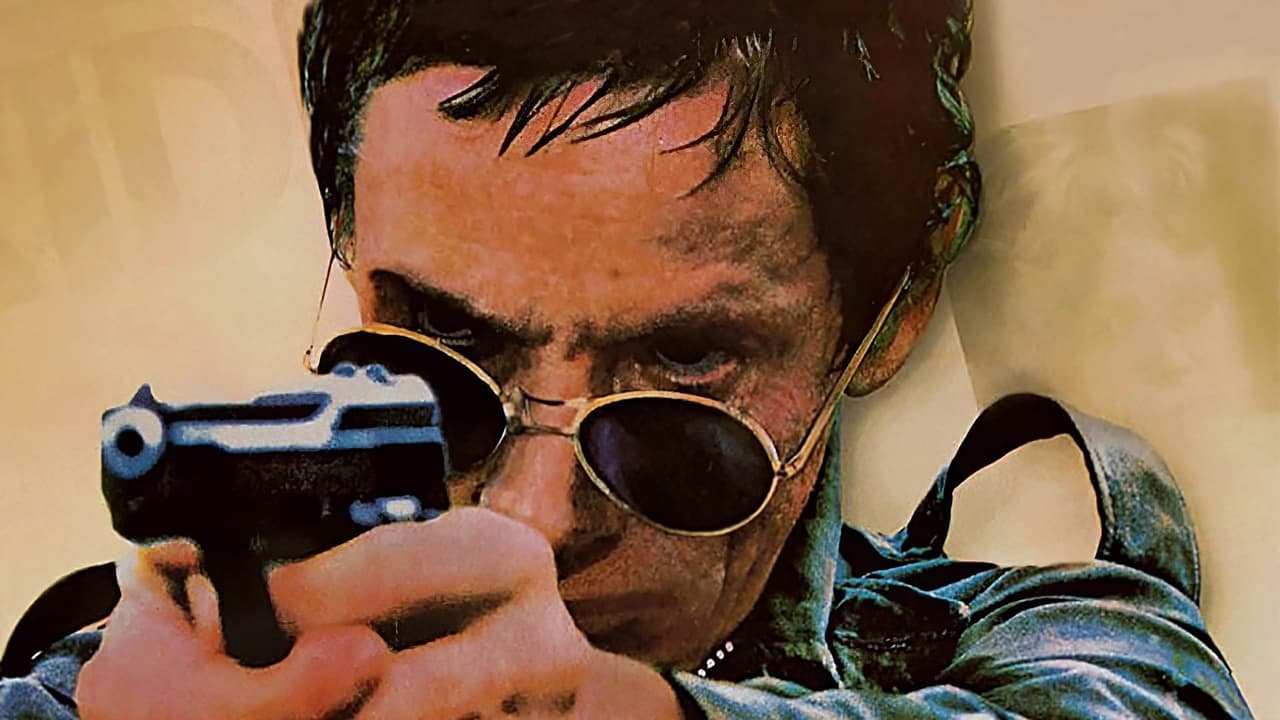

There's a certain kind of quiet intensity that characterized some thrillers of the late 80s, a simmering unease beneath a sun-drenched European surface. Before the explosive, stylized vengeance of Tony Scott’s 2004 remake became the definitive version for many, there was Élie Chouraqui's 1987 Man on Fire. Watching it again now, pulled from the dusty shelves of memory much like retrieving a well-worn VHS tape, reveals a film less concerned with visceral action and more focused on a wounded soul finding an unexpected anchor. It feels different, perhaps rougher around the edges, but imbued with a distinct, almost melancholy atmosphere that lingers.

A Different Kind of Heat

The setup is familiar to those who know the story, drawn from A. J. Quinnell's popular 1980 novel which had already generated considerable buzz. John Creasy (Scott Glenn), a former CIA operative adrift and haunted by his past, takes a job in Italy as a bodyguard for Samantha "Sam" Balletto (Jade Malle), the young daughter of a wealthy couple navigating the very real threat of kidnapping that plagued affluent families in Italy during that era. The sun-drenched villas and picturesque landscapes of Lake Como, where much of the film was shot, create a deceptive tranquility, a beautiful facade masking potential danger. It’s a world away from the gritty Mexico City of the remake, offering a different, almost dreamlike visual palette. French director Élie Chouraqui, working with veteran Italian screenwriter Sergio Donati (a frequent collaborator with Sergio Leone), leans into this European sensibility, allowing the environment to shape the mood.

