Some monsters are born of radiation and rage. Others, it seems, are born of grief itself, twisted into nightmare shapes by science run amok. Godzilla vs. Biollante (1989) isn't just another entry in the King of the Monsters' long reign; it's a chilling detour into biological horror, a film that feels less like a typical kaiju brawl and more like a melancholy opera scored by atomic breath and snapping vines. Watching it again, even now, that unsettling feeling lingers – the unique dread sparked by its central, tragic antagonist.

A Monster Born of Sorrow

Emerging five years after the grim reboot The Return of Godzilla (1984), this installment plunged the Heisei era into even darker waters. The premise alone feels like something dredged from a fever dream: Geneticist Dr. Shiragami (Koji Takahashi), mourning his daughter Erika, fuses her cells with those of a rose. When an earthquake destroys his lab, he desperately attempts to preserve this hybrid life by splicing it with... Godzilla cells. Yes, those Godzilla cells, recovered after the '84 attack and now the object of intense corporate espionage and military maneuvering. What blooms from this unholy union isn't just a flower; it's Biollante, a creature that embodies a uniquely disturbing fusion of beauty and terror. Doesn't that initial giant rose form, silently floating on the lake, still possess an eerie, watchful quality that unsettles more than outright aggression?

The story behind the story is almost as strange. Toho actually ran a public story-writing contest to find the next Godzilla concept, seeking fresh ideas after the relatively straightforward previous film. The winner? Shinichirō Kobayashi, a dentist and sci-fi writer, whose concept of a grieving scientist creating a plant-based monster became the core of the film. Director Kazuki Ōmori (who would return for the following Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah in 1991) took this poignant seed and cultivated it into a film dense with intrigue, bio-ethical questions, and, of course, spectacular monster action.

