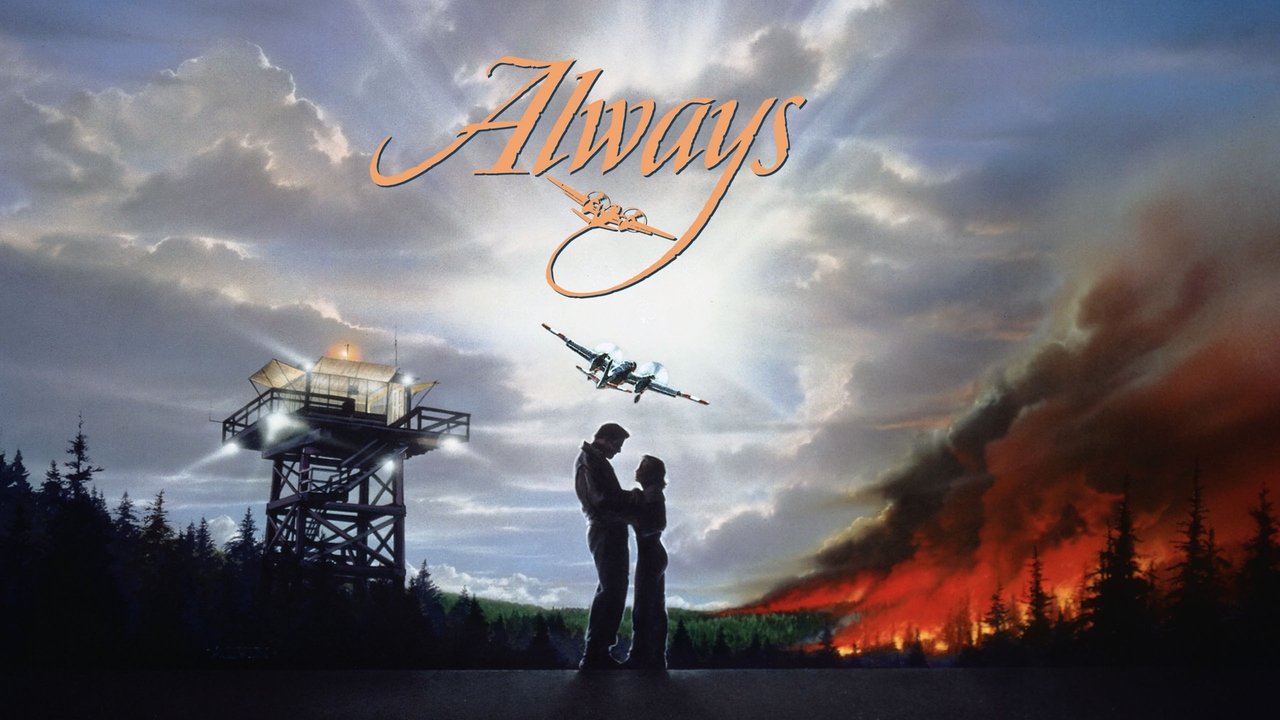

There’s a certain kind of light in a Steven Spielberg film, isn't there? Often it’s the otherworldly glow of discovery or the stark beam of adventure. But in Always (1989), it feels different – softer, more diffused, like sunlight filtering through smoke or the gentle radiance of memory. It's a film that stands apart in his 80s output, a deeply personal project that swaps spectacle for sincerity, trading edge-of-your-seat thrills for a more contemplative exploration of love, loss, and letting go. For many of us browsing the New Releases section back then, expecting another E.T. or Indiana Jones, it might have felt like a curveball.

Whispers on the Wind

At its heart, Always is a remake of the 1943 wartime romance A Guy Named Joe, a film Spielberg reportedly cherished since childhood. He transplants the story from WWII pilots to the rugged world of aerial firefighters in the American Northwest. Richard Dreyfuss, reteaming with Spielberg after Jaws (1975) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), plays Pete Sandich, a supremely skilled, risk-addicted pilot. He’s deeply in love with Dorinda Durston (Holly Hunter), an air traffic controller who lives in constant fear for his safety. His best friend, Al Yackey (John Goodman), provides grounded humor and loyalty. When Pete pushes his luck one time too many during a perilous rescue, he dies, only to return as a ghost, tasked with mentoring a new generation pilot, the earnest Ted Baker (Brad Johnson), and watching him fall for the still-grieving Dorinda.

It's a premise steeped in supernatural romance, a genre less common in the blockbuster landscape of the late 80s. There's an undeniable, almost old-fashioned sweetness to it, a willingness to wear its heart directly on its sleeve. Does it sometimes tip into overt sentimentality? Absolutely. Yet, there's a conviction behind it that feels genuine, largely thanks to the commitment of its cast.

