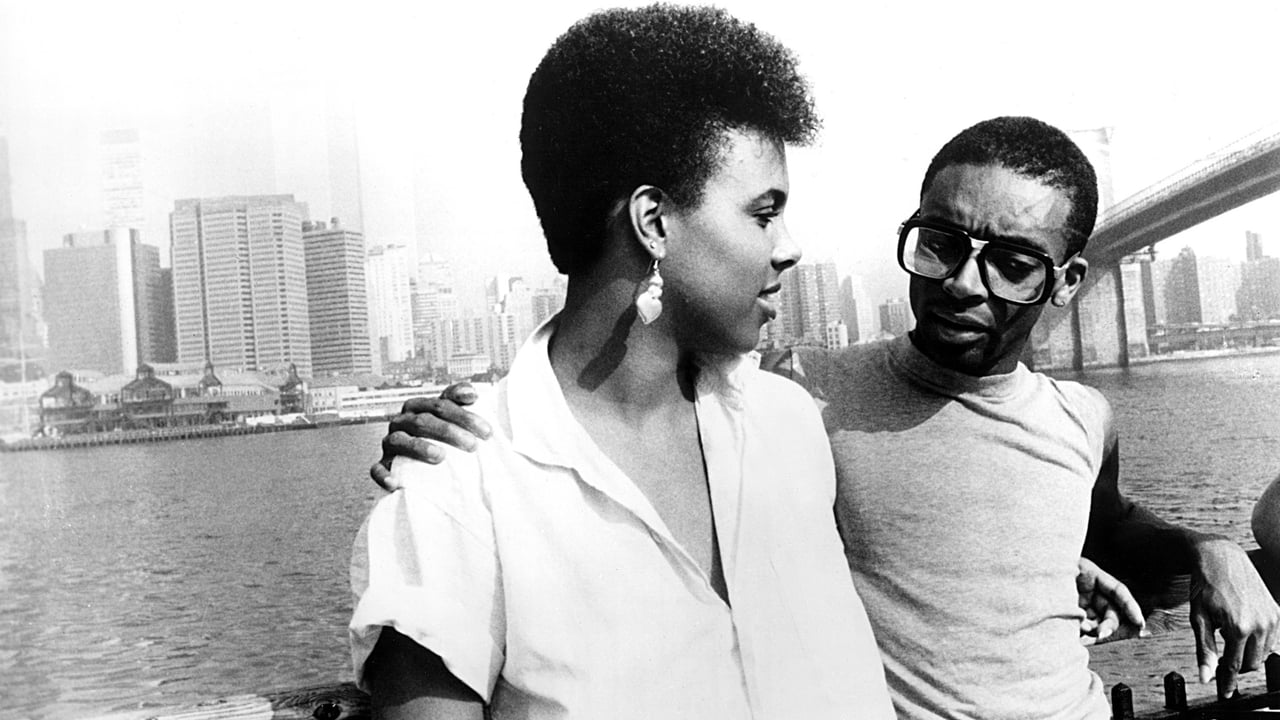

She wasn't asking for permission. That’s the first thing that hits you about Nola Darling, the magnetic center of Spike Lee's explosive 1986 debut, She's Gotta Have It. In an era often defined by straightforward Hollywood narratives, here was a film, shot mostly in stark, vibrant black and white, focusing unapologetically on a young Black woman in Brooklyn juggling three distinct lovers, not out of malice or manipulation, but because she genuinely finds something valuable in each of them. It felt revolutionary slipping that tape into the VCR back then, a breath of fresh, complicated air amidst the blockbuster sequels and high-concept comedies dominating the rental shelves.

A Woman's Prerogative

Played with captivating self-possession by Tracy Camilla Johns, Nola Darling isn't presented as a victim or a villainess. She’s an artist navigating her desires and the expectations society – and her lovers – place upon her. The film grants her the narrative space, quite literally through direct-to-camera confessions, to explore her own complex feelings about sex, freedom, and commitment. It asks questions that still resonate: Why should a woman's desire for variety be judged more harshly than a man's? Can you truly love more than one person simultaneously? The film doesn't offer easy answers, preferring instead to immerse us in Nola's world and let us grapple with the implications alongside her.

The Suitors: A Study in Contrasts

Nola's trio of lovers couldn't be more different, each representing a potential path. There's Jamie Overstreet (Tommy Redmond Hicks), the dependable, seemingly stable "nice guy" who offers security but perhaps lacks excitement. Hicks imbues Jamie with a quiet sensitivity that makes his eventual possessiveness feel like a betrayal of his initial promise. Then there's Greer Childs (John Canada Terrell), the wealthy, narcissistic model obsessed with status and his own reflection. Terrell leans into Greer’s arrogance with relish, making him infuriatingly captivating – a perfect caricature of superficiality.