The Terror Takes Root

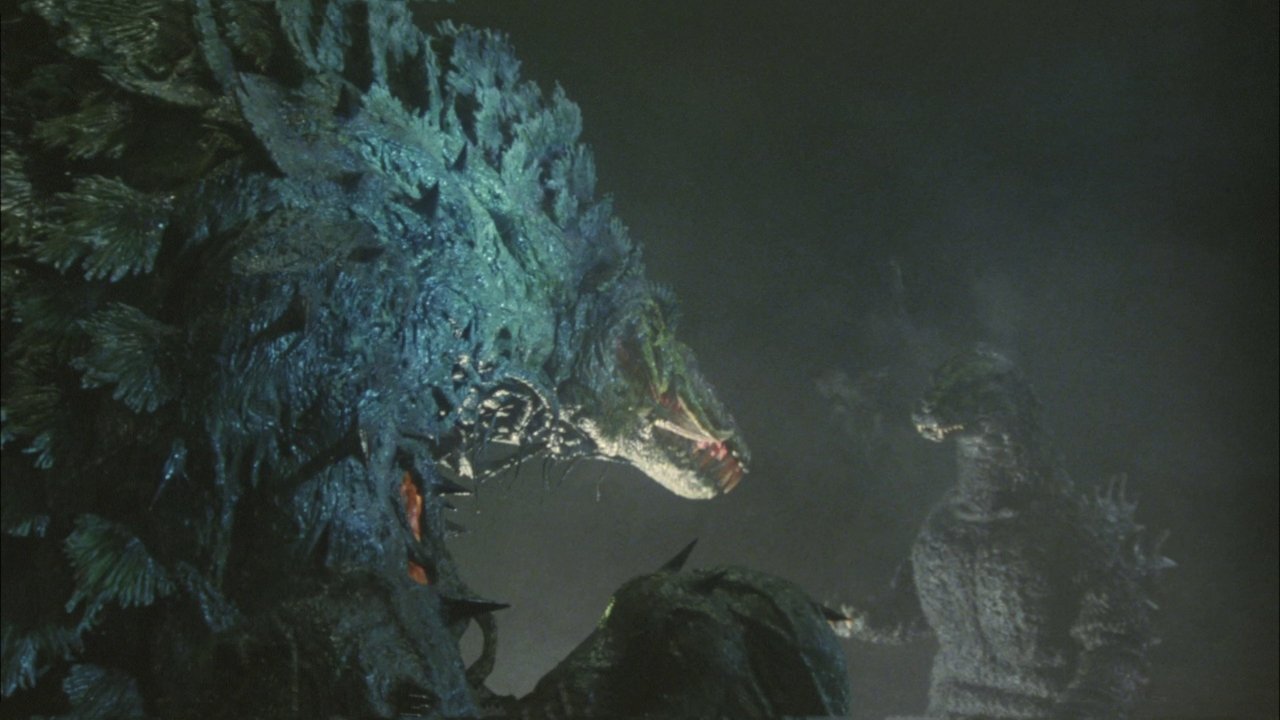

Let's be honest, Biollante steals the show. Her design progression is masterful. The initial, elegant Rose Biollante is hauntingly beautiful, hinting at the human soul trapped within. But when she later erupts into her final form – a hulking behemoth of snapping jaws, acidic sap, and writhing, vine-like tendrils – it's pure nightmare fuel. This wasn't CGI trickery; this was the pinnacle of late-80s practical effects artistry. The sheer scale and complexity of the Biollante prop were immense, reportedly requiring dozens of wires and a small army of puppeteers crammed beneath the miniature sets to bring its terrifying movements to life. The result is a creature that feels tangible, weighty, and genuinely organic in its monstrosity. It remains one of the most imaginative and disturbing foes Godzilla has ever faced. That visceral quality, the feeling that something truly unnatural was thrashing on screen, was potent on a flickering CRT back in the day.

Godzilla Amidst the Thorns

Godzilla himself, represented by the imposing "BioGoji" suit, is almost a secondary player in his own film, drawn into conflict first by the psychic call of Biollante (implied to share Erika's consciousness) and later by military intervention involving newly developed Anti-Nuclear Energy Bacteria. He remains a destructive force of nature, an embodiment of nuclear consequence, but here he feels less like the central villain and more like an inevitable storm colliding with a deeply personal tragedy. The battles between the two are highlights, particularly their final confrontation in Osaka, showcasing impressive pyrotechnics and miniature work that felt epic on a VHS tape.

The human element, involving corporate spies, Saradian agents (a fictional Middle Eastern country), and the Japanese Self-Defense Force, adds layers of complexity – perhaps, some argue, too many. Actors like Kunihiko Mitamura as Kazuhito Kirishima and Yoshiko Tanaka as Asuka Okouchi navigate the plot of stolen G-cells and bio-weapon anxieties. While sometimes feeling a touch convoluted, this espionage subplot grounds the fantastical elements in real-world (well, Cold War-era adjacent) concerns about genetic engineering and proliferation, themes that resonate differently but perhaps even more strongly today. Masanobu Takashima also makes his series debut here as the determined Major Kuroki, providing a familiar human face for later installments.

A Cult Bloom Despite a Frosty Reception

Interestingly, despite its creative ambition and stunning monster design, Godzilla vs. Biollante was considered a box office disappointment for Toho upon release in Japan. It earned roughly ¥1.04 billion (around $7 million USD at the time) against a budget estimated near $5 million. Perhaps audiences weren't quite ready for its somber tone, complex plot, and horror-inflected approach after the more straightforward disaster movie feel of the '84 film. Yet, time has been incredibly kind. It’s now widely regarded by fans as one of the best, most unique entries in the entire franchise, precisely because of its willingness to be different, darker, and more thoughtful. It’s a testament to how sometimes, the oddities we discovered tucked away on video store shelves become the films we treasure most. I distinctly remember renting this one, drawn by the bizarre cover art, and being completely captivated by how different it felt – less pure action, more strange, sad science fiction.

The score by Koichi Sugiyama (famous for his work on the Dragon Quest video game series) perfectly complements the mood, shifting from militaristic themes to haunting melodies that underscore Biollante's tragic existence. It lacks the iconic Akira Ifukube bombast but creates its own unique sonic identity for the film's specific blend of melancholy and menace.

Final Verdict

Godzilla vs. Biollante remains a fascinating, beautifully grotesque outlier in the kaiju genre. It dared to blend poignant tragedy with intricate monster design and bio-horror themes, creating something truly memorable. While the human plot can sometimes feel overly intricate, the sheer visual inventiveness, the palpable menace of Biollante's practical effects, and the film's surprisingly melancholic soul make it essential viewing. It proved Godzilla films could be more than just monster mashes; they could be haunting, strange, and unexpectedly moving.

Rating: 8.5/10

The score reflects its standing as a unique and ambitious entry, excelling in monster design, practical effects, and atmospheric tone, slightly tempered by a human plot that can feel a bit dense. It's a dark gem from the Heisei era, a film whose unsettling beauty and monstrous tragedy continue to resonate long after the VCR heads stopped spinning. Doesn't it feel like proof that sometimes, the most memorable monsters are the ones with a broken heart?