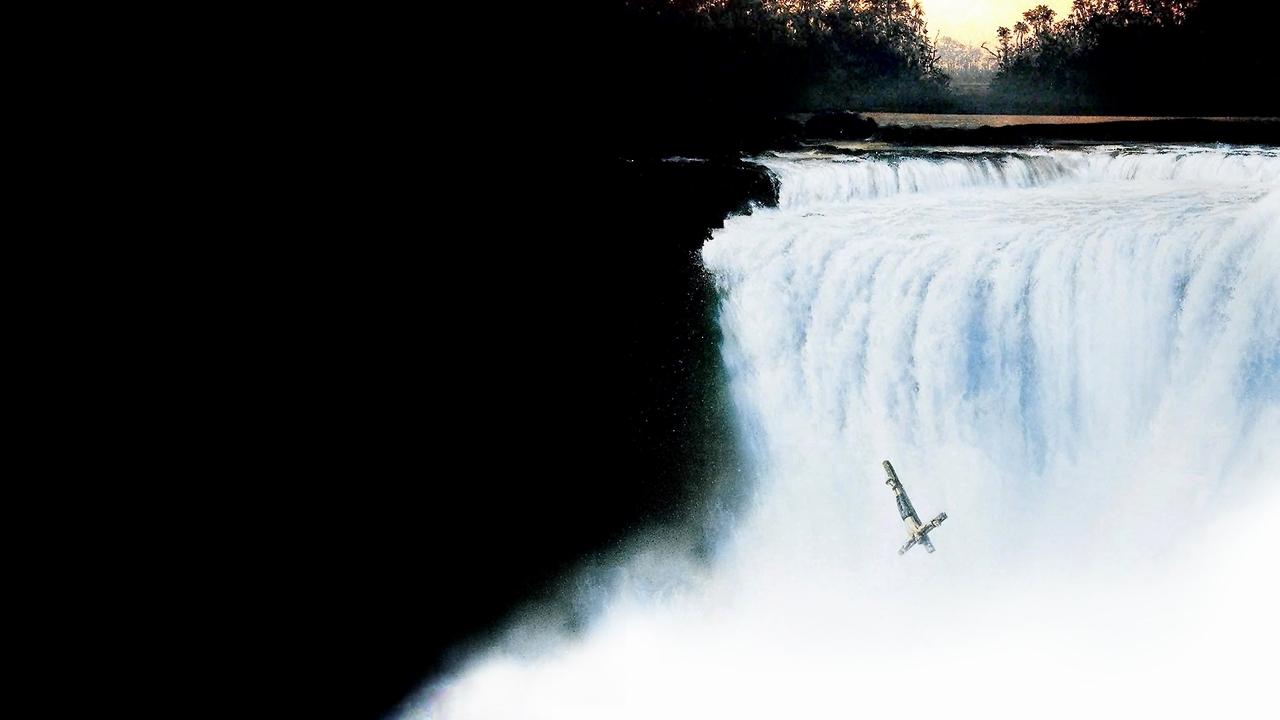

It begins with an image of almost unbearable sacrifice and defiance: a lone figure, crucified, tumbling through the mists and churning water of the immense Iguazu Falls. This opening to Roland Joffé's 1986 masterpiece, The Mission, isn't just spectacle; it's a stark visual overture for the profound questions about faith, colonialism, conscience, and the brutal collision of worlds that echo long after the credits roll. Watching it again recently, decades after first encountering its grandeur on a flickering CRT via a well-worn VHS tape, that image retains every bit of its haunting power.

Where Heaven Meets Earth, and Politics Intervenes

Set in the mid-18th century jungles of South America, The Mission plunges us into the complex reality of Jesuit missionaries attempting to protect indigenous Guarani tribes from Portuguese colonial exploitation. Penned by the legendary Robert Bolt (whose quill gave us epics like Lawrence of Arabia (1962) and A Man for All Seasons (1966)), the script masterfully avoids easy answers. It lays bare the political machinations between Spain, Portugal, and the Vatican, embodied by the conflicted Papal emissary Cardinal Altamirano (Ray McAnally in a performance of subtle, weary authority). His narration frames the story, lending it a tone of somber reflection – a report back to a power far removed from the raw humanity at stake. The historical backdrop, specifically the Treaty of Madrid (1750) which transferred territory and sealed the missions' fate, isn't just context; it's the crushing engine driving the narrative.

