There’s a certain quality to the light in Jean-Loup Hubert's The Grand Highway (original title: Le Grand Chemin), a hazy, sun-drenched languor that perfectly captures the feeling of a childhood summer stretching out endlessly. Released in 1987, this French gem wasn’t the sort of film blasting from multiplex speakers alongside blockbusters. Instead, it likely found its way into many homes via the quiet hum of a VCR, a discovery perhaps made browsing the 'Foreign Films' section of the local video store. And what a discovery it was – a film that looks idyllic on the surface but carries a profound, melancholic weight just beneath.

A Summer of Awakenings

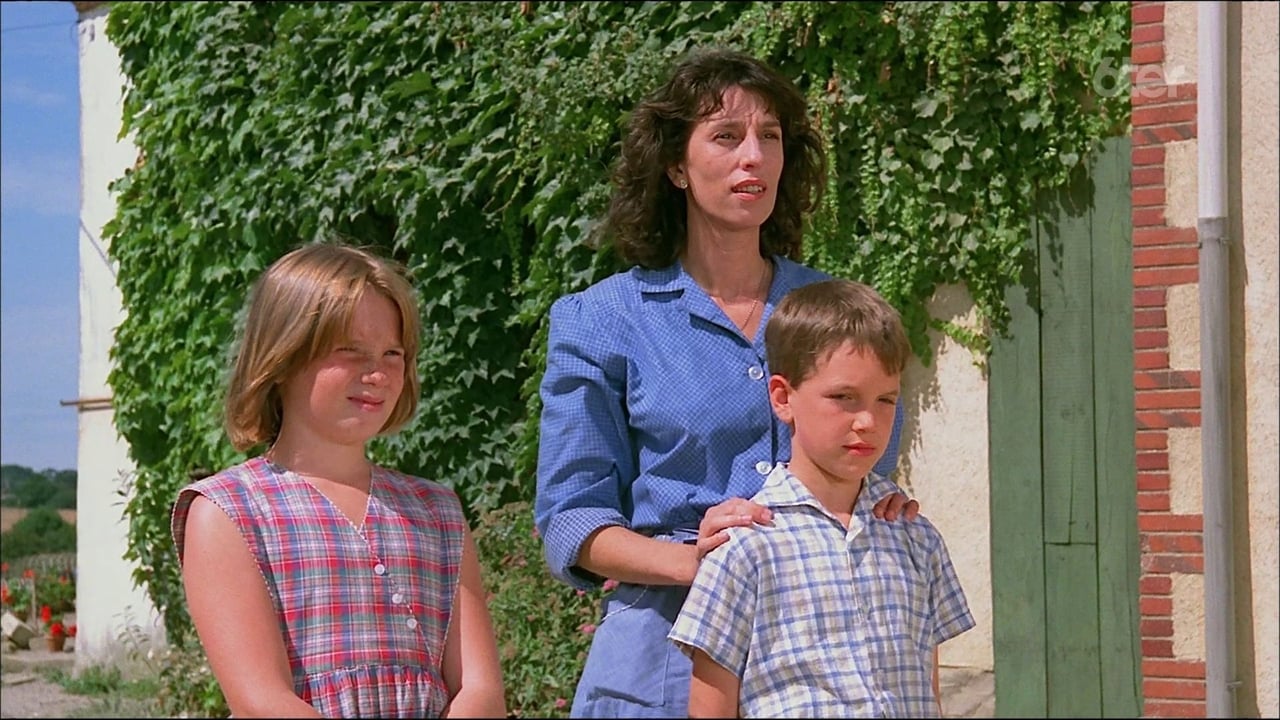

The premise is deceptively simple. Nine-year-old Louis (Antoine Hubert, the director's own son), a sensitive Parisian boy, is sent to spend the summer in a small village in rural Brittany. His heavily pregnant mother needs rest, so Louis is placed in the care of her childhood friend, Marcelle (Anémone), and her husband, Pelo (Richard Bohringer). What unfolds isn't a plot driven by dramatic twists, but rather a delicate observation of Louis navigating a world steeped in unspoken adult sorrows, forging tentative friendships, and experiencing the raw beauty and occasional cruelty of nature and human nature alike. The film unfolds at the pace of that summer – unhurried, allowing moments to breathe, letting the quiet revelations land with gentle force.

