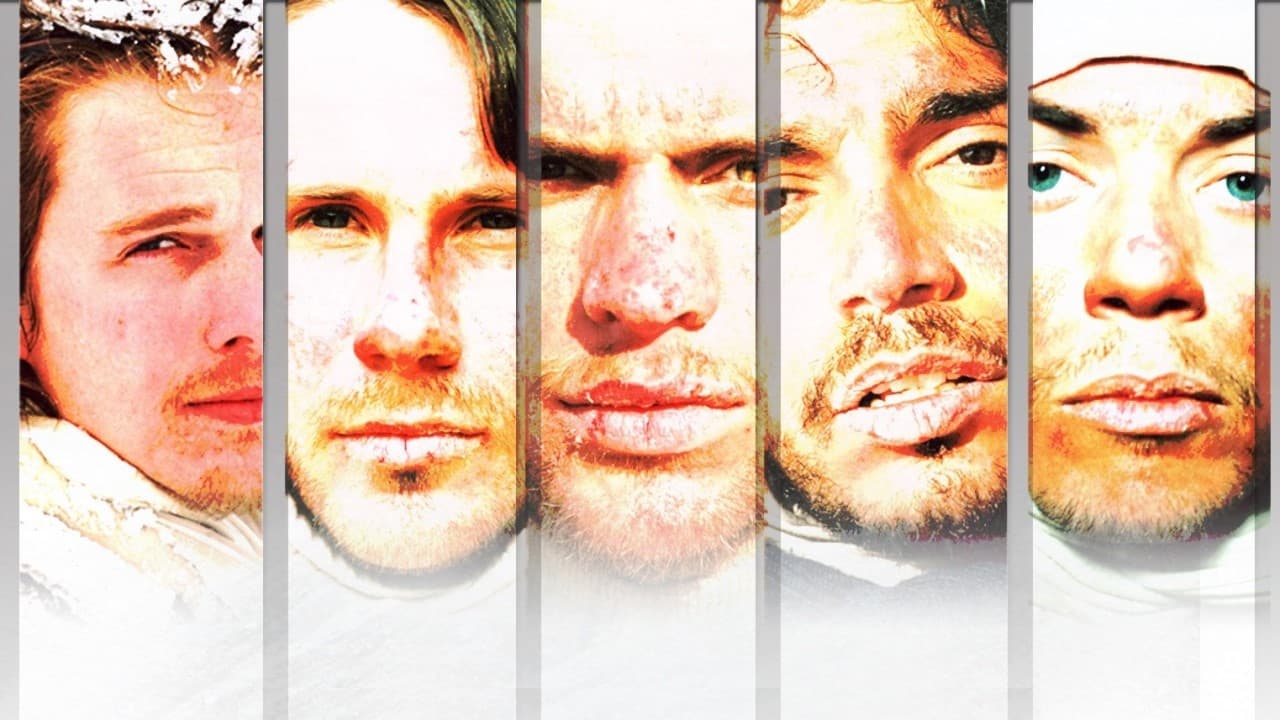

It begins not with the crash, but with a photograph. A moment frozen in time – young men, full of life, camaraderie radiating from the faded image. This quiet opening to Frank Marshall’s 1993 film Alive serves as a stark, poignant counterpoint to the harrowing ordeal that follows, forcing us immediately to confront the fragility of the very vitality we see on screen. This isn't just a disaster movie; it's a meditation on the sheer tenacity of the human will when stripped bare.

I recall renting Alive from the local video store, perhaps drawn by the promise of a survival thriller, but unprepared for the profound questions it would lodge in my mind. Based on Piers Paul Read’s meticulous account of the 1972 Andes flight disaster, the film plunges us, alongside the members of that Uruguayan rugby team and their families, into an unimaginable nightmare.