Two Paths, One Cross

At the heart of the film lie two towering figures, portrayed with career-defining depth by Jeremy Irons and Robert De Niro. Irons is Father Gabriel, a man of unwavering pacifist faith, whose connection with the Guarani is forged through the universal language of music – specifically, the haunting notes of his oboe. Irons embodies a serene, almost ethereal conviction; his spirituality feels lived-in, genuine. His methods are rooted in love, understanding, and a belief in the inherent goodness of the people he serves. He believes the word of God is shield enough.

Contrast this with De Niro's Rodrigo Mendoza. We first meet him as a mercenary and slaver, clad in armour, his face a mask of hardened pragmatism and simmering violence. After a devastating personal tragedy born from his own rage, Mendoza seeks penance in the most physically demanding way possible – hauling his own armour and weapons up the treacherous cliffs to the mission he once preyed upon. De Niro's transformation is staggering. The physicality of his penance is palpable, but it's the slow thawing of his soul, the acceptance by the very people he harmed, that truly resonates. When the political vise tightens, Mendoza finds he cannot stand idly by. He renounces his vows (or perhaps reclaims his former self) to take up arms alongside the Guarani, believing righteous force is the only answer. It's a credit to both actors and Joffé's direction (hot off the similarly challenging The Killing Fields (1984)) that both paths feel valid, both choices agonizingly human. Whose mission is truer? The film wisely refuses to say.

The Sound and the Fury

You simply cannot discuss The Mission without dwelling on two monumental artistic achievements: the cinematography and the score. Chris Menges, who deservedly won an Oscar for his work here, captures the overwhelming majesty and danger of the South American landscape. The Iguazu Falls aren't just a backdrop; they are a character – beautiful, terrifying, indifferent. The scenes within the missions, bathed in natural light, possess a painterly quality, contrasting sharply with the encroaching shadows of political expediency. Filming on location presented immense logistical challenges, hauling equipment through dense jungle and dealing with the unpredictable environment, but the authenticity it lends is undeniable.

And then there is Ennio Morricone's score. It's almost impossible to overstate its impact. It's one of those rare soundtracks that transcends the film itself, becoming an iconic piece of music in its own right. Combining liturgical choirs, indigenous flute melodies, and soaring orchestral themes, Morricone creates an auditory landscape that perfectly mirrors the film's fusion of cultures and clash of ideologies. Reportedly, Morricone initially felt the film was powerful enough without music, a testament to Joffé's visuals, but thankfully he was persuaded. The score is heartbreaking, uplifting, and utterly unforgettable – the soul of the film given voice. It feels less like a score added to the film and more like something discovered within it.

Retro Reflections and Enduring Questions

Seeing The Mission in the 80s felt different. Amidst the high-octane action and synth-pop soundtracks, here was a sprawling, serious historical epic tackling complex moral theology and the grim realities of colonialism. It demanded patience, attention, and a willingness to grapple with ambiguity. The film's budget was substantial for the time (around $24.5 million), and while it won the prestigious Palme d'Or at Cannes, it wasn't a massive box office smash, perhaps proving a little too contemplative for mainstream tastes then. Yet, its reputation has only grown.

What lingers most profoundly is the film's exploration of conscience under pressure. What does it mean to truly serve? When does faith demand pacifism, and when might it demand resistance? Altamirano’s closing lines, delivered with profound sadness by McAnally, resonate with chilling timelessness: "Thus were the Guarani people destroyed... And thus have I died, and they live? No, Your Holiness. Thus have they died, and I live." He acknowledges the political 'necessity' but is forever haunted by the human cost. It forces us to ask: faced with such injustice, what path would we choose? Gabriel's or Mendoza's?

Rating: 9/10

The Mission is a towering achievement of 80s cinema, a film of breathtaking beauty, profound thematic depth, and unforgettable performances. The score and cinematography alone make it essential viewing. While its deliberate pace and challenging subject matter demand engagement, the rewards are immense. The 9 rating reflects its near-perfect execution in capturing a complex historical moment with artistry and soul, slightly tempered only by the fact its meditative nature might not connect with every viewer expecting conventional epic thrills.

It remains a powerful, haunting film that stays with you, a reminder captured on celluloid (and preserved on those chunky VHS tapes) of the enduring struggle between the spirit's aspirations and the world's harsh realities.