Here we go, another spin in the VCR time machine...

Searching for America, Finding Themselves (Mostly)

There’s a certain kind of ambition that defined the late 80s, wasn't there? A sense of scale, a feeling that boundaries were there to be pushed, sometimes shattered. And few pushed harder, or aimed higher, than U2 at the absolute zenith of their Joshua Tree-fueled global dominance. Watching Phil Joanou’s U2: Rattle and Hum (1988) again after all these years feels like unearthing a time capsule – not just of the band, but of that specific cultural moment. It’s a film wrestling with enormity: the enormity of U2’s fame, the enormity of the American musical landscape they sought to explore, and maybe, just maybe, the enormity of their own earnest self-belief. Does it entirely succeed? That’s still up for debate, decades later.

Monochrome Gods, Colourful Pilgrims

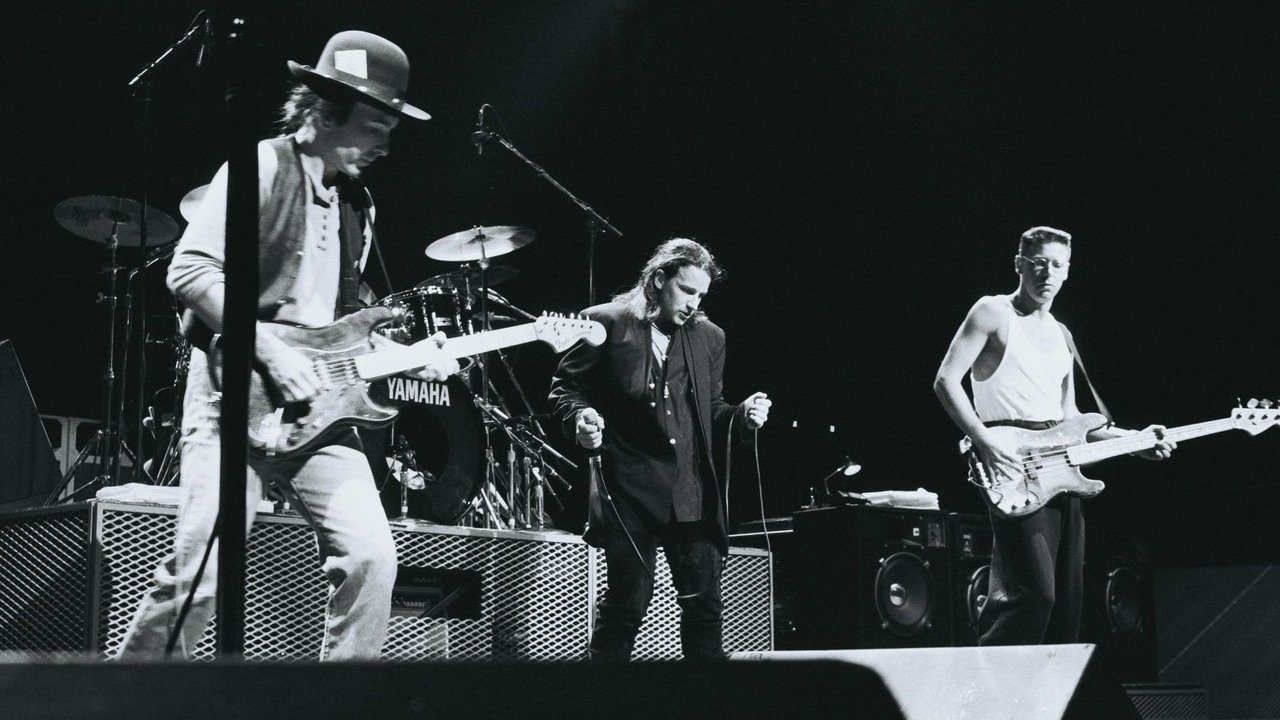

The film immediately strikes you with its visual dichotomy. Shot primarily during the triumphant, stadium-filling final leg of The Joshua Tree Tour, the concert footage is rendered in glorious, stark black and white by the legendary cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth (yes, the very same eye behind the rain-slicked gloom of Blade Runner (1982)). These sequences are pure spectacle. Bono, messianic and magnetic, holds court; The Edge coaxes that unmistakable, chiming stratosphere from his guitar; Adam Clayton and Larry Mullen Jr. provide the unwavering, powerful rhythmic core. Moments like "Where the Streets Have No Name" or a thunderous "Bullet the Blue Sky," captured with such stark grandeur, remind you exactly why U2 became the biggest band on the planet. The sheer energy radiating off the screen, even through the fuzzy warmth of remembered VHS tracking, is undeniable. Cronenweth's lensing elevates the stadium rock show into something almost mythical.