Into the White Hell

Marshall, who had previously navigated thrills and chills with Arachnophobia (1990), directs the crash sequence with terrifying immediacy. Even now, viewed on a screen far removed from the CRT TVs of the 90s, the sequence retains its power. The sudden, brutal transition from normalcy to chaos – the shearing metal, the screams, the sickening lurch – is masterfully handled. Reportedly, filming this sequence involved complex practical effects and stunt coordination, aiming for a realism that grounds the subsequent struggle. Shot largely in the snowy Purcell Mountains of British Columbia, the film effectively conveys the crushing isolation and alien hostility of the Andes landscape. The biting wind, the blinding white, the profound silence broken only by the elements – it becomes another character, an antagonist indifferent to the suffering it harbours.

The Weight of Survival

Where Alive truly distinguishes itself is in its unflinching, yet sensitive, portrayal of the survivors' physical and psychological disintegration. The initial shock gives way to resourcefulness, then dwindling hope, and finally, the agonizing realization of their predicament. We see the faith of characters like Antonio (Vincent Spano) tested, the leadership emerge from unexpected corners, and the devastating toll of loss etched onto young faces. Ethan Hawke, as Nando Parrado, delivers a performance that feels pivotal, capturing the transformation from a carefree young man to one driven by an almost primal need to return home. His journey, spurred by immense personal loss, becomes the narrative's backbone. Josh Hamilton as Roberto Canessa provides a compelling counterpoint – pragmatic, medically knowledgeable, and wrestling differently with the grim choices ahead.

The film doesn't shy away from the infamous decision the survivors were forced to make: resorting to cannibalism to stay alive. It’s handled not for shock value, but as a deeply somber, necessary threshold crossed out of sheer desperation. The screenplay by John Patrick Shanley (known for vastly different fare like Moonstruck (1987)) adapts this most difficult aspect of the true story with a focus on the moral and spiritual anguish involved. Knowing that real survivors, including Nando Parrado himself, served as technical advisors lends an undeniable authenticity and weight to these scenes. You feel the characters' revulsion, their prayers, their justification – it’s a harrowing depiction of humanity pushed beyond conceivable limits. It wasn’t just the script; the actors reportedly endured challenging conditions, including weight loss regimes, to better reflect the survivors' ordeal, adding another layer to the film's visceral impact.

More Than Just a Story

Beyond the central trio, the ensemble cast effectively portrays the group dynamic – the moments of shared grief, the flickering embers of hope, the inevitable friction born of despair. The score by James Newton Howard underscores the emotional landscape beautifully, shifting from jarring dissonance during the crash to moments of quiet solemnity and, eventually, soaring hope during the film's climax.

Alive wasn't a massive blockbuster (grossing around $36.7 million domestically on a $32 million budget), perhaps due to its demanding subject matter. Yet, its impact lingers. It sits apart from more sensationalist disaster flicks, offering a more profound exploration of faith, ethics, and the raw instinct to survive. It forces uncomfortable questions: What lines would we cross? What reserves of strength lie dormant within us?

While the film primarily focuses on the ordeal in the mountains, it’s worth noting the existence of other adaptations, including the earlier Mexican film Supervivientes de los Andes (1976) and the excellent later documentary Stranded: I've Come from a Plane That Crashed on the Mountain (2007), which features interviews with the actual survivors, offering even deeper insight.

Rating: 8/10

Alive earns its high marks not for being an easy watch, but for its power and integrity. The performances, particularly from Hawke, Spano, and Hamilton, feel achingly real. Marshall's direction balances the spectacle of disaster with the intimate human drama effectively. The film confronts its most difficult subject matter head-on but with respect, focusing on the psychological and spiritual cost of survival. It's a harrowing, draining experience, yet ultimately one that speaks volumes about human endurance against impossible odds. It’s a film that stays with you, long after the VCR heads stopped spinning – a chilling reminder of what we can endure, and the difficult choices survival sometimes demands. What truly defines humanity when everything else is stripped away? Alive offers a stark, unforgettable perspective.