Sparks in the Sky, Tears on the Ground

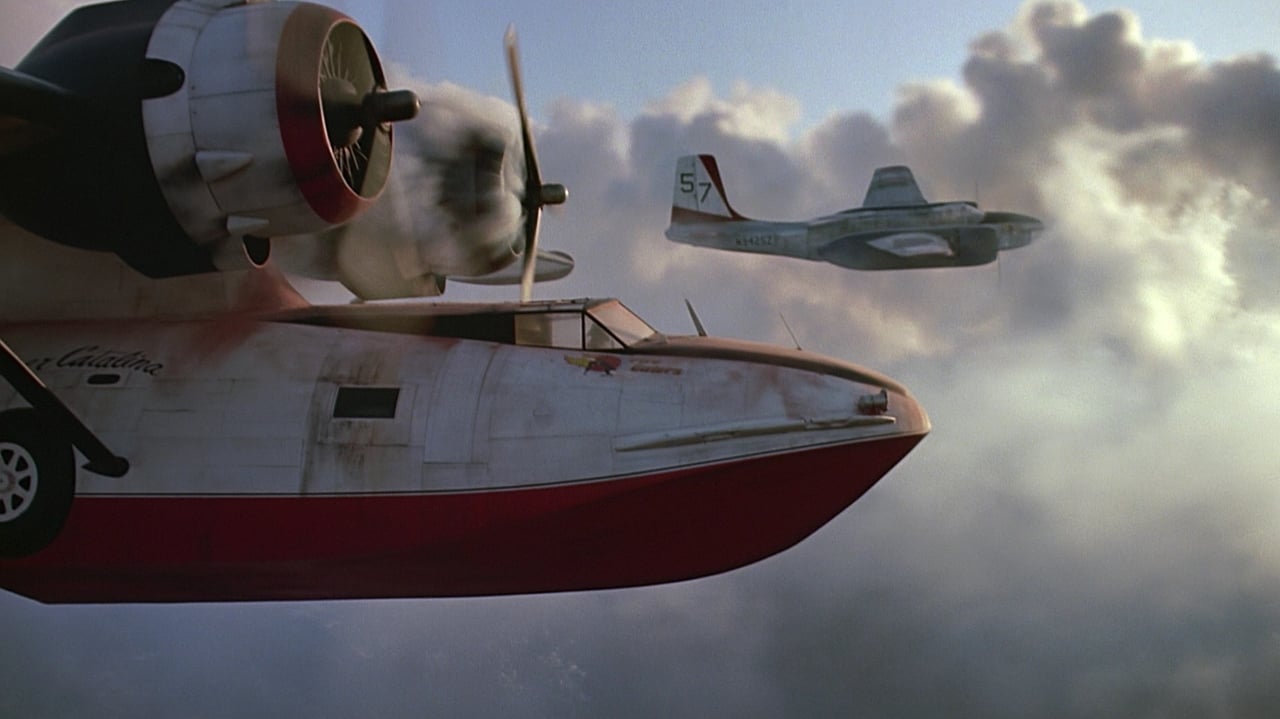

Spielberg brings his usual visual flair to the firefighting sequences. Even viewed today, decades past the cutting edge of practical effects, there's a tangible weight and danger to the scenes of planes swooping low through smoke-choked valleys, dumping retardant just feet above the flames. Reportedly, a mix of real aircraft (including WWII-era bombers converted for firefighting), intricate miniatures, and early digital compositing was used – a testament to the craft of the era. You feel the heat, the turbulence, the immense pressure these pilots operate under. It's a visceral counterpoint to the ethereal nature of Pete's ghostly existence.

The performances are the film's anchor. Richard Dreyfuss radiates effortless charm as Pete, making his reckless bravado understandable, even endearing. His transition to a spectral observer, filled with longing and regret, carries a quiet weight. It's his chemistry with Holly Hunter that truly sells the central relationship. Hunter is simply magnificent as Dorinda. She embodies fierce independence, palpable grief, and vulnerability, often all within the same scene. You believe her love for Pete, her devastation at his loss, and her hesitant steps towards finding happiness again. John Goodman, as ever, is a welcome presence, offering warmth and humor that prevents the film from becoming too maudlin. Brad Johnson has the slightly thankless task of being the 'other guy', but he brings a necessary sincerity to Ted.

A Final, Graceful Bow

And then there's Hap. In her final screen appearance, Audrey Hepburn graces the film with a luminous cameo as the angelic guide who explains Pete's new purpose. Filmed with a soft, almost halo-like glow, her presence lends the film an unexpected layer of gentle authority and grace. It’s a small role, but unforgettable. Apparently, she donated her entire salary for the film – reportedly $1 million – to UNICEF, a fact that only deepens the warmth of her appearance. It feels like a fitting, quiet farewell from a true screen legend.

Retro Fun Facts

Spielberg's desire to remake A Guy Named Joe was a long-held passion project. He dedicated Always to Victor Fleming, the director of the 1943 original. While critically met with mixed reviews and becoming one of Spielberg's less commercially successful films of the period (grossing around $74 million worldwide on a $31 million budget – respectable, but not the blockbuster numbers expected of him then), it found a comfortable afterlife on VHS. I remember renting it, perhaps drawn by the Spielberg name or the familiar face of Dreyfuss, and being surprised by its gentle pacing and emotional focus. It wasn't about aliens or artifacts; it was about the human heart. The score by John Williams, while perhaps less iconic than his adventure themes, perfectly captures the film's blend of melancholy and hope.

Lingering Embers

Always isn't a perfect film. Its pacing can feel leisurely, and the blend of high-stakes action and wistful romance doesn't always mesh seamlessly. The supernatural rules feel a bit convenient at times. Yet, revisiting it now, there's an undeniable sincerity that resonates. It asks questions about love's endurance, the pain of letting go, and the courage it takes to move forward after loss. Doesn't that process often feel like navigating through smoke, hoping for clear air ahead?

It feels like a film made from the heart, perhaps more for Spielberg himself than for the multiplex crowds of '89. It’s a reminder that even our biggest filmmakers sometimes need to tell quieter, more personal stories. It might not have set the box office ablaze, but it left a warm glow, a gentle ache, much like the memory of a cherished VCR favorite rediscovered decades later.

Rating: 7/10

Always earns its score through the sheer power of its performances, particularly Holly Hunter's deeply felt portrayal of grief and resilience, and the undeniable craft Spielberg brings even to quieter material. The aerial sequences remain impressive for their time, and Audrey Hepburn's final appearance adds a poignant touch. While its earnest sentimentality might feel dated to some and the pacing occasionally lags, the film’s emotional core remains surprisingly resonant.

It leaves you not with adrenaline, but with a quiet contemplation – a film less about the fire itself, and more about the light that remains after the flames die down.