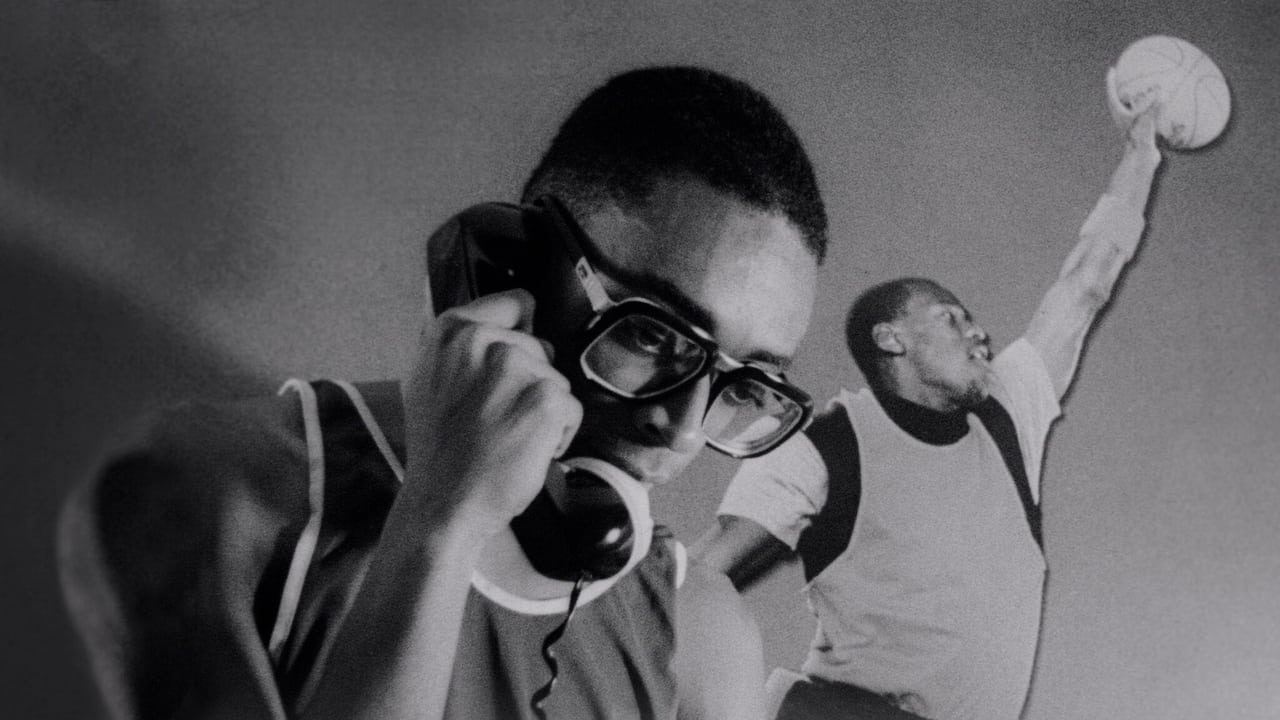

And, of course, there's Mars Blackmon, played by Spike Lee himself. The fast-talking, bicycle-riding, gold-chain-wearing B-boy sneakerhead became an instant icon ("Please baby, please baby, please baby baby baby please!"). Mars is immature, often clownish, yet possesses a certain raw energy and humor that clearly appeals to Nola. It's a star-making turn, even in a supporting role, launching a character who would famously leap from indie cinema to Nike commercials alongside Michael Jordan. Lee's performance is a bundle of nervous energy and surprising charm.

Brooklyn Grit, Indie Fire ("Retro Fun Facts")

Part of the enduring appeal of She's Gotta Have It lies in its palpable indie spirit. This wasn't slick Hollywood filmmaking; this was raw, resourceful storytelling born from necessity. Filmed on location in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, over just 12 days, the production had a minuscule budget – sources cite around $175,000 – cobbled together from grants, determination, and even seed money from Lee's grandmother. You can almost feel the kinetic energy of that compressed schedule pulsating through the frames. The predominantly black-and-white cinematography wasn't just an aesthetic choice; it was partly a budgetary one, though Lee uses it brilliantly to create a timeless, almost documentary feel.

Interestingly, the film's sole color sequence – Nola's vibrant birthday dance – wasn't initially planned. It was added later when a bit more funding materialized, offering a splash of visual warmth amidst the monochrome narrative. This resourcefulness extended to battling the MPAA; Lee had to trim some of the film's frank depictions of sexuality to avoid the dreaded 'X' rating, eventually securing an 'R'. Despite these hurdles, the film became a critical and commercial sensation, grossing over $7 million domestically – a phenomenal return on investment that announced Spike Lee, fresh out of NYU film school, as a major new voice in American cinema, paving the way for his prolific career, including classics like Do the Right Thing (1989) and Malcolm X (1992).

A Complicated Legacy

Spike Lee's directorial confidence is evident even here. The direct address, the blending of humor and drama, the willingness to tackle provocative themes head-on – these became hallmarks of his style. The film remains a landmark achievement for independent filmmaking and Black cinema, portraying contemporary Black life with a specificity and intimacy rarely seen on screen at the time. It fearlessly centered a Black woman's sexual agency, sparking conversations that continue today, evidenced by the recent Netflix series adaptation helmed once again by Lee.

However, no reflection on She's Gotta Have It is complete without acknowledging its most controversial element. Spoiler Alert! The sequence where Jamie essentially forces himself on Nola, framed almost as a twisted solution to her "indecision," remains deeply problematic and jarring. It clashes uneasily with the film's otherwise celebratory tone regarding Nola's freedom. Lee himself has expressed regret over this scene in later years, acknowledging its problematic nature. It's a significant flaw that complicates the film's feminist reading, reminding us that even groundbreaking works can carry the problematic perspectives of their time.

The Verdict

Watching She's Gotta Have It today is still a potent experience. It crackles with the energy of discovery – a young filmmaker finding his voice, a culture finding its representation, and a character demanding her truth. The performances feel authentic, the dialogue sharp, and the questions it poses about love, sex, and independence linger long after the credits roll. Its low-budget origins are part of its charm, a testament to the power of vision over resources.

Rating: 8/10

This score reflects the film's undeniable historical significance, its bold premise, vibrant characters (especially the iconic Mars Blackmon), and its role in launching Spike Lee's vital career. It captures a specific time and place with infectious energy. The rating is tempered slightly by the undeniable discomfort of the ending sequence and the occasional roughness inherent in its ultra-low-budget production, but its importance and overall impact remain profound. It's a film that doesn't just entertain; it demands engagement and conversation, a quality that ensures its place not just in VHS heaven, but in cinema history. What does Nola truly want? Maybe the point was always her right to figure that out for herself.