The Stillness Before the Storm

What truly distinguishes this version is Scott Glenn's portrayal of Creasy. Where Denzel Washington would later bring a charismatic, outwardly tormented energy, Glenn internalizes Creasy's damage. His performance is remarkably contained, often communicating through weary eyes and subtle shifts in posture rather than dialogue. He embodies a man running on fumes, disillusioned and disconnected. We learn little of his specific past traumas – they exist as a palpable weight, an unspoken burden. Glenn, who had already showcased his knack for intense, reserved characters in films like The Right Stuff (1983) and would later chill audiences in The Silence of the Lambs (1991), is perfectly cast here. His stillness makes the eventual eruption, when it comes, feel earned, less like an action trope and more like the shattering of a fragile dam.

His relationship with Sam forms the film’s emotional core. Jade Malle, in what remains her most notable role, brings a refreshing lack of Hollywood polish to Sam. She’s not precociously quippy; she’s convincingly inquisitive, lonely, and gradually chips away at Creasy’s hardened exterior with genuine childhood curiosity. Their bond develops slowly, organically, built through shared moments of quiet companionship rather than grand pronouncements. It’s this developing connection that gives the film its heart, the slow thaw of Creasy’s frozen spirit. Does this gradual build make the inevitable tragedy hit harder, precisely because it feels so grounded?

Whispers from the Set

While perhaps lacking the sheer kinetic force of its successor, the 1987 Man on Fire possesses its own gritty charm. It feels very much like a product of its time – a mid-budget Euro-thriller aesthetic. Interestingly, Joe Pesci appears in a supporting role as Creasy’s friend David, offering counsel and connections. It’s a pre-Goodfellas (1990) Pesci, sharp and watchful, but without the explosive volatility that would soon define his iconic screen persona. Seeing him here offers a fascinating glimpse of his range before that definitive role. Quinnell's novel was significantly darker and more violent than either film adaptation, and while this version certainly doesn't shy away from brutality in its latter half, it retains a more melancholic, character-driven focus compared to the source material's relentless bleakness. It’s less about the mechanics of revenge and more about the personal cost of violence and the desperate grasp for redemption. The score by John Scott complements this mood, often favouring atmospheric tension over bombastic action cues.

Echoes in the Tape Deck

Rewatching this Man on Fire today, it inevitably exists in the shadow of the 2004 powerhouse. The Tony Scott version is arguably slicker, more intense, and features a towering performance from Washington. Yet, this earlier film offers something different, something quieter but no less potent. It's a mood piece as much as a thriller, a study in contained grief and unexpected connection set against a beautiful, indifferent landscape. It reminds me of discovering these kinds of films on VHS – sometimes you rented the big action hit, other times you stumbled onto something with a different rhythm, something that stayed with you for unexpected reasons. I distinctly remember renting this back in the day, drawn perhaps by Glenn's familiar face from other action roles, and being surprised by its more deliberate pace and emotional weight. It wasn't quite what I expected, but it resonated.

Rating: 7/10

This score reflects a film that succeeds beautifully in establishing atmosphere and features a compellingly understated lead performance from Scott Glenn. The emotional core between Creasy and Sam is genuinely affecting, thanks to Jade Malle's naturalism. While the pacing might feel slow to viewers accustomed to the remake, and its production values are clearly more modest, its strength lies in its focus on character and mood. It’s a solid, atmospheric thriller that deserves to be remembered on its own merits, not just as a footnote to a more famous remake.

It leaves you pondering not just the nature of revenge, but the quiet ways broken people can sometimes find pieces of themselves in the most unexpected connections. A different fire, perhaps, but one that still flickers in the memory.