Interspersed with this monochrome majesty are colour documentary segments, tracking the band's journey across America as they delve into the roots of rock and roll – blues, gospel, country. It’s here the film becomes more complex, and occasionally, a little awkward. We see them visiting Graceland with a reverence bordering on the comical, jamming somewhat tentatively at Sun Studio in Memphis, and conducting slightly stilted interviews on the streets of Harlem. The intention is clear: to position U2 not just as rock stars, but as humble students paying homage to their musical forefathers. It's a noble goal, but the execution sometimes feels… studied.

Moments of Grace (and B.B. King)

Yet, within these colour segments lie some of the film's most genuinely affecting moments. The studio collaboration with the mighty B.B. King on "When Love Comes to Town" is an absolute highlight. There's a palpable sense of mutual respect, King’s effortless cool and soulful mastery providing a grounding counterpoint to Bono’s eager intensity. You see a band genuinely thrilled and slightly intimidated to be in the presence of a legend. Similarly, the sequence where U2 joins forces with the Harlem gospel choir, The New Voices of Freedom, for a soaring rendition of "I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For" possesses a raw, spiritual power that transcends any potential awkwardness. These moments feel earned, authentic connections amidst the larger-than-life tour machine.

Retro Fun Facts & Filming Feats

Bringing this dual-natured beast to life wasn't simple. Director Phil Joanou, then relatively young (he'd later give us the underrated crime drama State of Grace (1990)), was juggling a massive stadium tour production with intimate documentary filmmaking. Capturing Cronenweth's vision in those vast arenas required immense technical coordination, especially in an era before widespread digital assistance. The film was intrinsically tied to the double album of the same name, a mix of live recordings and new studio tracks exploring similar themes. This multimedia approach was ambitious, though it perhaps diluted the focus of both projects. Reportedly budgeted around $5 million, the film grossed a respectable, if not staggering, $8.6 million domestically – its cultural impact, however, arguably outweighed its box office haul, sparking endless debate about the band's direction. Critically, it was divisive; some lauded the music and scope, while others (famously, Rolling Stone magazine regarding the album) accused the band of hubris and overreach. Even the fleeting, slightly random appearance by Dennis Hopper reciting Kipling adds to the film's unique, sometimes bewildering, flavour.

The Sound and the Fury

Watching Rattle and Hum on VHS back in the day was an event. I remember the sheer volume we’d crank it up to, trying to replicate that stadium feel in the living room. The tape, often rented from the local store (likely nestled between Top Gun (1986) and Die Hard (1988)), felt substantial, important. It captured U2 at a fascinating crossroads – grappling with superstardom while consciously trying to reconnect with something more profound, more American.

Did they occasionally seem overly serious, even a touch self-important? Perhaps. Bono's earnest pronouncements could sometimes tip over the edge. But isn't that part of the charm, looking back? That willingness to wear their hearts, and their influences, so openly on their sleeves? It’s a vulnerability that feels distinctly of its time, before the ironic detachment of the 90s fully took hold (a shift U2 themselves would masterfully navigate with Achtung Baby in 1991, arguably as a direct reaction to the Rattle and Hum experience).

Final Reflection

Rattle and Hum isn't a perfect film. It’s uneven, occasionally awkward, and undeniably earnest. But it’s also visually striking, musically powerful (especially in the live segments), and captures a specific, fascinating moment in time for one of the world's biggest bands. It documents their ambitious, slightly flawed attempt to wrap their arms around the vastness of American music, and in doing so, reveals as much about their own identity at that peak moment as it does about blues or gospel. It’s a snapshot of sincerity and spectacle, wrestling with each other on screen.

Rating: 7/10

Justification: The score reflects the undeniable power of the live performances and the striking B&W cinematography, which elevate the film significantly. The collaborations, particularly with B.B. King, offer genuine highlights. However, it's docked points for the uneven documentary segments, which sometimes feel staged or awkward, and the overall sense of earnestness occasionally bordering on self-importance that prevents it from being a truly seamless or universally resonant piece like some other iconic concert films. It’s a fascinating, flawed, but ultimately rewarding document of its time.

Lasting Thought: What remains most potent about Rattle and Hum isn't just the music, but that feeling of a band reaching so high, exposing their searching and their influences so openly, even if they didn't quite grasp everything they were reaching for. A bold swing, even if it wasn't quite a home run.