Childhood Through a Glass, Darkly

Young Antoine Hubert is remarkably natural as Louis, serving as our wide-eyed guide. Much of the film's power comes from seeing the adult world – particularly the brittle, aching relationship between Marcelle and Pelo – through his observant, often uncomprehending gaze. He witnesses their sharp words, their simmering resentment, Pelo's escapes to the local bar, and Marcelle's tightly wound grief. He doesn’t understand the root cause initially – the devastating loss of their own infant son years prior – but he feels the tension, the pervasive sadness that hangs in the air even on the brightest days. His friendship with the mischievous, slightly older Martine (Vanessa Guedj) provides a wonderful counterpoint – a space for childhood secrets, games played in sun-dappled churchyards, and the first, innocent explorations of difference and connection. Their interactions feel utterly authentic, capturing that unique blend of curiosity and naivete specific to that age.

Performances Forged in Truth

Where The Grand Highway truly ascends is in the staggering performances of its adult leads. Anémone, who rightly won the César Award for Best Actress for this role, is simply devastating as Marcelle. She portrays a woman hollowed out by grief, her smiles brittle, her affection for Louis warring with a protective hardness born of immense pain. There’s a scene where she scrubs floors with a terrifying ferocity that speaks volumes more than any dialogue could. Opposite her, Richard Bohringer, also a César winner for Best Actor here, embodies Pelo's rough-edged masculinity, his gruffness barely concealing a deep well of sorrow and frustration. Pelo finds solace in drink and his work as a blacksmith, but Bohringer lets us see the cracks, the moments of vulnerability, especially in his slowly thawing relationship with Louis. Their chemistry is electric, fraught with the unspoken history that defines their present. Watching them is like observing a wound that refuses to fully heal, a portrayal of long-term grief and marital strain rendered with aching authenticity.

The Soul of Rural France

Director Jean-Loup Hubert, who also penned the sensitive screenplay (which nabbed its own César Award), draws heavily on his own childhood experiences, filming in the very village near Rouans where he spent time as a boy. This personal connection permeates the film. The Breton countryside isn't just a backdrop; it's a living entity, shaping the characters and the narrative. Hubert captures the rhythms of rural life – the cycles of nature, the importance of community (even when fractured), the stark realities alongside the picturesque beauty. There’s a tangible sense of place here, a feeling so strong you can almost smell the damp earth and the woodsmoke. This wasn't a common setting for mainstream films reaching international audiences back then, offering a quiet alternative to the urban landscapes dominating cinema. Its success in France, both critically and commercially, speaks to how deeply it resonated with domestic audiences, perhaps recognizing a truth often overlooked.

A Lasting Resonance

Watching The Grand Highway today, possibly on a format far removed from the well-worn VHS tapes it first graced, its power remains undiminished. It avoids sentimentality, opting instead for a clear-eyed empathy that feels remarkably mature. It reminds us that childhood isn't always an innocent idyll, that children are often silent witnesses to adult complexities they are only beginning to grasp. What does Louis truly understand by summer's end? Perhaps not everything, but he leaves changed, carrying with him the faint echoes of laughter and tears, the scent of the countryside, and the undeniable weight of human connection and loss. Doesn't this quiet observation of life's harder edges feel more truthful than many grander cinematic statements?

Rating: 9/10

The Grand Highway earns this high mark for its profound emotional honesty, the powerhouse performances from Anémone and Bohringer that anchor the film in raw truth, and its beautifully realized sense of place and time. It’s a masterclass in subtle storytelling, allowing complex themes of grief, healing, and childhood awakening to unfold organically. While its deliberate pacing might test some viewers accustomed to faster narratives, its depth and sensitivity are undeniable.

A truly special film, one that lingers like the memory of a long-ago summer – beautiful, poignant, and quietly unforgettable. It’s a reminder that sometimes the most profound stories are whispered, not shouted.